John Echeverri-Gent - University of Wisconsin Law School

advertisement

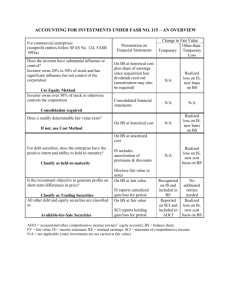

Why Do Some Financial Markets Develop and Others Do Not? Politics of India’s Capital Market Reform Paper presented to the Workshop on States, Development, and Global Governance March 12-13, 2010 Lubar Commons, University of Wisconsin Law School John Echeverri-Gent Department of Politics University of Virginia Email: johneg@virginia.edu 1 Why Do Some Financial Markets Develop and Others Do Not? Politics of India’s Capital Market Reform “A casual observer might infer from India’s flourishing stock markets, fast-growing mutual funds, and capable private banks that the financial system is one of the country’s strengths. But closer inspection reveals that while policy makers deserve credit for liberating these high-performing parts of the [financial] system, tight government control over almost every other part is undermining India’s overall economic performance.”1 Economic historian Douglass North has observed, “it is a peculiar fact that the literature on economics … contains so little discussion of the central institution that underlies neoclassical economics – the market.”2 Until recently, this neglect was particularly true for analysis of how markets change. Though more recently, economic historians like Douglass North, John McMillan, and Avner Grief have documented the changes in markets over time, the analysis of how markets change is still in early phases of development.3 My paper takes advantage of the uneven nature of capital market reform in India to offer some modest steps towards advancing our thinking. It poses the question: “Why have India’s equity markets experienced such dramatic reform while its market for government securities have lagged behind, and the limited reforms in the market for corporate debt have failed miserably?” Implicit in this question is a distinctive and somewhat fine-grained definition of “market.” While economists have delivered great insights on the functioning of markets, comparative economics has not always carefully defined the concept of markets. Many analysts talk about market economies as a national unit of analysis. They compare market vs. non-market economies or different varieties of capitalist markets. Other analysts conceptualize markets in sectoral terms, at either the international or national level. They examine energy markets, agricultural markets, financial markets, etc. Still others discuss regional markets. For the purposes of this papers analysis, I define markets in terms of the technologies and rules that regulate the transactions of market participants. I distinguish market along three dimensions: 1) the technologies and rules that structure the transactions of market participants, or what I call market design; 2) the nature of the goods that are exchanged; and 3) the identity of the participants. A single market is the intersection of these three dimensions. If the same market design is used for transactions of two different commodities and for two different sets of participants, there will be at least two markets distinguished by sectoral or spatial dimensions. If the same commodity is traded according to different market designs and/or among different 2 positions, there will be distinctive markets. Similarly, if the same participants engage in transactions of according to different market designs and/or they trade different commodities there will be distinctive markets. Following from this definition is a conceptualization of how to measure market development. I measure market development along three dimensions. Markets develop as they adopt more efficient market designs. The efficiency of market design has two indicators. A more efficient market will have lower transaction costs. It will also have more efficient price discovery. Secondly, more advanced markets will have more efficient competition. My idea of more efficient competition differs from notions of “perfect competition” in that the number of participants that achieve efficient competition will vary with the nature of the good being traded. Finally, I measure market development in terms of the sophistication of its regulation. The sophistication of regulation is measured in terms of the extent to which the regulation facilitates efficient competition and innovation in terms of market design and goods traded. My analysis leads me to adopt somewhat distinctive units of analysis. Some scholars speak of India’s financial sector, a concept that includes the money market, credit market, and capital market. Other scholars analyze India’s capital markets conceptualizing them as including the equity market and the debt market which encompasses the market for government securities and corporate debt. There are good reasons for grouping government securities and corporate debt into a single market since they are interdependent. In particular, the yield curves established for government securities are an important benchmark for corporate debt issues. Also, it is important to keep in mind that India’s financial markets, like financial markets around the world, are becoming increasingly interdependent. Nonetheless, I examine the equity, government securities, and corporate debt markets as being distinct in the Indian case because they are characterized by different market designs, traded goods, market participants, and regulatory regimes. There are three analytical perspectives explaining financial market development. First, is the Legal Origins Perspective.4 The premise of the legal origins perspective is that founding legal systems on different principles creates systematic variation in legal systems across countries with the basic variation being between Anglo-Saxon common law traditions and continental European civil law traditions. Variation between these legal traditions can be quantified and has a significant impact of economic outcomes. Common law traditions because of its greater judicial independence and pragmatic approach to resolving legal problems provides greater legal protection for minority shareholders, better contract enforcement, and thus support more rapid financial development in times of stability. Civil law is associated with less flexible dispute resolution, greater government intervention and associated corruption and therefore leads to less respect for private property and the development of less efficient financial markets. Second is the “Constructivist Crisis” perspective.5 This perspective views crises as critical junctures that provide opportunities for dramatic change. Rather than 3 characterizing crises as exogenous shocks to equilibrated systems or events that dramatically alter balances of power, recent proponents have highlighted how crises disrupt and delegitimize norms and cognitive understandings of circumstances. Consequently, crises provide opportunities for agents construct meanings which in turn structure understandings of interests and the evaluation of policy alternatives. The approach highlights the role of ideas in shaping actors’ perceptions of their interests, and ultimately, the responses to economic crises. The third perspective is the political power approach. It began with a focus on the role of political institutions in restraining the arbitrary abuse of government authority and bolstering its credible commitment to property rights.6 More recently advocates have added a focus on institutions that promote political competition such as separation of powers, federalism, and electoral suffrage.7 Advocates working in the tradition of this perspective have recently endeavored to extend their analysis “beyond formal institutions of competitive elections and political checks and balances.”8 Keefer, for instance, observes that there is considerable variability in the accountability of political authorities among competitive political systems. Pointing out that secure property rights and efficient markets are public goods, he finds that variables that align politicians incentives to provide public goods – i.e. variables that affect the credibility of their promises to deliver public goods such as the years of continuous competitive elections and voter information about public policies – are in some ways stronger determinants of financial market development than institutional checks and balances.9 Rajan and Zingales point out that governments can – and historically have – reversed their support for political institutions.10 The institutional argument is incomplete. Enduring institutional commitments are the culmination, rather than the source, of changes in a balance of power. In their view, “It is more fruitful to think if the devolution of political power and the security of property as intertwined processes in which secure property eventually became the fount of political power.” 