crafting_elastic_self_

advertisement

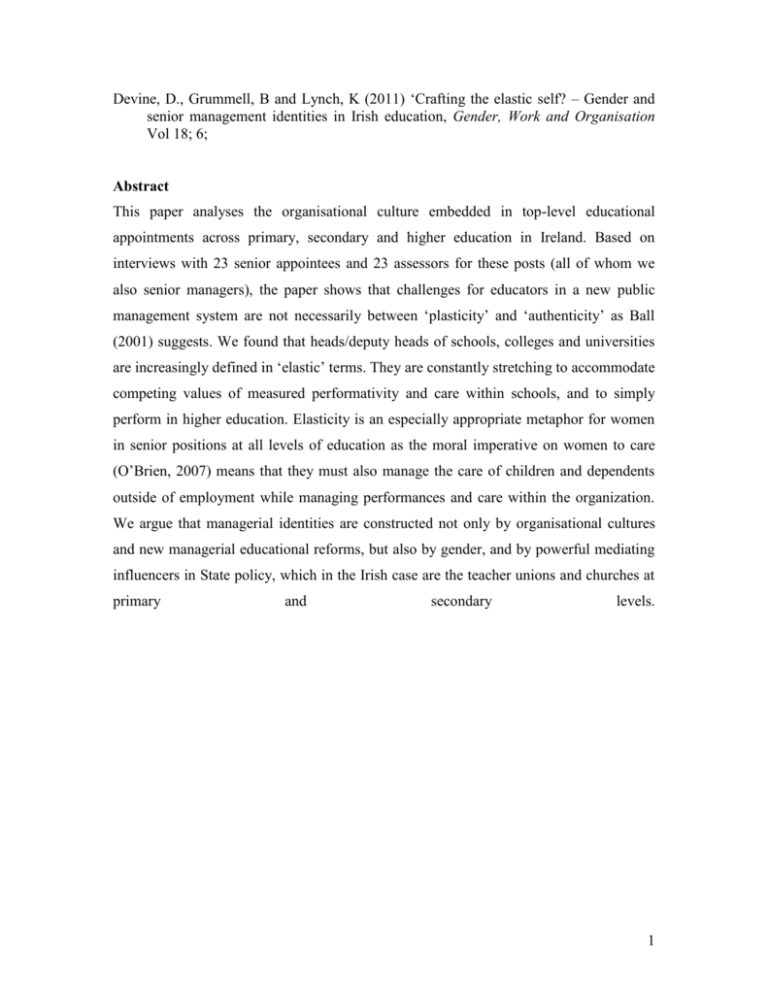

Devine, D., Grummell, B and Lynch, K (2011) ‘Crafting the elastic self? – Gender and senior management identities in Irish education, Gender, Work and Organisation Vol 18; 6; Abstract This paper analyses the organisational culture embedded in top-level educational appointments across primary, secondary and higher education in Ireland. Based on interviews with 23 senior appointees and 23 assessors for these posts (all of whom we also senior managers), the paper shows that challenges for educators in a new public management system are not necessarily between ‘plasticity’ and ‘authenticity’ as Ball (2001) suggests. We found that heads/deputy heads of schools, colleges and universities are increasingly defined in ‘elastic’ terms. They are constantly stretching to accommodate competing values of measured performativity and care within schools, and to simply perform in higher education. Elasticity is an especially appropriate metaphor for women in senior positions at all levels of education as the moral imperative on women to care (O’Brien, 2007) means that they must also manage the care of children and dependents outside of employment while managing performances and care within the organization. We argue that managerial identities are constructed not only by organisational cultures and new managerial educational reforms, but also by gender, and by powerful mediating influencers in State policy, which in the Irish case are the teacher unions and churches at primary and secondary levels. 1 Introduction: While teaching is a feminised profession, senior management appointments in education are disproportionately male, with the under-representation of women becoming more marked as one moves from primary to higher education (Blackmore 1999, Brooking 2003. Moreau et al 2007). A review of trends in Irish education (Grummell, Devine and Lynch, 2009, O’Connor, 2007) mirrors international patterns, showing declining numbers of women in senior management positions from primary to tertiary education. International research has also highlighted the gendered, and specifically masculinist nature of corporate organisational cultures and how these influence the recruitment and retention of women into senior management positions over long periods of time (Benschop and Brouns, 2003, Blackmore, 1999, Halford and Leonard 2001). Research on new managerial reforms shows that their impact on the culture of public sector organisations, including the education sector is not neutral (Apple, 2004; Farrell and Morris 2003, Davies et al 2006; Peters, 2005). Moreover, it has deeply gendered implications (Bailyn, 2003). There is a growing concern that new managerial reforms will exacerbate further gender inequality in senior management appointments. Using data from case studies of 23 top-level educational appointments in Ireland we show how senior management posts in education are increasingly guided by new managerial ideals of intense organisational dedication, long work hours, performativity and competition. We argue that this entails the crafting of an ‘elastic self’ by senior appointees,that is constantly stretched by the intensification and demands of the management role. However, new managerialism is neither gender neutral nor immune to mediation by powerful stakeholders in education. Our data shows how the experience of elasticity varies by educational sector, owing to the significant influence of powerful stakeholders in off-setting neo-liberal change; both trade unions and churches have played a powerful mediating role in the implementation of new managerial demands at primary and secondary levels but not in higher education. New managerialism is also mediated by gender and care identities, so women have to stretch more than men not only to manage the care of children and the performance outputs of their schools as men do, but also to manage the care of their own children and dependents outside of school. Being 2 the default carers in society puts an onus of care work on women that is morally impelled and inescapable if they are available to do it regardless of their class or status (Lynch et al., 2009). Women are also stretched by having to accommodate their management styles to organisational and management cultures that are characterised by hegemonic masculine norms (Connell 2000)i. While women are proportionately under-represented in senior management across all sectors of education, the more overt managerialism evident in the higher education sector, suggests that women, (and men who may be primary carers), will be even more under-represented in this and other sectors if new mangerialism takes hold. Gender and New Managerialism in the Education Sector – Crafting an elastic self? There is a cultural shift in educational organisations internationally, most especially those in the Anglo Saxon economies, toward the values and orientations of the market (Clarke et al 2000, Bonal 2003, Farrell and Morris 2003, Davies et al 2006). For those in the caring professions, market-oriented forms of new managerialism pose specific challenges because care itself is neither a quantifiable commodity nor an outcome that is open to strategic measurement, as shown by recent research into the health sector (Toynbee, 2007). In spite of the commitment to care that is central to the educator’s role (Noddings, 2004), within an increasingly managerialist system, educationalists struggle to retain this balance between their commitment to the broader goals of education, with the more narrowly defined goals of performativity and competition in the education marketplace (Ball 2003, Day et al 2005, Mahony