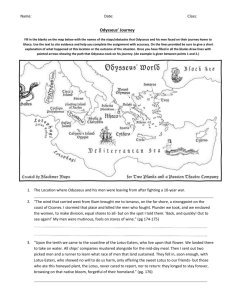

Reading Summaries

advertisement