11 Drawing on these positions, the political power perspective will investigate how institutional change is shaped by the exercise power. This paper argues that though law plays a crucial role in the development of financial markets, the legal origins perspective is not well suited to explain the variation of market reform and development in India’s equity, government securities, and debt market. It contends that while interpretation of economic crises played an important role in shaping the development of India’s capital markets, their impact was structured by the configuration of political power – in particular the power and authority of state agencies like the Reserve Bank of India and the Ministry of Finance – and the structure of institutional capabilities that comprised the context of the reforms. India’s Capital Markets Before the Reforms Though India had one of the most regulated non-communist economies of the world until the 1990s, few sectors were as dominated by the state as finance.12 Two objectives motivated the Indian state’s control over its capital markets: funding the government’s fiscal deficits in a non-inflationary manner and directing capital to sectors and firms that state planners designated as priorities. Though India had long-standing 4 financial institutions, it suffered from severe financial repression and underdeveloped markets at the onset of the reform era in the early 1990s. Equity Markets Indian equity markets were stunted by heavy handed state regulation and a monopoly of stock brokers. All companies wishing to raise capital from the primary market needed to get the approval of the Controller of Capital Issues (CCI). The CCI was created under the Capital Issues Controller Act (1947) which itself was influenced by the controls over the issues of capital instituted by the British during World War II. The CCI was not only the gatekeeper to the primary market, but it determined the number and price of shares or debentures that could be issued. The formula that it used to determine the prices of new issues consistently assigned sub-market prices and led to oversubscription to new issues by investors strategies by promoters and brokers to take advantage of the investor’s frenzy. Though the Ministry of Finance exercised legal authority over India’s secondary equity markets under the Securities Contracts (Regulation) Act 1956, it delegated most of the regulation of the secondary market to the stock exchanges as self-regulatory organizations. Due to poor communications infrastructure and a legal provision that companies must list on at least two exchanges, India had twenty regional stock exchanges at the end of the 1980’s. However, the largest and most prestigious, the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) dominated the system. Virtually all of India’s large corporations listed on it, and it had by far the largest capitalization and trading volume. Access to trading on the BSE was controlled by the 554 broker-members of the BSE. 13 The broker-members controlled the exchange management through annual elections to the governing board of the exchange. The governing board’s regulation of the exchange was broker-friendly to an extreme degree, often at the expense of investors. The exchange management often delayed settlements when brokers were having difficulty meeting their financial obligations, and it allowed brokers to mix their trade accounts with the accounts of their clients. With the advent of computerized trading the exchanges’ market design – based on an open-outcry system with jobbers – market makers to infuse liquidity – grew increasingly outdated. It also suffered a fundamental design flaw in the form of badla, a carry forward system of finance that served as a means of hedging by enabling traders to manage their risk by postponing payment from one settlement to the next. However, unlike derivatives, which are traded on a separate exchange, badla trading is mixed with the cash market and therefore distorts price discovery. The capacity to distort prices on the cash market made badla attractive to speculators wishing to profit by creating false market signals. The public sector Unit Trust of India (UTI) had a monopoly over the mutual fund sector until 1986. It was widely believed that the state issued instructions to the UTI – arguably largest and most influential trader on the secondary market– to influence prices.14 The Market for Government Securities “The genius of the Indian economy,” remarked Larry Summers, “is its ability to run high fiscal deficits as much as 10 % of GDP while keeping the rate of inflation low.”15 The Indian state – through the Finance Ministry – was able to accomplish this 5 feat through forceful repression of the market for government securities. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the country’s central bank, lacked autonomy from the government in exercising its role as banker to the state and monetary policy authority.16 Through the 1990’s the RBI automatically monetized the fiscal deficit at the government’s behest. After the government nationalized 14 of the largest commercial banks in July 1969 -which together with the already publicly owned State Bank of India accounted for 86 percent of deposits, it forced the banks to serve as a “captive market” for low cost finance for the fiscal deficit.17 There was no real market – primary or secondary – for government securities. When the government issued treasury bills at administratively determined interest rates to pay for its fiscal deficit, the RBI either absorbed them itself, or it telephoned a bank and requested that they purchase them. The government ensured that the banks would purchase its securities by raising their Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) – the share of net demand and time deposits that banks have to maintain in cash, gold and approved securities – from 25 percent in 1964 to as high as 38.5 percent in 1990. It also increased the Cash Reserve Ratio – for which banks were required to hold cash, gold and securities – from 3 percent to 15 percent of their net demand and time deposits.18 The secondary market for the low interest government securities was limited. There was no exchange, rather trading took place through bilateral negotiations over the telephone between banks and other financial institutions often-times facilitated by brokers. The public was excluded, and given the poor condition of India’s telephone infrastructure up to the 1990s, virtually all trading took place within the South Mumbai financial center.19 The RBI’s Public Debt Office served as a depository for government securities. It recorded transactions by physically entering them a subsidiary general ledger (SGL) on the request from the sellers. Record keeping was notoriously inefficient, often falling weeks behind, and it was not uncommon for a financial institution’s payments to bounce because the record-keeping was behind.20 These inefficiencies prompted traders to begin trading IOU’s called “bankers receipts” that played a role in the 1992 scandal. The Market for Corporate Debt The market for corporate debt was extremely limited through the 1980s. The CCI allowed the sale of a limited number of corporate debentures, but most investment was secured through loans by banks and financial institutions. The Indian state was concerned to ration scarce capital to priority sectors. Before initiating a new project or expanding an existing one, promoters needed to secure an investment license from the government. With a license in hand, industrial projects were eminently profitably because the licensing system created strong barriers to entry that limited competition. Commercial bank loans were limited nonetheless, because they presented the banks with an asset liability mismatch and the banks lacked project appraisal skills necessary for technologically complex ventures. The state established development financial institutions (DFI’s) including the Industrial Development Bank of India, the Industrial Credit and Investment Corporation of India, the Shipping Credit and Investment Company of India, the Industrial Finance Corporation of India, and the Small Industries Development Bank to finance industrial projects. It provided the DFI’s with subsidized 6 funding to provide term loans or subscribe to debentures. The DFI’s played an increasingly important role in financing industrial development through the 1980s. According to one study, they contributed more than 