et al 2004). Ball and others argue that educators have to retain an ‘authentic self’ built around the pursuit of good teaching, student learning, and the care for others this entails, and a more ‘plastic self’ that satisfies targets set by educational managers removed from the coal-face of teaching and research practice (Ball 2001, Thrupp and Willmott 2003, Court 2004). In this paper we suggest that conceptualising identity and self in dualist terms (as authentic/inauthentic vis-à-vis plastic) underplays the complex and contradictory processes involved in identity management, especially in organisations with a professional care remit. The struggle to manage competition and care under new managerial approaches to education, requires 3 rather the fashioning of an ‘elastic’ self that must expand and contract as the pressures to perform or to care shift organisationally. The experiences of identity construction and management differs across sectors of education however (Day et al 2006). Certain organisational cultures and leadership styles can offset the more negative and limiting aspects of new managerial reforms (Ball 1997, Court 2004, Day 2005, Gewirtz and Ball 2000, Gunter 2001). This happens because organisations are embedded in broader structures of power and control that derive from the historical positioning and influence of significant mediators in education, something that is often ignored in the analysis of educational change (Lynch, 1990). In Ireland, teachers are strongly unionised at primary and post-primary levels. They play a key role in negotiating educational change as do the Catholic church. Both the unions and the churches (of all denominations) have legally constituted powers to influence policy being named as educational partners in the Education Act, 1998. In the higher education sector however, such counter-resistant influences are not as evident. Power and control over universities and higher education institutions is legally constituted in the heads of colleges. Although there is relatively strong unionisation in higher education, there is neither the scope nor capability to exercise influence over policy that unions exercise at primary and secondary levels. Thus the pressure to conform to the norms of new managerialism are not exercised evenly across educational sectors. Managing the emotional work that is involved in negotiating the tensions that arise within managerialist cultures would appear to apply to both men and women in the senior management role. However, as senior managers are gendered subjects, it is important to ask if and how gender impacts on the experience of elasticity. Given the predominance of women in caring (Pettinger et al., 2006), the moral imperative on women to do care work (O’Brien, 2007), and the intense organisational dedication and time commitment required in ‘greedy organisations’ characterised by new managerial reforms (Currie et al 2000, Davies 2006, Collinson 2003), it would appear that women face unique challenges combining their paid work and personal lives (Acker 1999, Coleman 2001, Lyon and Woodward 2004, Folbre 2004, Mahony et al 2004). The stretching and emotional 4 investment of self that is required to balance care and performance in school or college is exacerbated by the demands of primary caring outside of employment. Women who do enter senior management often forfeit having children and/or take longer than their male counterparts to achieve promotion (Acker and Dillabough 2007, Blackmore 2004, Bagihole 2002). Furthermore, women who enter managerial positions in organisations where men traditionally manage, must also operate within a masculinised organisational culture. They are the organisational ‘other’ and must manage their otherness or not succeed (Halford and Leonard, 2001, Probert, 2005). An additional stretching of self is required as they invest effort in managing their ‘other’ status - ‘doing’ gender in a manner which aligns more to the norms of the existing management culture. Research consistently highlights the tension this creates for women in attempting to minimise their gender difference in order to be treated equally to men, while at the same time retaining a distinct ‘feminine’ identity so as not to be ridiculed for appearing overly ‘masculine’ (Reay and Ball 2000, Ozga and Deem 2000, Halford and Leonard 2001, Bailyn 2003). Our data suggest that the challenge of new managerialism in a care-driven profession like education is not always between authenticity and plasticity as Ball (2001) has suggested. It is about elasticity, as both female and male managers have to attend to the care function of education as well as performance management when socio-political values place a strong emphasis on care. The metaphor of elasticity applies especially to women mangers as they are bound by the moral imperative to be the primary family carers. Women are stretched too by having to manage their feminine identities within maledefined work senior management positions. The study in context: Ireland is not unlike many other EU countries in that the % of women in senior management positions declines steadily as one moves from primary to higher education (O’Connor, 2007). While 50% of primary schools heads and 25% of second-level heads of schools are women, none of the heads of the seven universities are women and only 5 three of the 15 heads of Institutes of Technology are women. It is in this context that we undertook a study of the culture of senior appointments, both a study of the values of those who assessed and appointed heads and those appointed to senior management roles as heads or deputy heads of schools, colleges and universities. The research upon which