Science and Religion: Conflict and Triumph (Wk8)

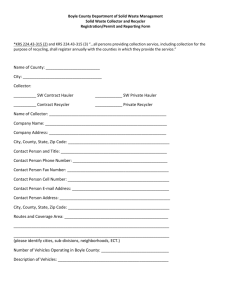

advertisement

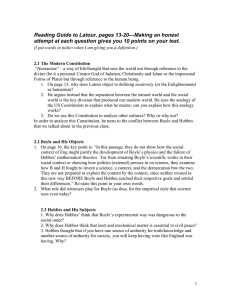

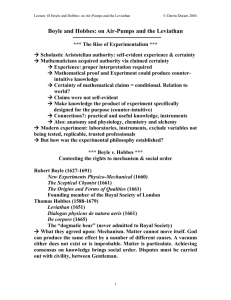

Science and Religion: Conflict and Triumph (Wk8) The idea of a conflict between the two begins in the C19 with the works of Draper and White. Draper emphasised the incompatibility of Catholicism and science while White was interested in the warfare between science and theology, which he saw as the fault of dogmatic religion. He collected evidence of the interference of religion in science and saw direct evidence of this in both science and religion. White was president of Cornell University and saw the university as an “asylum for science” with no religious element to selection or to the general culture. The introduction of Darwin’s Origin of Species led to greater divisions between science and religion. But the idea of an absolute split between the two is exaggerated. Many books maintained the idea of a harmony between the two, supporting a C17 rationale of the relationship between science and religion. Many authors however had vested interests in wanting to prove the compatibility between science and religion, consequently care was, and is, needed in choosing between the two arguments in order to avoid polarisation. C17 scientists were deeply religious. Robert Boyle was a born again Christian who saw science as integral to religion. He compared scientists to priests, seeing both as searching for evidence of God and science as linked to, if not inspired by, religion. The vast majority of people maintained a conviction in the absolute power of God. Mechanical philosophy was based on the need for an intelligent power and the limits to human knowledge were linked to a distinctly theological outlook. The presumption was that humans strive to know everything. This profound religious commitment was bounded by the distinction between natural philosophy and religion, Boyle going so far as to separate his books into two separate groups, writing as a philosopher, and not a Christian, in his philosophy books in an attempt to demarcate separate spheres. Bacon was concerned over the possible corruption of the study of nature by confusion with the study of theology and the dangers within this to both fields. Galileo saw the Bible as an unreliable source for many physical matters. He regarded physics as an appropriate means of interpreting the Bible, in effect subordinating the Bible to science, while hoping to maintain the two as separate. Thomas Spratt (historian of the Royal Society regarded experiments as purely empirical and so having no need for a religious element. His latitudinarian attitude was in line with much of the thinking of the time as to nature and the range and wonder of Gods works. The segregation of religion and science was necessary for the harmony of the two. This was not an antireligious attitude but the increasing segregation led to an increased opportunity for science to develop along a separate route. This idea of harmony was mainly in evidence in the late C17, but there was an increasing sense that some incompatibility remained. It was this that influenced scientific attitudes, in that it tempered ideas through fear that they might be considered as irreligious and led to concern with respect to the comments of others. Boyle considered himself a “naturalist without being an atheist” and saw no conflict between science and religion. These ideas had their foundation in the works of Epicurus and Lucretius who had a mechanical view of the World in which gods played no part. The failure of Gassendi to successfully rehabilitate the atomism of Epicurus was also a failure to separate the moral elements of religion. Similarly Pomponazzi failed to remove the religious element with regard to how Aristotelianism was perceived. Was nature self-sustaining as he and Aristotle had suggested or was there a need to invoke the hand of God. The question was whether nature was a system that ran itself? This idea was attacked by Boyle who saw a need to argue for a role for God. Hobbes Leviathan (1651) was seen as a cynical view of society and associated with the mechanical view of nature. This led to an inevitable conflict between Hobbes and Boyle who wanted to represent the idea of both the church and science and who’s subsequent attacks on Hobbes were on purely religious grounds in the hope of containing Hobbes influence on others. Hobbes cynical view followed in the tradition of Machiavelli. The origins of modern atheism have more to do with politics than science in that the challenge to religion is from a social rather than a scientific perspective. The growth of educated scepticism, with science playing a positive role in religion, was a true belief rather than a ploy to gain acceptance. It saw the movement of science from defensive to offensive with regard to the attitudes between science and religion, with science able to contribute to the theistic consensus with the idea that the evidence of nature was irresistible with respect to the idea of an intelligent creator. Bentley made use of science to show the influence of God in Newton’s Principia and the use of the concept of force – as both quantifiable, non-mechanical and above the mechanical ideas of the universe – as divine. Similar arguments were proposed by William Derham with regard to the physiology of plants and animals. John Ray wrote one of the most popular science books of the period in which he argued that the deity was obvious in the function of all thins and in their inter-relationship in the universe. These ideas have considerable staying power and are prevalent today. C18 scientific studies related to religion made people more religious by showing them the wonder of nature and therefore the wonder of God. Science was religions best support by promoting the idea of harmony. Both Boyle and Ray saw complete compatibility between science and religion. Where then did the growth of atheism come from and what was the relationship between science and religion in places other than England?