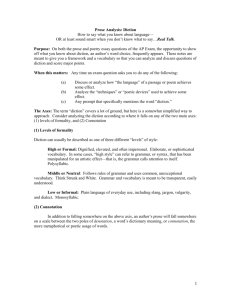

1 Diction Levels of Formality – the higher ratio of polysyllabic words

advertisement

Diction “The difference between the right word and almost the right word is like the difference between lightening and the lightening bug.” 1 --Mark Twain Levels of Formality – the higher ratio of polysyllabic words, the more difficult the content 1. High or Formal: Dignified, elevated, and often impersonal. Elaborate, or sophisticated vocabulary. In some cases, “high style” can refer to grammar, or syntax, that has been manipulated for an artistic effect—that is, the grammar calls attention to itself. Polysyllabic. Words Characterizing Formal Diction: cultured, learned, pretentious, archaic, scholarly, pedantic, ornate, elegant, flowery EXAMPLE: The respite from study was devoted to a sojourn at the ancestral mansion. 2. Middle or Neutral: Follows rules of grammar and uses common, unexceptional vocabulary. Think Strunk and White. Grammar and vocabulary is meant to be transparent, easily understood. Words Characterizing Neutral Diction: unadorned, plain, detached, simple EXAMPLE: I spent my vacation at the house of my grandparents. 3. Low or Informal: Plain language of everyday use, including slang, jargon, vulgarity, and dialect. Monosyllabic. Words Characterizing Informal Diction: abrupt, terse, laconic, slang, homespun, jargon, colloquial, vulgar EXAMPLE: I crashed at Grannie’s. Connotation – the more metaphorical or poetic usage of words (as opposed to denotation – dictionary meaning). Learn to use the following words to address this aspect of diction: Denotative descriptors are: literal, exact, journalistic, straightforward Connotative descriptors are: poetic, metaphoric, picturesque, lyrical, obscure, figurative, sensuous, symbolic, grotesque Denotative public servant law officer investigator Connotative bureaucrat cop spy Abstraction – does the author write about something you can hold in your hands or only hold in your head? Specificity – how clear is the image? General look cry throw Specific gaze, stare, peer, squint, ogle weep, sob, sigh, bawl, blubber hurl, pitch, toss, dump, flip The “Music” – do the words sound nice? If so, you can talk about the euphony of the passage. If it sounds harsh, talk about that and the relationship to meaning. Euphonious Through the drizzling rain, on the bald street, breaks the blank day. Cacophonous Their lean and flashy songs grate on their scrannel pipes of wretched straw. Figures of Speech – personification, metaphor, paradox, alliteration, etc. NOTE: Sample Analysis Questions 1. 2. Why is the diction formal or informal? Colloquial? Slang? Jargon? Archaic? Do the words have interesting connotations? Is the passage especially denotative? What effect does this have? 3. Is the language concrete or abstract? General or specific? What effect does this have? 4. Do any words seem especially cacophonous (harsh sounding) or euphonious (pleasant sounding)? 5. Are there any figures of speech? 6. What is the subject of the piece? Do the words fit the subject well? Explain. 7. Who is the audience for the piece? Are the words appropriate for the audience? Explain. 8. What is the author’s purpose in writing the piece? Do the words reinforce the purpose? Explain. 9. Does the author use archaic words, colloquialism, jargon, profanity, slang, trite expressions, or vulgarity? If so, what effect do these have in the piece? 10. Is there any change in the level of diction in the passage? 11. What can the reader infer about the speaker or speaker’s attitude from the word choice? (See tone) Never substitute terminology for analysis. Always connect the literary term (and example) directly to the effect it creates in the passage or the effect it has on the reader. No element should be considered in isolation: The importance of any element is how it works with others to convey the writer’s purpose. Diction 2 A Five-Step Process for Using Your Great New Terminology to Devise Intelligent and Specific Topic Sentences First: DON’T say that the author “uses diction.” You are saying nothing if you say that. Everyone uses “word choice”—your job is to characterize that word choice AND determine why it was used. Step One: Levels of Formality 1. “Do” a close reading on the passage, first identifying any unusual or characteristic words. If there are none, you are probably reading something with a “middle style.” 2. If words stand out, you should be able to decide whether the passage leans to the high or low styles. If so, pick a snazzy vocab word to describe what kind of high or low diction it is. Step Two: Connotation 1. Examine how the words appear to be used—do they seem to be used like poetry, with lots of external, thematic meanings attached, or are they more literal, like a straightforward action story? 2. Once you decide which way it leans, connotative or denotative, pick some vocab words that characterize the diction more specifically. Step Three: Miscellaneous 1. Ask yourself about abstraction and specificity, what figures of speech you see, and the sounds of the language. Step Four: Purpose 1. Sit back for a moment and ask yourself what purpose of the word choice appears to be fulfilling. 