this paper is based involved case studies of appointment of 23 senior managers across the education sector. The case studies sought to identify the cultural codes enshrined in both the process and experience of appointment, as well as the appointees experience in post. Each case study consisted of an in-depth qualitative interview with the recently appointed educational manager (school principal/head teacher in the case of primary and second-level schools), an interview with one or more assessors from the interview board (46 interviews in total), each of whom had considerable experience themselves of management within the education system, and documentary analysis. The three sectors of Irish education were represented in the 23 case studies, including 8 primary and 8 second level schools (co-ed and single sex across a variety of urban and rural geographical areas, socio-economic backgrounds and school sizes), and 7 higher education institutions (universities, institutes of technology, further education colleges and a statutory educational agency). An equal gender balance of candidates was achieved with the exception at higher education where 3 male and 4 female appointees were interviewed. Analysis of the completed case studies was completed to identify key findings from the interview data using an open coding system and MAXqda computer software. Crafting the elastic self? Management and identity in an era of educational change Senior appointees spoke at length about their experiences in their new posts, providing a detailed overview of the work of educational leaders in the Irish Education System. They described how a discourse of accountability and performativity increasingly permeated many areas of educational management, that was itself underpinned by extensive leglislative and policy change: 6 There’s the Welfare Act, the Education Act itself, Special Needs now is the other big one that people are talking about, the pile of stuff has gone bigger (Male, Principal Second level Scoil Nephin) The new requirements under the 1997 Act which delineate a form of management that is alien if you like to the traditional notion of a University. (Female assessor Higher Education Institution Inis Mheáin) Change was experienced differently across the educational sectors however. For those in the school sector, the new managerial culture was experienced primarily through the intensification of bureaucratic demands (form filling, doing applications for funding and development planning, and responding to Department of Education and Science (DES) queries) often without the appropriate administrative back up to support the change: So you have the new curriculum, you’ve got legislation, you’ve got special needs, you’ve got health and safety, all of these things becoming more and more important. And each time a new measure or something new is introduced, the one person that it impacts upon by increasing workload is the principal (Male assessor, co-ed primary, Scoil Derg) Senior post holders in the primary sector described the huge demands in terms of their personal self and time. Most school principals worked very long days, and those who did not stay on late after school, tended to do their administrative work late in the evenings at home, or at the weekend. Niamh, the principal of Scoil Comeragh, a second-level school, described ‘time commitment and responsibility’ as one of the biggest personal challenges that faced senior managers in schools as they attempted to manage the mounting scale of work. Her views were shared by others: The Department of Education and Science are so overburdening the principal with reports, with compliance, that the principal doesn’t get a chance to have time to just nurture their own sense of what the school should be about (Male assessor, second level, Scoil Sperrin) It’s a hell of a job, I mean principalship. I did it for five years, I did nothing else. I didn’t eat a lunch – I worked night and day at it! (Male Assessor, Second-Level, Scoil Mourne) 7 What is evident from the interviewees’ comments is that their management responsibilities required them to stretch themselves significantly. Emotions of guilt and depression, feeling overburdened and swamped sat alongside the energy and buzz these senior appointees experienced in their roles – as they ‘managed their insides’ (Alvesson and Willmot 2002), seeking to exercise a form of ‘Super leadership’ in the satisfaction of the diversity of demands upon them. It is tiring and it is wearing and there are days you’d love to say ‘I wish you knew what I was going through’ but you can’t and you get on with it’ (Female principal, Second level, Scoil Mourne) The research findings confirmed a sense of dedication and vocation in the narratives of school principals (Sugrue 2004), with vision, ethos and care of both staff, students and service to the wider community at the heart of their work, in spite of the multi-faceted demands that increasing managerialism placed upon them: My philosophy is quite easy, it starts with the child in the classroom and it ends with the child in the classroom. I would aspire to provide the best possible education for those (Male Principal, primary, Scoil Derravaragh) Recently appointed Senior managers in the Third level/Statutory sector appeared much less conflicted about their roles. Their decision to apply for these senior management positions in most cases reflected almost an internalisation and acceptance of managerialism into their constructs of manager identity. Managerialism was talked about generally as inevitable in an increasingly competitive national and international environment and essential to the modernisation and survival of each higher