60 percent of all financial assistance to the industrial sector in this decade.21 However, by the end of the 1980s, there was mounting evidence of political intervention into the DFI’s credit allocation decisions.22 In 1986, public sector enterprises were permitted to enter the market for corporate debt to reduce the fiscally strapped government’s need to provide them with finance. There was no market infrastructure for trading corporate debt. There was no mechanism in place for settlement. Most of the debt instruments remained with financial institutions that preferred to hold rather than trade. Reforming India’s Capital Markets During the last decade significant quantum changes have taken place in the quality of the equity market. In terms of efficiency and transparency it is now ranked among one of the best markets globally. In contrast, the corporate debt market continues to remain in a highly underdeveloped state.23 India’s capital market reforms have been skewed. Equity market reforms have led the way. Reforms in the market for government securities have followed with some delay. There has been very little reform of the market for corporate debt. In this section, I describe the reforms in each market. I begin my examining the impact of reforms on the number and nature of market participants. Then I investigate changes in market design. Finally, I explore reforms in market regulation. India’s equity market reforms The markets for India’s equities have traveled farthest and fastest. Reforms removed important barriers to entry for market participants shortly beginning in 1992. Foreign Institutional Investors (FII’s) were given access to Indian equity markets in September 1992, and they have become dynamic actors providing greater liquidity as well as volatility. Some have argued that the FII’s themselves have become forces for change bringing pressure for changing the clearing and settlement systems. In 1993, private sector mutual funds were permitted to enter the market. Their entrance ended has ended the domination of the UTI. As the years progressed and the private sector mutual funds began to dwarf the UTI, it has become increasingly impossible for the government to use UTI to affect market prices. Finally, the establishment of the National Stock Exchange (NSE) – in conjunction with the presence of FII’s – has contributed to a great transformation of Indian brokerages. The supplanting of undercapitalized proprietors and partnerships by better endowed corporate brokerages has led to less focus on earning profits by finding ways to manipulate the market and more attention to investing in human capital to master new trading technologies, more sophisticated risk management, and the use and innovation of new financial products. The advent of the NSE with its 7 nation-wide satellite network has made India’s equity markets more accessible to investors outside of Mumbai and therefore dramatically expanded market turnover. Table 1: Reform of India’s Capital Markets Equity Market 1992 FII’s given Market market access Participants 1993 Private Sector Mutual Funds 1994 NSE increases corporate brokers 1996 SEBI tightens disclosure rules for primary issues 1994 Electronic Market order-book Design trading system 1996 NSDL 1996 NSCCL 2000 Derivatives trading 2001 Rolling Settlement Regulation 1992 CCI abolished SEBI given statory authority 1994 Exchange demutualization begins w/ NSE 1996 Sebi tightens disclosure rules for primary issues Govt. Securities Market 1995 Primary Dealers 2001 FII’s with 100% debt funds given limited investment 2006 RBI withdraws from primary market Corporate Bond Market 2001 FIIs investment allowed 2008 FII investment ceiling raised from $1.5 bn. to $8 bn. 1992 RBI introduces Repos 1993 SGL computerized Delivery vs. Payment introduced 1997 W&M ends automatic monetarization 2002 CCIL & NDS 2005 NDS-OM 1992- SLR reduced 97 from 38.5% to 25% 1992- CRR reduced from 15% to 5% 1994 NSE WDM enables electronic reporting 2004 SEBI orders mandatory reporting 1992 CCI abolished SEBI given statutory authority 1996 Sebi tightens disclosure rules for primary issues India’s equity market design was also rapidly transformed. The NSE introduced an electronic order-book trading system that transported trading from the chaotic openoutcry floor of the BSE building in South Mumbai to the air conditioned offices of brokers across the country. Later, the development of web-based trading shifted trading into the homes of millions of investors. The new trading system enabled anonymous trading and minimized the personal favoritism that had previously characterized market trading. It eliminated the need for “jobbers” (market makers) as intermediaries injecting liquidity into the market by offering buy and sell quotes. The reform of the clearing 8 system through the establishment of the National Securities Clearing Corporation Ltd. (NCSSL) eliminates counter-party risk by inserting the NCSSL counter-party to all buyers and sellers In so doing, it greatly diminishes the risk that default by buyers or sellers will create a risk to the broader system. It also introduces a specialized division of labor enabling the NSE to concentrate on managing the trading system while the NCSSL focuses on evaluating counter-party risk. The creation of an electronic depository, the National Securities Depository Ltd. (NSDL) in 1996, and the proliferation of dematerialized shares greatly diminished the transaction costs of storing and trading physical certificates in the context of the limitations of India’s transport and communications systems. It also put an end to counterfeit certificate scams. In June 2000, the government authorized derivatives trading. This, along with the changes brought about by the NCSSL and the NSDL, made it possible to replace the weekly settlement system with a T+3 rolling settlement in 2001. In 2003, settlement efficiency had increased so to the extent that the government introduced a T+2 system, one of the quickest in the world The abolition of the CCI and the authorization of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) in 1992 brought about an important shift in regulation. No longer did the state intervene to dictate market outcomes as it did with the CCI. With the empowerment of the SEBI, regulation now enforced trading rules to enhance efficiency, transparency, and equity. SEBI took measures to enhance the transparency of the primary market by issuing new rules to improve the disclosure initial public offerings. It also issued new rules to regulate insider trading. The regulator played a cautious role in development the market by issuing rules to that replaced badla with trading in derivatives and rolling settlement. SEBI was a specialized agency that was able to focus on its mission to provide effective regulation since it does not trade in the market and does not own market infrastructure. As a new agency, SEBI was less constrained by the institutional legacies of India’s pre-reform dirigiste financial system, and it succeeded in focusing its mission on promoting effective speculative price discovery in the markets that it regulated.24 The establishment of the NSE in 1994 involved another key change in equity market regulation, the demutualization of stock exchanges – a process that has radically transformed stock exchange management and self-regulation. By publicly selling equity in the exchanges, demutualization separates ownership from management and places the exchanges under professional management that does not suffer the conflict of interest that plagued India’s broker managed exchanges. In 2005, SEBI ordered the demutualization of all exchanges, and by the spring of 2007, all major exchanges have been demutualized. India’s government securities market reform Reform of the government securities market has been slower and somewhat less substantial. A key change has been gradual transformation of the role of the RBI. Through the early 1990s, the RBI basically used the primary market for government securities as a means to manage the government’s growing debt by selling its securities to captive purchasers at interest rates that it set at below market levels. The secondary market for government securities consisted primarily of financial institutions that bought 9 and sold government securities to meet statutory liquidity ratio requirement which reached as high as 38.5% of deposits and Cash Reserve Ratios as high as 15%. In 1995, the government introduced measures to create a system of primary dealers who are authorized to participate to purchase securities through auctions on the primary market and resell them on the secondary market by offering