2. For example, you can always say that it sets a tone—just make sure you have some words ready to describe that tone. 3. Also consider whether the word choice is having an effect on character, symbol/theme, setting, etc. Step Five: The topic sentence. “In [name of work], [Author] writes in a [connotation] [level of formality] style. Her use of [connotation vocab] and [level of formality vocab] language [achieves this purpose].” For example: “In Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad writes in a highly connotative formal style. His use of abstract, poetic, and ornate language establishes existential themes of fate and meaninglessness.” DICTION STUDY: THE RATTLER WRITING ASSIGMENT: Read the following passage carefully. In a well-developed essay, discuss the effect the passage has on the reader by analyzing the techniques used by the writer to achieve that effect. You should consider such elements as diction, syntax, point of view, and organization. After sunset…I walked out into the desert…Light was thinning; the scrub’s day savory odors were sweet on the cooler air. In this, the first pleasant moment for a walk after long blazing hours, I thought I was the only thing abroad. Abruptly, I stopped short. The other lay rigid, as suddenly arrested, his body undulant; the head was not drawn back to strike, but was merely turned a little to watch what I would do. It was a rattlesnake—and I knew it. I mean that where a six-foot blacksnake thick as my wrist, capable of long-range attack and armed with powerful fangs, will flee at sight of man, the rattler felt no necessity of getting out of anybody’s path. He held his ground in calm watchfulness; he was not even rattling yet, much less was he coiled; he was waiting for me to show my intentions. My first instinct was to let him go his way and I would go mine, and with this he would have been well content. I have never killed an animal I was not obliged to kill; the sport in taking life is a satisfaction I can’t feel. But I reflected that there were children, dogs, horses at the ranch, as well as men and women lightly shod; my duty, plainly, was to kill the snake. I went back to ranch house, got a hoe, and returned. The rattler has not moved; he lay there like a live wire. But he saw the how. Now indeed his tail twitched, the tocsin sounded; he drew back his head and I raised my weapon. Quicker than I could strike, he shot into a dense bush and set up his rattling. He shook and shook his fair but furious signal, quite sportingly warning me that I had made an unprovoked attack, attempted to take his life, and that if I persisted he would have no choice but to take mine if he could. I listened for a minute to this little song of death. It was not ugly, though it was ominous. It said that life was dear, and would be dearly sold. And I reached into the paper-bag bush with my hoe and, hacking about, soon dragged him out of it with his back broken. He struck passionately once more at the hoe; but a moment later his neck was broken, and he was soon dead. Technically, that is; he was still twitching, and when I picked him up by the tail, some consequent jar, and some mechanical reflex made his jaws gape and snap once more — proving that a dead snake may still bite. There was blood in his mouth and poison dripping from his fangs; it was all a nasty sight, pitiful now that it was done. I did not cut off the rattles for a trophy; I let him drop into the close green guardianship of the paper-bag bush. Then for a moment I could see him as I might have let him go, sinuous and selfrespecting in departure over the twilit sands. A sample response on diction might be set up this way: The author’s techniques used in “The Rattler” convey not only a feeling of sadness and remorse but also a sense of the man’s acceptance of the snake’s impending death. A human being has confronted nature, and in order for him to survive, the snake must be killed. The diction and figures of speech, especially the images, similes, and metaphors, create sympathy in the reader for the man’s plight and a reluctant, sad agreement with him for his decision. The author’s diction, largely concrete and informal in order to convey the confrontation, heightens the power and force behind the snake as it responds to the man. “Arrested” at first, the snake becomes a “live wire” as he shakes his “little tocsin” at the man. Unmoving at first, the snake plays a waiting fame as adversary meets adversary across an imaginary line drawn in the desert sand. Then a feeling of electricity jolts the reader, heart beating faster from the noise of the warning that, like battle stations abroad a ship, calls all to readiness. Yet it must lose; despite its attempts to hide in the “paper-bag bush,” the snake knows its life has been “dearly sold,” but it remains a “sinuous and self-respecting” in the man’s mind. The hiding place is an illusion, and a costly one. The reader admires the valiant behavior of the snake’s last moments and the dignity which the man offers. All involved recognize the strength of both the man and the almosthuman snake, but know that responsibility and duty to others make the killing necessary. The figures of speech…