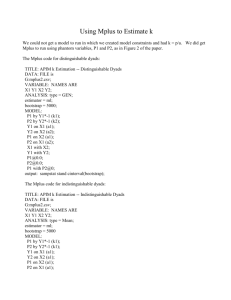

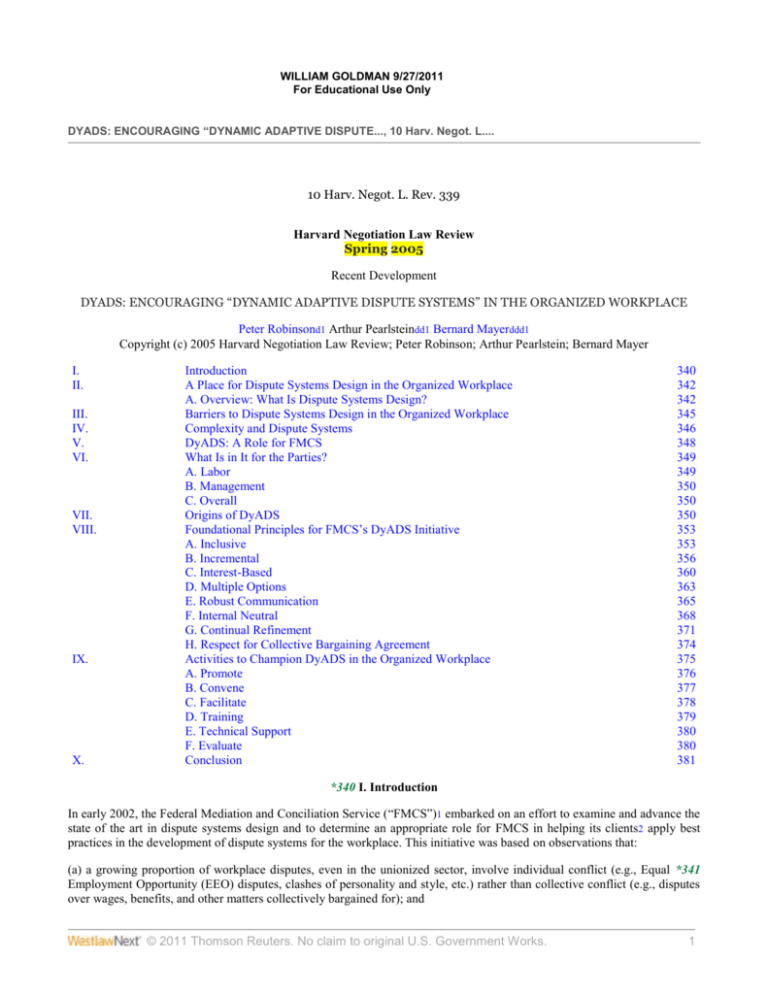

Dynamic Adaptive Dispute Systems

advertisement