quotes for sales and purchases, in a manner similar to that of the market makers in the equity market. In fall 2008, there were 19 primary market dealers. From 1995 to 2006 the RBI intervened in the primary market to smooth undesirable market fluctuations. As stipulated by the 2003 Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act, RBI intervention in the primary market was terminated in April 2006. Foreign Institutional Investors were permitted to participate in the government securities market only in 2001, but the government cautiously restricted their participation by limiting their purchases to a maximum of $500 million. In 2007, the limit was raised to $1.5 billion. There was a retail market for government securities traded on the Retail Debt Market segments of the NSE, BSE and Over the Counter Exchange of India (OTCEI), but trading volumes remained very low. The RBI has implemented significant changes in the market design for trading government securities. In 1993, the computerization of the archaic and inefficient SGL eliminated the opportunities for the fraud that had occurred, but the restrictions on information access and user services provided by the SGL as compared to the NSDL means the former has less impact in facilitating trade.25 Clearing in the government securities market (as well foreign exchange and money market transactions) has been reformed with the operation of the Clearing Corporation of India Ltd. (CCIL) established at the initiative of the RBI in on April 30, 2001. R. H. Patil, a important force behind the establishment of the NCCSL as the first managing director of the NSE, also played a key role in setting up the CCIL.26 The CCIL uses the same techniques as the NCCSL to minimize counterparty and systemic risk in the clearing process. The CCIL initiated operations on November 15, 2002 with an electronic platform called the Negotiated Dealing System (NDS) which was created to enable traders to negotiate deals more efficiently. Initially the NDS was used primarily as part of the system for clearing and settlement while trading continued to take place through bilateral negotiations over the telephone. In 2005, the RBI sponsored the creation of the NDS-OM as an electronic, screen-based, order driven trading system to improve price discovery, liquidity, and operational efficiency. On January 3, 2007, the CCIL launched NDS-Auction an electronic auction module for bidding in primary treasury bill auctions. During the reform period, the RBI has launched a number of new trading instruments including repurchase agreements (repos), reverse repos, securities with fixed coupon rates, floating rate bonds, zero coupon bonds, and capital indexed bonds. Though a lot of new software has been incorporated into the trading systems for government securities, liquidity in the secondary market remains low, and more than 73 percent ownership of all central and state government securities remains in the hands of captive buyers such as commercial banks and the Life Insurance Corporation of India or the RBI itself.27 The reduction in Statutory Liquidity Ratios from 38.5% to 25% and Cash Reserve Ratios from 15% to 5% has been important changes in the regulation of the market because they have reduced the obligations of financial institutions to purchase 10 government securities. Otherwise, the market remains regulated by the RBI. Unlike India’s equity markets that are regulated by an independent regulatory agency whose responsibilities are exclusively to regulate trading on exchanges, India’s market for government securities are regulated by the RBI which suffers from potential conflicts of interest due to its multiple roles as banker to the government, monetary policy authority, and financial participant – through capital ownership and subsidies – in primary dealers, banks, and financial institutions who trade in the market. Corporate Bond Market The stunted development India’s the corporate bond market presents a puzzle in light of the apparent opportunity costs of inaction and the possibilities for change. Development of the corporate bond market should have been spurred by the abolition of the CCI and the end of government control over interest rates for corporate bonds. The gradual lowering of barriers to trade that began during the 1990s and the consequent increase in foreign competition also should have spurred demand for corporate debt, especially with the simultaneous slashing of DFI finance that has occurred with the end of financial system based on industrial licensing and subsidized government funding of the DFIs. Demand for bond market development should also be spurred by India’s need for immense investments in its infrastructure estimated at $475 billion from 2007-2012.28 The allocative inefficiencies that result from the underdevelopment of the corporate bond sector and the consequent under-provision of capital to the private sector corporations – India’s most efficient sector – also creates incentives to reform.29 The lack of reform is made more puzzling by the ready availability of more efficient market institutions already adopted by India’s equity market and diffused into the market for government securities. In order to understand the limits of reforms in the corporate bond market it is helpful to consider three factors: limits on the supply of corporate bonds; limits on demand, and measures to improve the market design. Regulations that create disincentives for participation in the corporate bond market are an important reason for its limited development. While the abolition of the CCI eliminated the government’s gatekeeper to the market, the requirements for disclosure and listing debt issues imposed by SEBI in 1996 are widely viewed as unduly burdensome. In addition issues on the primary market are also discouraged by a stamp duty which is high by international standards and which adds the inconvenience of varying across individual states. Demand for private corporate bonds is also limited. Though they have begun a period of rapid growth, India’s pension and insurance sectors are underdeveloped by international standards. Private bond holding in these sectors is preempted by laws requiring that public sector securities account for at least 25% of banks’ total deposits, 50% of life insurers assets 30% of other insurer’s assets; and 40% of the assets owned by India’s largest provident fund. Pension fund investments in private corporate bonds are restricted to 10 percent of yearly accruals. In many developing countries, foreign institutional investors have contributed to the development of corporate bond markets. In India, there role has been limited by low, but recently increasing, limits on their investments. Banks prefer loans over bonds because under Indian accounting procedures, mark-to-market principles apply to their bond holdings – requiring them to write down the value of bonds when markets prices fall – and not to loans.30 The fact that corporate 11 bonds are subject to tax on delivery provisions and government securities are exempt biases investors in favor of the latter. When financial institutions invest in corporate bonds their buy and hold strategies limit the development of secondary markets. Individual investors in India strongly prefer fixed income assets where the principal is protected. The lack of liquidity in the secondary market raises risk to unacceptable levels for most of these investors. The risk adverse nature of investors and the risk magnification due to the underdeveloped secondary market has limited investment in the bonds of the largest and safest corporations. Reforms to improve the market design have been limited and where they have been implemented, traders have stubbornly stuck to pre-reform trading practices. In contrast to the reformed market design for equity and government securities, the corporate bond market has no centralized counter party for trades. Settlement takes place bilaterally among participants. The secondary market has no instruments for hedging. Issuers and investors cope with the risks presented by the underdeveloped nature of the secondary market by negotiating deals through private placement – direct bilateral negotiations between parties off the exchange. Private placement has the attraction of reducing risk because the two parties involved are known to each other. It also allows for deals to be fashioned to meet the distinct needs of buyers and sellers. Private placement takes less time, minimizes regulatory requirements, and is less costly than public issues. However, private placement is harmful to secondary market liquidity because deals are not standardized and involve smaller