education institution: What I think we have needed to do as a sector is to create higher levels of strategic efficiency. But we were a university system that developed on a totally opportunistic basis. And that, in international benchmarking terms was not sustainable (Male Assessor, InisMhean Higher Education Institution) 8 I don’t feel I am terribly conflicted that there is any clash between that [budgetary/managerial role] and people’s academic freedom or integrity at all (Female senior appointee Rathlin higher Education Institution) While interviewees in this sector were also concerned about issues related to student experience and welfare, the tensions between a discourse of care versus management was not as strong in their narratives. More prevalent were tensions in managing the time-bind between their administrative responsibilities and the demand for publishing, research funding and developing a competitive edge in new fields. In this sense it was clear that the organisational culture within which they worked was one where performativity was more readily individualised to the person (Rose 2001) with the accompanying rewards that this incurred: We have our research information system so suddenly it is the people who are obviously deserving who are the ones who are being recognised. And for the others there is a clear route to recognition.(Male senior appointee, InisMhean higher Education institution) Coping with this changed culture gave rise to a time commitment to work which was experienced by senior appointees in the Higher Education Sector as ‘without boundaries’: To be quite honest, I’d say on average I work an 85 hour week… most of us at the level I am at, it’s just work, there is nothing else in our lives (Female Senior post holder at Colaiste Rathlin Higher Education institution) I mean in the depths of winter when we are working 12 hours days and nights I can become an incredibly dull person to be around…work in a management post takes up a lot of time…And that is what they pay you for (Female senior post holder at Saltees higher education institution) 9 In all sectors, the capacity to cope with the challenges of on-going and rapid educational change is suggestive of an elastic self, that is continually stretched with the intensification of the management role. For those in the school sectors this ‘elasticity’ derived from the desire to maintain a pastoral/care dimension to their role, in a context of an increasingly diverse student population, under-funding and absence of sufficient administrative support amid persistent compliance and bureaucratic demands from the Department of Education and Science. Within the higher education sector, elasticity derived from the need to manage individual research/publications output while moving the institution forward strategically in a competitive market-place and the unbounded commitment that was required in order to realise institutional goals. While there was also evidence of an emerging competitiveness in the school sector that derived from increasing media attention on school performance and competition among middle class parents (Lynch and Moran 2006), performativity was not ingrained into the identities of the senior appointees. This must be considered in light not only of the successful collective organisation of the Teacher Unions to resist overt forms of comparison between schools including league tables, but also the influence of religious management bodies to off-set overly commercialised approaches to schooling. Such collective resistance was not as evident in the higher education sector, giving rise to an implicit, and at times, explicit, acceptance about the inevitability of new managerial reform among most senior mangers at this level. Doing Gender and Senior Management in Irish Education Each of the women interviewed for this research had reached senior management level, yet clear differences emerged between their narratives and those of their equally successful male colleagues with respect to the impact of gender on their management identities. All female interviewees made reference to the significance of caring work and the raising of children as a key factor mediating women’s experience of career progression, while no male interviewee mentioned it as a significant factor for men as a group. That women were the primary carers of children was a core assumption of a number of assessors and principals, both male and female: 10 Why would any sane woman in her 30’s or 40’s with a happy family life, with a successful career in the classroom, abandon it to go into the trenches of administration and management, with all that it brings (Male Assessor, second level, Scoil Galtees) She [friend] was a principal and told me I was mad and ‘what on earth did I want to do principalship for’ and ‘what are you doing and don’t you have a young child?’ and things about time etc. (Female senior appointee, primary, scoil sheelin) It was assumed however that the decision to opt into/ or out of senior management was a lifestyle, and indeed moral, choice that derived from women’s ‘natural’ role as mothers and carers. It was not seen as a proscribed gendered choice arising from the way the senior management role was itself constructed: Women are at a later state in their careers [when they apply for promotion] generally, and that is their decision and that probably makes sense to them and probably it is sensible (Male assessor, primary, Scoil Allen) I think a lot of women are simply determining their work/life balance and particularly their child rearing responsibilities would be absolutely constrained by being appointed to a more senior post. (Female assessor Valentia Higher Education Institution) In such situations a dichotomy between family/care and promotion was clearly part of the discourse, ensuring that for women who did combine both, considerable ‘stretching’ was required in order to satisfy the demands of their dual roles: The last couple of nights [for example] I’ve brought work home with me and when the kids are gone to bed I can work on some of the paper work…and I might come in on a Saturday or Sunday if there is stuff that has to go into the Department on time or people don’t get paid (Female senior appointee Nephin second level school) Una in Rathlin Higher Education institution, made an explicit choice that she would not have any more children given the potential negative impact on her career: 11 It was a big influence in my only having one [child]… I made a conscious decision that I couldn’t get tenure and be pregnant and have a second child. And perhaps there is some naivety about the impact having children has on their [female colleagues] careers and where it keeps them (Una, Female Senior Appointee Rathlin Higher Education Institution). While there were also men with young children in the study, they were generally positioned as secondary carers and issues around child care were not part of the mind maps of male interviewees. The extent to which women felt they could combine their caring roles with professional commitments differed across the sectors however suggesting there was also a gendered aspect to organisational cultures across the sectors themselves that gave rise to differing modes of ‘dong gender’ within them. Managing the ‘other’ - gender and organisational culture in education While the difficulty of combining child care with senior management responsibilities was alluded to across all sectors, it was defined as least problematic in the primary sector especially by women, and to a slightly greater degree in the second-level sector: I think teaching is an area where women feel they can manage the dual tasks very well because they can juggle the hours and the time that they are working, and it has always been a good job for women (female assessor Nephin primary school) There are loads of women who have children and who are principals and it works out fine…you need to have a very good back up system…a husband who would do that [stay home a lot] (Female senior appointee second-level, Scoil Comeragh) In higher education combining child care with senior management was deemed especially problematic, as it ran counter to organisational cultures where performativity and intense organisational commitment was embedded in the senior management role. Speaking of doing job sharing as a way of managing child care, one assessor said: 12 The higher you go the reality is that the options are much starker. If you take jobs at my level, it would be well nigh impossible to job share or work a two or three day week. You are lucky to only get a five day week (Male Assessor, Saltees Higher Education Institution) There was a belief that total dedication to the job was essential at senior levels. This was made clear to a female applicant to a senior post by an interviewee who sat on many selection boards and who was himself in a senior position: The candidate we chose was a woman [but] she said that she wouldn’t be able to devote all her time to the teaching and research as I wanted, so in the end she chose not to join the Department (Male senior appointee InisMhean Higher Education institution). Such comments highlight the more explicit impact of new managerial cultures on both the life-choices (e.g. having a child or not, taking a career-break or not) and life-chances of women in the higher education sector, and of the additional stretching that is required of those who have caring responsibilities in order to realise their career potential. As one moved up the education sectors a more masculinised organisational culture was evident, especially in the narratives of interviewees in the higher education sector and to some extent in the post-primary (vocational) school sector: The VEC [vocational schools] would be far more masculine than the secondary schools’ (Female senior appointee, second level, Scoil Comeragh) The institution was remarkably male dominated, the senior management team, all seven of those were male (Senior Post Holder, Higher Education Institituion Inisbofin) Within the higher education sector the management of gender identity appeared to be an important element of ‘doing’ management among female interviewees. Their narratives outlined the tension they experienced in straddling dominant norms in relation to the ‘feminine’ while asserting their right to be taken seriously within their organisations by repressing the ‘feminine’ in favour of more masculinised modes of crafted self: 13 Women are afraid that if they take on a senior role they will lose their qualifications as a female…a lot of women have that: ’if I become the boss I won’t be attractive, I won’t be a good girlfriend, other women won’t like me, senior women can be so mean’. So there is an identity thing there for women (Female senior appointee Higher Education Institution, Rathlin) While academic title was an important indicator of status in the third level sector, this interviewee also commented upon the embodiment of status through styles of dress and demeanour that underplayed her more ‘feminine’ side: One of the benefits of being older and greyer is that you do get taken more seriously than when you are younger and slimmer and attractive and all of that.. you are either attractive or serious…sadly that is my experience (Female Senior Appointee, Higher Education institution, Rathlin) Within the more competitive and performative