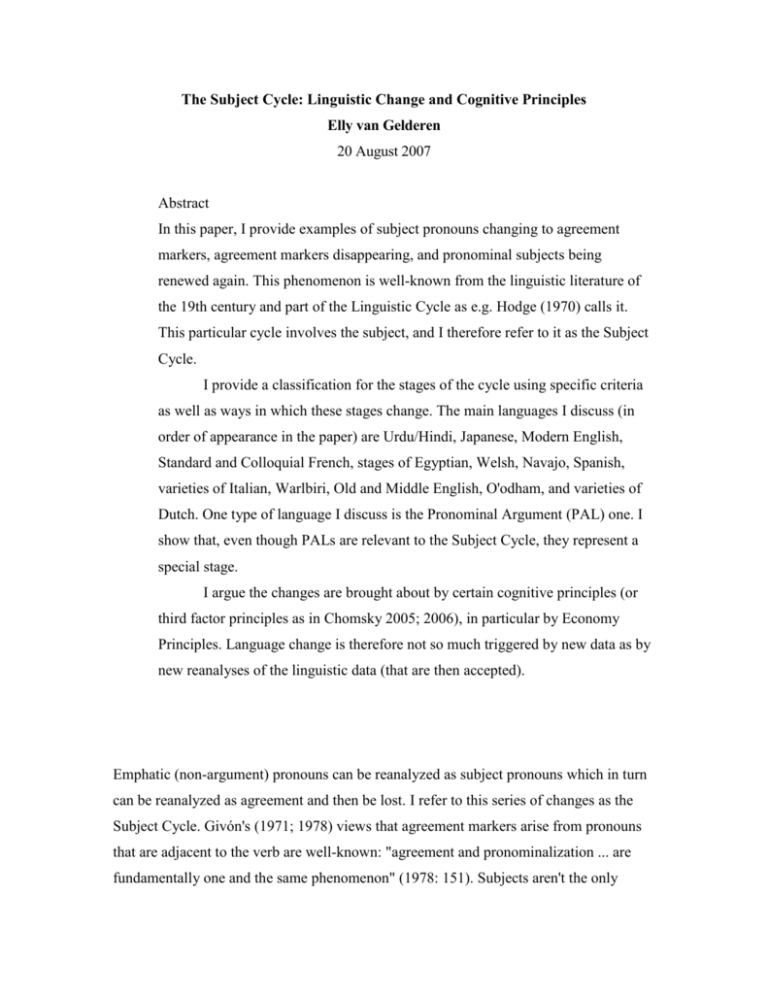

Givon 1971 `today`s morphology is yesterday`s syntax` (quoted in

advertisement