issues that fragment the market. Unless records of the deals are entered into a centralized database, it also interferes with price discovery. When the NSE was first established in 1994, its wholesale debt market offered an electronic trading system that was capable of collecting this data. The Bombay Stock Exchange also adopted such a system. However, neither has been widely used. In 2004, SEBI ordered that, with the exception of spot trades, all secondary market trading should be through the electronic order matching electronic systems provided by the exchanges. This has encouraged an increase in bilateral deals among financial institutions on the secondary market in order to avoid conducting trades through the stock markets. Even when broker members of the exchanges intermediate trading, they avoid reporting the transactions to the exchanges. SEBI’s efforts to move secondary market trading to the electronic trading systems of the exchanges has proved counterproductive.31 Impact of the Reforms We can see the impact of the reforms in the differential advances of the equity market compared to the markets for government. The reforms of India’s equity markets have produced remarkable results. From 1990 to 2005, market capitalization as a share of GDP – a key measure of market development – multiplied by more than five times from 12.2% to 68.6 %.32 As Figure 1 demonstrates, the increase in India’s equity market capitalization to GDP rate substantially outpaced the growth of the global average. In fact, it was greater than the average growth for all categories of countries – lower, middle, and high income. At the end of 2006, Indian market capitalization was $819 billion making it the 15th largest market in the world. Of all emerging markets, only China, Russia, and Korea had higher equity market capitalization.33 12 Figure 1: Market Capitalization as Percent of GDP: Country and Regional Averages 140 120 Percent of GDP 100 India Low Income Middle Income High Income World 80 60 40 20 0 1990 2000 2002 2003 2004 2005 Source: National Stock Exchange. Indian Securities Market: A Review Vol X Mumbai National Stock Echange of India Limited, 2007, p. 6. The introduction of the NSE with its electronic order-matching trading system and national satellite network led to a boom in trading. So did the development of webbased trading which by March 2007 had more 2.4 million users.34 Market turnover on India’s stock exchanges grew from Rs. 1.7 trillion in 1994-95 to Rs. 76.9 trillion in 200607. (See Figure 2) Internationally, India ranked 18 in terms of total value traded. Among developing countries, only China, Saudi Arabia, Korea, and Taiwan ranked ahead of it. In some ways, the number of trades processed is a better measure of the effectiveness of a trading system.35 On this measure, India’s National Stock Exchange ranked third in the world trailing only NASDAQ and the New York Stock Exchange. The Bombay Stock Exchange ranked sixth in the world.36 Not only have the number of transactions on the market proliferated, but the transaction costs have declined. In 1993, total transaction costs – including brokerage, market impact cost, and settlement costs – were 5 percent. By 2004, these costs have been reduced to 0.38 percent. Now, transaction costs on India’s equity markets are lower than on the New York Stock Exchange.37 Until June 2000, India had no derivatives market. It now has a diverse array of index and stock futures and options. By 2006, the National Stock Exchange ranked as fourth in terms of derivative trading among the world’s exchanges. It ranked first in terms of the trading of single stock futures.38 13 Figure 2: Growth of Turnover on Indian Equity Market, 1994-95 to 2006-07 in Rs. Billion 120000 100000 80000 60000 40000 20000 0 Rupees Billion 1994-95 1995-96 1996-97 1997-98 1998-99 1999-00 2000-01 2001-02 2002-03 2003-04 2004-05 2005-06 2006-07 1697 2376 6884 10,199 11,289 23,712 33,133 19,469 24,799 50,793 51,183 76,899 105,390 National Stock Exchange. Indian Securities Market Review Vols. 7 & 10, 2004, 2007, Mumbai: National Stock Exchange, 2004, 2007, pp. 11, 12. Finally, the nature of market participants has been transformed. Prior to the reforms, India’s stock markets were a closed club whose members exercised their monopoly over access to extract high fees and to control the exchanges and manipulate trading rules. At the beginning of the 1990s, India’s equity were dominated by the 550 brokers of the Bombay Stock Exchange, who controlled access to India’s most prestigious market and whose poorly capitalized owner-proprietorships and small partnerships prevented new firms from accessing the market. As of March 31, 2007, India had 9443 brokerages of which 4,110 (43.5 %) are corporately owned. Membership on the exchanges is now open as long as applicants can meet capital adequacy requirements.39 The importance of mutual funds has increased immensely. Until 1986, the public sector Unit Trust of India was India’s only mutual fund. By 2007, India had 40 mutual fund companies offering a wide range of investment opportunities. In 199091, India’s mutual funds mobilized Rs. 75 billion. In 2006-07, they mobilized Rs. 940 billion ($21.6 billion) and had an asset base of Rs 3.3 trillion ($74.8 billion).40 Until 1993, foreign investors were banned from having a direct presence in India’s financial markets. At the beginning of 2007, 1044 foreign institutional investors operated in India owning just less than $52 billion in investments.41 Not only are Indian equity markets increasingly attractive to foreign investors, but the services of Indian financial firms have become internationally competitive. This is most clearly manifest in the rapid growth of financial services outsourcing to India by financial leaders including Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanly, J.P. Morgan Deutsche Bank among others.42 India’s market for government securities has also experienced considerable development. Resource mobilization by government securities from India’s primary market has increased from Rs. 116 billion in 1990-91 to Rs. 2 trillion in 2006-07. (See 14 Figure 3) The total outstanding stock has grown 3.5 times from 1995 to June 2006. It now equals roughly 35% of GDP, roughly in line with that of Malaysia (40%), South Korea (30%), and China (slightly less than 30%).43 Transactions on the secondary market have also grown rapidly. From Rs. 295 billion in 1995-96, they increased to more than Rs.17 trillion in 2003-4. However, since 2003-4, they have declined to less than 4 trillion. (See Figure 4) Figure 3: Government Securities' Resource Mobilization from India's Primary Market, 1996-97 to 2006-07 in Rs. Billion 2,500 2,000 1,500 Rs. Billion 1,000 500 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Source: National Stock Exchange. Indian Securities Market: A Review Vol 10 2007 & Vol. 7 2004 Mumbai: National Stock Exchange Ltd., 2007, p. 9; 2004, p. 10. 15 Figure 4: India's Secondary Market Transactions in Government Securities: Total SGL NonRepo Turnover in Rs. Billion, 1995-2005-7 18000 16000 14000 12000 10000 Rupees Billion 8000 6000 4000 2000 0 Rupees Billion 1995-96 1996-97 1997-98 1998-99 1999-00 2000-01 2001-02 2002-03 2003-04 2004-05 2005-06 2006-07 295 939 1610 1875 4565 5721 12120 13924 17014 12609 7080 3983 National Stock Exchange. Indian Securities Market Review, Vol 10 2007. Mumbai: National Stock Exchange of India, 2007, p. 196 The secondary market for government securities still lack liquidity. This is in part a consequence of the fact that the RBI has fragmented the market by issuing many types of instruments in an effort to tap into isolated pockets of demand. It is also because primary market buyers, such as banks and insurance companies who are legally mandated to hold large numbers of securities, prefer to hold rather than sell. As a consequence of the low liquidity, the market for government securities market still lacks resilience. Susan Thomas finds that higher turnover is associated with higher returns. Turnover diminishes with declining returns.44 Even more importantly, an adequate benchmark yield curve has yet to emerge. This negatively affects other markets – such as the corporate debt market – that use the yield curve on “risk-free” sovereign bonds to price liquidity and risk premia on other financial instruments. It impeded the emergence of the “Bond-Currency-Derivatives (BCD) Nexus which helps to attract foreign investment and facilitates risk management strategy.45 Ultimately, a weak BCD nexus weakens “monetary policy transmission” or the effectiveness of monetary signals such as shortterm interest rate increases to induce the desired responses