environment of this sector, a number of female interviewees also talked about their need to be ‘savvy’ in managing their femaleness, downplaying a stereotypical nurturing, motherly role, as well as being careful about the time invested in ‘lesser status’ caring work (Acker 1995, Blackmore and Sachs 2000): People have expectations for women in power that they would never have of men in terms of how nice you are to them…same thing among lecturers and students…female lecturer is not there she is perceived as not available, male lecture is not there he is busy… I have to be careful I don’t do all the ‘busy’ work…And frankly if you refuse you are often perceived as being difficult. But that is a minefield that I still is there for us [women]. (Female, Senior Appointee, Higher education institution:Valentia) I don’t go for the deferential ‘yes Minister’ kind of approach. I am a very political animal, you have to be to operate in this arena (Female Senior appointee, Higher Education institution: Saltees). For senior women ‘doing’ management involved coping with feelings of isolation/loneliness on a senior management team. In the higher education sector, women noted that sources of support and information were often difficult for the new female 14 appointees to access. The toughness that was required in being a senior manager in a male dominated management sector was also noted, reinforcing a sense of isolation from former female colleagues. The image of senior manager as tough and masculine acted as a potential deterrent to many women to apply for such positions: You get very tough in the game and I know from talking to my female colleagues they are quite determined they are not going there.You immediately become the enemy…and I read Machiavelli’s Prince and I’m utterly convinced by what it says (Female Assessor Higher Education, Inis Mheáin) However, while these female senior appointees were aware of their ‘otherness’ within the Higher Education organisation, this did not imply that they felt they were discriminated against, overtly at any rate. Their responses to any experiences of sexism were in the main ambivalent, minimised as unintentional sexism: Some older male comments have been a sort of humane sexism that is sort of understandable (Female Senior Higher Education Post Holder of Saltees) I felt under serious pressure from the maternity leave when I came back. I didn’t feel I could tell them that I was breastfeeding … this wasn’t bias or anything, it’s just that they had never faced this, they must have thought that they had got a mad woman… I mean I totally understand. (Female Senior Appointee in Higher Education Valentia) While Una in Colaiste Rathlin felt she experienced discrimination in the allocation of her professorship, she chose not to make an issue of this, in spite of her discomfort at her positioning in comparison to her male peers: I did feel uncomfortable when I realised that I was the only female senior appointee [at this level] who wasn’t professor…had I been more savvy I should have asked for it. So that is the only time when my sex probably stood against me (Female senior appointee, higher education institution Rathlin) 15 Not all interviewees agreed that the organisational culture in the higher and statutory sectors could be defined as ‘masculinist’, arguing that gender differences arose for historical reasons rather than any undue bias in the system presently: I don’t think it is so much that there is a macho culture at senior levels, I wouldn’t actually honestly think that (Female Senior appointee, Higher Eduation institution, Saltees) In past times it was much more difficult [for women], I think today it is maybe a bit easier. (Male Senior appointee, Higher Education Institution, Inis mheain) However this is where the issue of how the management role is constructed becomes crucially important – especially with respect to the attractiveness of management positions for those who do not conform to the dominant cultural and gendered organisational norms. The question arises if these norms preclude those with caring responsibilities, and women, in particular from taking up senior management positions? I cannot see any immediate change in the balance between males and females in senior positions in education because women are more inclined to look at the overall life situation. On most of the boards I have been involved in for senior University positions there simply have been no female applicants. Some progress has been made in Primary and Secondary Schools by encouraging women to apply and having networks of women and so on. But it hasn’t come to that yet in the University sector.(Female Assessor, Higher education institiution, Inis Mhean) Of particular concern is the assumption that new managerialism represents a meritocratic ideal, allowing those with the greatest drive and entrepreneurialism to ‘rise to the top’. While a delayering of management structures often typifies new managerial reforms, and this appears to undermine traditional patterns of male dominance (Collinson and Hearne 2003), the simultaneous construction of the manager role as a form of superleader, devoid of personal and care responsibilites ensures that in practice, new managerialism is far from gender neutral. In universities…the fact that most promotion now prioritises research means 16 that it is very difficult for women to devote the amount of time that seems to be necessitated by producing research and publications…I really think that society needs to remodel how it looks at work. (Female senior appointee, Higher education institution, Valentia). Concluding discussion Ball (2001) suggests that educators are expected to choose between an authentic and plastic identity in the construction of self in new managerial times. Our data suggests that the choice is not always that polarised. For a variety of politically and culturally specific reasons, elasticity is what is most often practiced by senior educational managers. Women are expected to be especially elastic in managing the multiple and competing demands that are placed on them not only as managers but also as primary carers. Ireland has been exposed to new managerial reforms in education similar to those in other countries (Lynch, 2006). While wide-ranging legislative and policy reform has led to intensification in the work of all senior appointees and the crafting of an ‘elastic self’, we found that the nature of this stretching was mediated by cultural/organisational differences across the sectors, as well as by gender. In the school sector, the absence of sufficient administrative back up and clear demarcation of management roles gave rise to senior appointees feeling ‘squeezed’ in a ‘catch all’ position that required them to continually work outside traditional school hours. Owing to the significant mediating role of both the Teacher Unions and the Churches in mediating neo-liberal change, however, the more competitive and performative elements of manager identity were not as prevalent in the identities of senior appointees at this level. In higher education a more pronounced emphasis on performativity was evident with the experience of being stretched deriving also from the focus on strategic planning and change. A gendered difference was also noted however not only in the general discourse around the suitability of senior management positions for women with caring responsibilities (and by implication the construction of the idealised manager as one unencumbered by care responsibilities), but also around the identity work that women had to do in order to work on equal terms with their male colleagues especially in higher education. The ‘Superleadership’ and stretching of self that is reinforced under new managerialism, in 17 terms of intense organisational dedication and commitment to the management role, provides an additional layer of work for women, who already have to manage their ‘otherness’ in organisations that have a more distinctive masculinised ethos. Learning to be ‘savvy’, managing one’s identity in order to be taken seriously, as well as overcoming the isolation in being ‘other’, was part of the repertoire of identity work of female senior appointees in the higher educational sector especially. Such patterns it is argued are becoming more, rather than less embedded under new managerial reforms, ensuring that it is those with caring responsibilities, most likely women, who are least likely to consider putting themselves forward for such positions. References: Acker, S. (1995) Carry on caring: the work of women teachers, British Journal of Sociology of Education 16(1), 21-36. Acker, S (1999) The Realities of Teacher’s work: Never a dull moment, London, Cassell Acker, S. and J. Dillabough (2007) Women ‘learning to labour’ in the ‘male emporium’: exploring gendered work in teacher education, Gender and Education, 19(3), 297316. Alvesson, M and Willmott, H (2002) Identity Regulation as Organizational Control – Producing the appropriate individual’, in Journal of Management studies, Vol 39, 619-644 Apple, M. (2004) ‘Creating Difference: Neo-liberalism, Neo-Conservatism and the Politics of Educational Reform’ Educational Theory, Vol 18, 1: 1244 Bagilhole, B (2002) Challenging Equal Opportunities: changing and adapting male hegemony in academia, British Journal of Sociology of Education, vol 23, No 1, 19 – 33 Bailyn, L. (2003) Academic careers and gender equity: lessons learned from MIT, Gender Work & Organization, 10(2) 137-153. Ball, S. J. (2001). Performativities and fabrications in education and economy: towards the performative society. The Performing School. D. G. a. C. H. (eds). London, Routledge Falmer. Ball, S.. (2003) ‘The Teacher’s Soul and the Terrors of Performativity’, Journal of Education Policy, Vol. 18, No. 2: 215-228. Benschop, Y. and Brouns, M. (2003) ‘Crumbling Ivory Towers: Academic Organizing and its Gender Effects’ Gender, Work and Organization, 10 (2), 194-212. Blackmore, J. (1999) Troubling women: feminism, leadership and educational change (Buckingham, Open University Press). 18 Blackmore, J (2004) Quality assurance rather than quality improvement in higher education? British journal of sociology of education, Vol 25, No 3: 383 – 394 Blackmore, J. and Sachs, J (2000) Paradoxes of leadership and management in higher education in times of change, International Journal of Leadership in Education, 3(1) 1-16. Bonal, X. (2003) The neoliberal educational agenda and the legitimation crisis: old and new state strategies, British Journal of Sociology of Education 24(2), 159-175. Brooking, K. Collins, G. Court, M. and J. O'Neill (2003) Getting below the surface of the principal recruitment 'crisis' in New Zealand primary schools, Australian Journal of Education 47(2), 146-159. Clarke, J., Gerwitz, S and McLaughlin, E. (2000) (eds) New Managerialism: New Welfare? London, Sage Collinson, D. L. (2003) Identities and Insecurities: Selves at Work Organization 10 (3): 527-547. Connell, R.W. (2000) The Men and the Boys. Sydney: Allen and Unwin. Coleman, M (2001) Achievement Against the Odds: the female secondary headteachers in England and Wales, School Leadership and Management, vol 21, No 1: 75 - 100 Court, M (2004) Talking Back to New Public Management Versions of Accountability in Education Educational Management Administration & Leadership Vol. 32 (2), 171-194 Currie, J. Harris, P. and