of economic actors. Weak monetary policy transmission necessitates larger changes in monetary policy to reduce inflation or stimulate the economy. In comparison with the equity and government debt market, India’s market for corporate debt lags far behind. While the capitalization of Indian private corporations was estimated to be 56% of GDP, private corporate debt raised on the debt market accounted for only 2% of GDP, by far the lowest of any of Asia’s emerging markets in Figure 5. The underdevelopment of India’s corporate debt market is also clear from the breakdown for the funding sources of private sector, non-financial firms over the period from 1990-91 to 2003-04.46 (Figure 6) Internal funds (retained earnings) and “Others” 16 (current liabilities and provisions) are the largest categories. Banks and financial institutions also provide substantial support. Funding from the debt market lags far behind at 4.8%. Figure 7 demonstrates a key explanation in the underdevelopment of India’s corporate debt market. Almost nine times as much corporate debt over the twelve year period from 1995-96 to 2006-07 was raised through private placements as was raised through public debt issues. In 2005-06 and 2006-07 no funds of significance were raised on the by public debt issues. Moreover, 81 percent of the funds raised from the corporate debt market over the ten year period from 1995-96 to 2004-2005 were raised by public sector enterprises. They have an easier time raising money because their debt qualifies is included among the public sector securities that banks, insurance companies, pensions, etc. are required to own The bonds of PSU’s also carry an implicit government guarantee.47 The number of private sector bond issues has steadily declined in recent years. (Figure 8) Of all outstanding issues of corporate bonds on August 25, 2005, more than 94% were rated AA or above.48 Investors discount the risk-reward matrix, and there is no junk bond market. The dramatic decline in the Indian corporate sector’s debt-equity ratio is one of the best indicators of the unevenness of India’s capital market reforms, though it is important to note that the figures for debt in the numerator overstate the importance of bonds since loans comprise most of the debt of Indian corporations. The debt-equity ratio declined from 1.82 in 1992-93 to 0.97 in 2004-05.49 The decline contrasts with the general increase in corporate debt financing in emerging markets. The failings of India’s corporate debt market can be seen in growth of India’s external commercial borrowing which facilitated by liberalizing policy measures has grown by an annual average rate of more than 49%.50 Figure 5: Comparative Depth of Equity and Corporate Debt Markets, Selected Countries 2004 80 Malaysia 70 S. Korea Private Corporate Debt Market/GDP 60 50 Japan Singapore 40 30 Thailand 20 Indonesia China 10 India 0 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 Private Equity Capitalization/GDP Source: Diana Farrell, Susan Lund and Leo Puri, “India’s financial system: More market, less government,” The McKinsey Quarterly (August 2006) p. 3. 180 17 Figure 6: Sources of Funding for India's Private Corporations, 1990-91 through 2003-04 Others (current liabilities & provisions), 26.30% Internal Sources, 33.10% Banks/Financial Institutions, 19% Equity Market, 16.10% Debt Market, 4.80% Source: Franklin Allen, Rajesh Chakrabarti, Sankar De, Jun qian, Meijun Qian, "Financing Firms in India," World Bank Policy Research Paper, 3975, 2006 Figure 7: Debt Funding for India's Corporate Sector, 1995-96 to 2006-07 (in Rs. Million) 1,000,000 900,000 800,000 700,000 600,000 500,000 400,000 300,000 200,000 100,000 0 Public Issued Debt 1995-96 1996-97 1997-98 1998-99 1999-00 2000-01 2001-02 2002-03 2003-04 2004-05 2005-06 2006-07 29,400 69,770 19,290 74,070 46,980 41,390 53,410 46,930 43,240 40,950 0 0 Pvt. Placement Debt 100,350 183,910 309,830 387,480 547,010 524,335 462,200 484,236 484,279 551,838 818,466 932,552 Source: National Stock Exchange. Indian Securities Market: A Review Vol. 10 2007. Mumbai: National Stock Exchange of India Ltd., 2006 p. 55. 18 Figure 8: Private Sector Bonds Through Private Placement: Number of Issues 1995-96 to 200506 140 126 120 111 111 100 100 96 95 79 80 56 60 43 40 20 15 0 1995-96 1996-97 1997-98 1998-99 1999-00 2000-01 2001-02 2002-03 2003-04 2005-06 Source: Report of High Level Expert Committee on Corporate Bonds and Securitization. Mumbai: 2005, p. 57. Explaining the Uneven Nature of India’s Capital Market Reform The Legal Origins Perspective The legal origins perspective proposes that legal systems originating with the common law tradition are more likely to develop a legal framework that supports efficient financial markets because the common law tradition facilitates judicial independence and flexibility to articulate pragmatic solutions to legal problems. Since the common law tradition is a dichotomous variable that is either present or absent in a country’s legal system, it is fundamentally ill-suited to explain the variation in outcomes across India’s capital markets. Furthermore, as Armour and Lele’s study of law and financial development in India shows, India’s judicial system with a backlog of 41,000 cases before the Supreme Court, nearly 4 million before the high courts, and some 25 million before the district courts is simply too slow to update laws to provide the support necessary for a dynamic economy.51 According to the World Bank, India ranks 177 of 180 countries with regard to the ease of contract enforcement, and bankruptcy proceedings regularly last ten years or more, with an average recovery rate of just 12 cents on the dollar.52 True, the case of India provides examples of the country’s independent judiciary providing a supportive legal framework for financial markets such as its fending off political interventions to weaken private property rights.53 But it is also true that India offers incidents that suggest that an independent judiciary can impede efforts to strengthen the capacity of creditors to enforce their claims such as when judicial acts delayed implementation of provisions in the Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act 1993 and the Securitization and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Act 2002. In sum, when we move from 19 the statistical relationships that support the legal origins perspective to study of the mechanisms that have promoted change (positive and negative) in Indian capital markets, there is little support for this approach. The Constructivist Crisis Perspective Thinking about the impact of crises on economic reform have come along way since Mancur Olson argued that exogenous economic shocks made radical reform possible by “clearing the deck” of sclerotic distributional coalitions.54 Drawing on the historic social science tradition that observes that the uncertainty caused by crises or “unsettled times” elevates the importance of ideas and ideology, the constructivist crisis perspective gives priority to the role of ideas in constructing interests and viable alternatives. “Even exogenous shocks must be endogenously interpreted” declare Widmaier, Blyth and Seabrooke.55 There is no gainsaying the prominence of economic crises in the reforms of India’s capital markets. The most important crisis – the $1.6 billion Harshad Mehta scam -- erupted in the spring of 1992. The roots of the crisis lie in the repressed nature of India’s financial system, in particular the requirement of banks to maintain remarkably high levels of their assets in the form of low yielding government securities at a time far higher returns could be earned on other markets, in particular, India’s stock markets. The difference in returns created powerful incentives – for banking officials and for stockbrokers alike -- to find ways to make low yielding funds deposited with bank available for high yielding investments in India’s stock markets. Some of the more unscrupulous brokerages, who were lightly capitalized partnerships, had an additional incentive. The shallowness of the market and the additional leverage provided by stock exchange’s badla system of finance, made it possible for bear and bull cartels to manipulate prices of particular equities. An important impetus for the scam began in 1986 when the government ordered that public sector enterprises raise funds from the bond market to replace the subsidies that it curtailed. By 1992, PSE bonds had raised more than $8 billion.56 Many of the sales were implemented through private placement which according to some reports involved an implicit deal. Banks purchased the bonds of a PSE on the condition that the PSE’s