Thiele, B. (2000) Sacrifices in greedy universities: are they gendered? Gender and Education 12(3), 269-291. Davies, B. Gottsche, M. and P. Bansel (2006) The rise and fall of the neoliberal university, European Journal of Education, 41(2), 305-319. Day, C (2005) Principals who sustain success: Making a difference in schools in challenging circumstances, International Journal of Leadership in Education, Vol 8, 4, 273-290 Day, C. K., Alison; Stobart, Gordan and P Sammons (2006). The personal and professional selves of teachers: stable and unstable identities British Educational Research Journal 32(4): 601 - 616. Deem, R. (2003) Gender, organizational cultures and the practices of manager academics in UK universities, Gender Work and Organization, 10 (2), 239-259. Ducklin, A. and J. Ozga (2007) Gender and management in further education in Scotland: an agenda for research, Gender and Education, 19 (5), 627-646. Farrell, C. M. and J. Morris (2003). The Neo-Bureaucratic State: Professionals, Managers and Professional Managers in Schools, General Practices and Social Work Organization - Interdisciplinary Journal of Organization theory and Society 10 (1): 129.- 146 Folbre, N. (2004) ‘A Theory of the Misallocation of Time’, in Folbre, N. and Bittman, M. (eds) Family Time: The Social Organization of Care, London: Routledge, 7-25. Gewirtz, S and Ball, S (2000) From ‘Welfarism ‘ to ‘New Managerialism’ : shifting discourses of school headship in the education marketplace, Discourse: studies in the cultural politics of education, Vol 21, 3, 253 - 268 Grummell, B. Devine, D. and K. Lynch (2009) Appointing senior managers in education: homosociability, local logics and authenticity in the selection process, Educational Management Administration and Leadership, (forthcoming). 19 Gunter, H (2001) Leaders and leadership in education, London, Paul Chapman Halford, S. and P. Leonard (2001). Gender, Power and Organisations. New York, Palgrave. Lynch, K. (1990) ‘Reproduction: the role of cultural factors and educational mediators’, British Journal of Sociology of Education, Vol.11, No. 1, pp. 3-20. Lynch, K. (2006) Neo-liberalism and marketisation: the implications for higher education, European Educational Research Journal, 5(1), 1-17. Lynch, K. and Moran, M. (2006) Markets, schools and the convertibility of economic capital: the complex dynamics of class choice, British Journal of Sociology of Education, 27(2), 221-235. Lynch, K., Baker, J. and Lyons, M. (2009) Affective Equality: Who Cares? London: Palgrave Macmillan. Lynch, K. Grummell, B. Devine, D. and M. Lyons (2006) Senior appointments in education: a study of management culture and its gender implications (Dublin, Gender Equality Unit, Department of Education and Science). Lyon, D. and A. E. Woodward (2004) Gender and Time at the Top: Cultural Constructions of Time in High-Level Careers and Homes The European Journal of Women’s Studies 11 (2): 205-221. Mahony, P. Hextall, I. and Menter, I (2004) Threshold assessment and performance management: modernizing or masculinising teaching?, Gender and Education, 16 (2) Moreau, M. Osgood, J. and A. Halsall (2007) Making sense of the glass ceiling in schools: an exploration of women teachers' discourses, Gender and Education, 19(2), 237-253. Noddings, Nell (2004) ‘Identifying and Responding to Needs in Education’, Cambridge Journal of Education, Vol 35, No. 2: 147-159. O'Brien, M. (2007) Mothers' emotional care work in education and its moral imperative, Gender and Education 19(2), 159-177. O'Brien, M. (2008) Gendered capital: emotional capital and mothers' care work in education, British Journal of Sociology of Education 29(2), 137-148 O'Connor, P. (2007) ‘The elephant in the corner: gender and policies related to higher education’, paper presented at Conference on Women in Higher Education, Queens University Belfast, April 19th-20th 2007 . Ozga, J. and Deem, R. (2000) Carrying the burdens of transformation: the experience of women managers in the UK, higher and further education, Discourse 21(2), 141153. Peters, M. (2005) ‘The New Prudentialism in Education: Actuarial Rationality and the Entrepreneurial Self’ Educational Theory, Vol. 55, No.2: 123-137. Pettinger, L., Parry, J., Taylor, R. and Gluckmann, M. (eds) (2006) A new sociology of work? (Oxford, Basil Blackwell). Probert, B. (2005) ‘I Just Didn’t Fit in: Gender and Unequal Outcomes in Academic Careers’ Gender, Work and Organization, 12 (1) 50-72. Reay, D and Ball, S (2000) Essentials of Female Management : Women’s ways of working in the education Market Place? Educational Management and Administration, Vol 28 (2), 145 - 159 Rose, N (2001) Governing the Soul, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press 20 Sugrue, C. (2004) Curriculum and ideology: Irish experiences, international perspectives (Dublin, Liffey Press). Taylor, J., (2001) The impact of performance indicators on the work of university academics: evidence from Australian universities, Higher Education Quarterly, 55(1), 42-61. Thrupp, M. and R. Wilmott (2003) Educational management in managerialist times: beyond the textual apologists (Buckingham, Open University). Toynbee, Polly (2007) ‘Re-thinking Humanity in Care Work’, in S. Bolton and M. Houlihan, eds, Searching for the Human in Human Resource Management (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan), 219-243. i Similar challenges are faced by men who do not conform to the hegemonic masculine norm. As Mills (2002) observes, while organisational culture is never gender neutral, it is dynamic, fluid and changing and men and women are both positioned and position themselves differently, depending on the traditions and context of the organisation itself. 21