would deposit the funds and make additional deposits with them. The banks placed the funds into portfolio management schemes (PMSs) which guaranteed the PSE’s a return that was higher than the coupon rate of their bonds. The banks then invested the funds into equity markets where they earned an even higher return. It was at this point that brokers got into the act. They were eager access PMS funds so that they could invest in the seemingly endless market boom. In fact, some of the brokers were using the infusion of liquidity to drive up the prices of particular stocks. To this end, they availed themselves of badla the carry forward system of finance to increase their leverage. Realizing these returns necessitated that the banks circumvent regulations prohibiting them from making loans to brokers. The banks needed to conceal the leakage of these funds from the regulator, the Public Debt Office (PDO) of the RBI, which was responsible for operating a manual clearing and settlement system involving the manual recording banking transactions in subsidiary general ledgers (SGLs). There were often lengthy delays in recording transactions, and the banks began issuing bankers receipts (BRs) for the securities whose transfer was delayed in by the PDO. The PDO 20 and auditors lost track of the transactions. Many banks concealed diversion of funds to brokers by selling securities to another bank while issuing a BR instead of transferring the securities. Some banks issued fraudulent BR’s without entering into security transactions. Others simply turned their funds over to brokers for a lucrative fixed fee.57 After the scam was finally revealed, the RBI investigative committee report observed, “…the indiscriminate use of BRs without security backing created a kind of paper money which circulated from bank to bank like a stage army of solders and provided an opportunity to brokers to avail of funds of increasingly larger amounts.”58 The scam was finally revealed when a shortfall in the investment portfolio of the State Bank of India was revealed after a postponed settlement on the Bombay Stock Exchange made it impossible for a broker to meet his obligations with the bank. By any objective account the central cause of the scam lies with the banking sector and the pathetic supervision performed by the RBI. Why then did the scam give more impetus for reform of the equity market than the government securities market, and why did it lead to excessive regulation that impeded reform in the corporate bond market? The constructivist perspective provides some persuasive answers. Most of the information about the scam came from the RBI investigations. While these made the breakdown of the clearing system clear, they underscored the role of the brokers. The story was made more plausible by the larger than life image Harshad Mehta, the flamboyant broker, with fleet of Mercedes Benz, whose meteoric rise put him on the covers of India’s financial press. The RBI and the financial press constructed a narrative that resonated with the cynicism about brokers that was widely held among the public in a manner that is consistent with Seabrooke’s argument that elite elaborated narratives must resonate with popular values. Ultimately, only brokers and a few lower level banking officials were ever punished. By focusing the attention on the brokers and the stock markets it gave impetus to equity market reform. In the name of protecting investors, SEBI implemented strict requirements for listing and disclosure. Ironically, these requirements created the incentives that reinforced the preferences for private placement in the corporate debt market. The Political Power Approach But who constructed the narrative and did their interests influence their selection of the script? Information about the scam was largely revealed through investigations conducted by the RBI which worked closely with the Ministry of Finance. The central bank was in an awkward position since its inspectors had uncovered the banker-broker nexus as early as 1986, and yet it did nothing to curtail the fraud.59 It was not in the RBI’s interest to highlight its own regulatory failings. The central bank’s shareholding in many of the public sector banks gave 1in an interest in understating its role in the scandal. The scandal brought forth calls for Finance Minister Manmohan Singh’s resignation. Questions posed about the role of economic liberalization and the scam threatened to discredit the entire economic reform program. These circumstances created an elective affinity between the interests at stake of the most important actors and the narrative that they constructed. 21 The impact of the anti-broker narrative and the script for reform that ensued has its limits. It was certainly a contributing factor to the creation of the National Stock Exchange and the stream of equity market reforms that ensued. The narrative undermined the claim of the brokers that in view of their expert understanding of the market, the Ministry of Finance should leave the markets to alone. The availability of platforms for computerized trading and the Ministry of Finance’s growing awareness of international best practices in market design also motivated its officials, so when the broker dominated BSE resisted computerization, the Ministry of Finance supported the creation of the NSE as a public sector initiative. However, the impact of the crisis had it limits. Though the narrative made it clear that the badla carry forward system of finance was central to the broker’s speculative strategies and set the stage for SEBI’s decision to ban badla. SEBI was forced to lift the ban in the face of a declining market which the brokers claimed was due to the fact that the bear market was caused by the ban and the consequent decline in liquidity. It was only when the NSE had created the necessary market infrastructure to replace badla – the NDSL, the NCCSL, a market for derivatives that SEBI could effectively ban badla. It might be argued that those reforms implemented in the market for government securities were components of market infrastructure necessary for further reform. However, this position still can’t explain why India’s equity markets implemented similar market infrastructural reforms more rapidly. It also fails to explain why the Government of India has repeatedly delayed the implementation of key components of market design like a debt management office. Delays in the creation of a debt management office highlight the power of conservative elements within the Reserve Bank of India. As the Ministry of Finance’s Report of the Internal Working Group on Debt Management points out, the establishment of debt management offices that are separate from monetary policy authorities is an internally accepted best practice.60 The prolonged delay is all the more untenable in light of the potential contribution of a debt management office to eliminating RBI’s conflicts between managing the government’s debt (for which maintaining low interest rates and captive buyers is advantageous), managing its monetary policy (where interest rate flexibility is key), and regulating the promoting the development of debt markets and the banking sector (where it is desirable to end the financial institutions’ status as captive buyers and reduce their high reserve requirements). These advantages have been clear to a series of government authorities since the Ministry of Finance’s Report of the Internal Expert Group on the Need for a Middle Office for Public Debt Management in 2001. It has even been proposed by the Minister of Finance in his budget speech for 2006-07. And still the reform has yet to be implemented. Why have powerful sectors within the RBI remained conservative opponents of reform? In addition to the desire not to give up power, answers might be found in the central bank’s organizational history. After extensive state interventions in financial markets such as the 1969 Bank Nationalization Act and the 1974 Foreign Exchange Regulation Act the RBI grew to be the largest central bank in the world in terms of number of employees. Divisions such as the Exchange Control Department, the Banking Supervision Department have a deep-rooted distrust of markets.61 From the perspective 22 of many, it is one thing to liberalize equity markets where the costs of mistakes will be paid by the private sector. It is another to liberalize the market for government securities, where the costs will be paid by the state.62 Concluding Remarks This paper has conducted a qualitative comparative history of India’s capital market to examine the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches to capital market development. It has defined market narrowly so as to highlight the variation in market outcome. Examination of the mechanisms causing this variation has been central to evaluating the different theories of financial market change. The Legal Origins Perspective with its positing of a uniform causal mechanism for financial market development is ill-suited to explain variations of outcomes within the financial sector. The Constructivist Crisis Perspective illuminates an important aspect of the dynamics of change. The meaning of financial crisis of the spring of 1992 was endogenously constructed from a range of alternative narratives. The manner in which it was constructed gave impetus to reforms in the equity market even while it led to reforms that impeded the development of the market for corporate debt. But if crises do not come with pre-assigned meanings, the construction of crises does not take place in a vacuum. Ideas may shape interests in times of crises, but interests also shape the selection of ideas that are used to construct a narrative. It is dangerous to analyze the construction of narratives of meaning without considering who is doing the construction and why. The Political Power Perspective plays an important role even when crises elevate the role of ideas. At the same time, the interests of powerful actors are constructed as a legacy of previous policies and the world views that they perpetuate. 23 Endnotes Diana Farrell, Susan Lund, and Leo Puri, “”India’s financial system: More market, less government,” The McKinsey Quarterly (August 2006) p. 1. 1 Douglass C. North, “Markets and Other Allocation Systems in History: The Challenge of Karl Polanyi,” Journal of European Economic History 6 (1977) p. 710. 2 3 Douglass C. North, Understanding the Process of Institutional Change (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005); Douglass C. North Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990); Douglass C. North, Structure and Change in Economic History (New York: W.W. Norton, 1981; John McMillan, Reinventing the Bazaar: A Natural History of Markets (New York: W.W. Norton, 2002); and Avner Greif, Institutions and the Path to the Modern Economy: Lessons from Medieval Trade (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006). 4 For a review of this literature and its critics see Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, and Andrei Schliefer, “The Economic Consequences of Legal Origins,” Journal of Economic Literature 46:2 (2008) pp. 285-332. Seminal contributions include Thorsten Beck, Asli Demirguc-Kunt and Ross Levine, “Law and Finance: Why Does Legal Origin Matter?” Journal of Comparative Economics 31:4 (2003) pp. 653-75; Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de Silanes, Andrei Schleifer and Robert W Vishny “Legal Determinants of External Finance,” Journal of Finance 52 (1997) pp. 1131-1150; Rafael. La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de Silanes, Andrei Schleifer and Robert W. Vishny, “Law and Finance,” Journal of Political Economy 106 (1998) pp. 1113-1155. The term comes from Wesley W. Widmaier, Mark Blyth, and Leonard Seabrooke, “Exogenous Schocks or Endogenous Constructions? The Meanings of War and Crises,” International Studies Quarterly (2007) 51 pp. 747-759. Other key works include Wesley Widmaier, “The Social Construction of the Impossible Trinity: The Intersubjective Bases of Monetary Cooperation,” International Studies Quarterly 48:2 (2004); and Mark Blyth, Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002). 5 Douglass C. North and Barry Weingast, “Constitutions and Commitment: The Evolution of Institutions Governing Public Choice in Seventeenth Century England,” Journal of Economic History 49 (1989) pp. 803-32. 6 For instance, Stephen Haber, “Political Institutions and Financial Development: Evidence from the Political Economy of Bank Regulation in Mexico and the United States,” in Stephen Haber, Douglass C. North and Barry R. Weingast (eds.) Political Institutions and Financial Development (Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2008) pp. 10-59. 7 Philip Keefer, “Beyond Legal Origin and Checks and Balances: Political Credibility, Citizen Information, and Financial Sector Development,” in Stephen Haber, Douglass C. North and Barry R. Weingast (eds.) Political Institutions and Financial Development (Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2008) pp. 138. 8 9 Ibid., pp. 125-55. Raghuram G. Rajan and Luigi Zingales, “The Great Reversals: The Politics of Financial Development in the 20th Century,” Journal of Financial Economics 69 (2003) pp. 5-50; and Raghuram G. Rajan and Luigi Zingales, Saving Capitalism from the Capitalists (New York: Crown, 2003). 10 11 Saving Capitalism p. 139. Susan Thomas, “How the financial sector in India was reformed,” (Mumbai: Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Finance, 2005) p. 4. 12 24 13 “BSE resents order to increase membership,” The Economic Times (August 22, 1991). Susan Thomas, “How the financial sector in India was reformed,” (Mumbai: Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Finance, 2005) p. 4. 14 Lawrence Summers, Speech to the Conference on India’s Economic Reforms, Stanford University, June 2002. 15 16 In one notorious 1958 incident RBI Governor Rama Rau was obliged to resign after the Ministry of Finance informed him that his protests over government actions that effectively raised interest rates were unacceptable. On the lack of RBI independence see, Anand Chandavarkar, “Toward an Independent Federal Reserve Bank of India,” Economic and Political Weekly (August 27, 2005) pp. 3837-3845; Deena Khatkhake, “Reserve Bank of India: A Study in the Separation and Attrition of Powers,” in Public Institutions in India: Performance and Design New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2005 pp. 320-50. The term “captive market” was actually used by a high profile committee appointed by the government to review the monetary system. See Report of the Committee to Review the Working of the Money Market (Chakravarty Committee) Bombay: Reserve Bank of India, 1985) p.254. 17 18 Kunal Sen and Rajendra Vaidya. The Process of Financial Liberalization in India (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1997) pp. 16-17. Ajay Shah and Susan Thomas, “The evolution of the debt and equity markets in India,” unpublished paper, (Mumbai: Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, 2001), p. 6. 19 20 R.C. Murthy, The Fall of Angels New Delhi: Harper Collins, 1995, p. 20. 21 Kunal Sen and Rajendra Vaidya. The Process of Financial Liberalization in India (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1997) pp. 47-48. 22 The Financial System Report by M. Narasimham (reprint edition) (New Delhi: Nabhi, 1998) p. 10. Originally published by the Ministry of Finance, Government of India 1991. 23 Report of High Level Expert Committee on Corporate Bonds and Securitization (New Delhi: Ministry of Finance, Government of India, 2005) p. 9. Ajay Shah, “Flying on One Engine,” Pragati (August 2009) available at http://pragati.nationalinterest.in/2009/08/flying-on-one-engine/ accessed on March 7, 2010. 24 25 For a systematic comparison of the reformed SGL with the NSDL see Ajay Shah and Susan Thomas, “The evolution of the debt and equity markets in India,” unpublished paper, (Mumbai: Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, 2001), pp. 13-14. For a detailed description of the CCIL’s operations see R.H. Patel, “The Clearing Corporation of India” mimeo, n.d. 26 27 Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Government of India, Report of the Internal Working Group on Debt Management (New Delhi, 2008) p. 60. This estimate was made by the Government of India’s Committee on Infrastructure in a report released May 2007 as reported by Francesco Garzarelli, Sandra Lawson, Tushar Poddar and Pragyan Deb,”Bonding the BRICs: A Big Chance for India’s Debt Capital Market,” Goldman Sachs Global Economics Paper No. 161, November 7, 2007, p. 13. Accessed at <https:// portal. gs.com> on July 3, 2007. 28 25 This argument is put fort in Diana Farrell, Susan Lund, and Leo Puri, “India’s financial system; More market, less government,” The McKinsey Quarterly (August 2006) pp. 1-9. 29 30 This distinction will change as banks begin implementing RBI requirements to adopt Basel II norms. 31 Ibid., p. 60. 32 National Stock Exchange. Indian Securities Market: A Review Vol X 2007 (Mumbai: National Stock Exchange of India Limited, 2007, p. 6 33 Ibid., p. 141. 34 National Stock Exchange. Factbook 2007 (Mumbai: National Stock Exchange of India Limited, 2007) p. 38 . 35 National Stock Exchange. Indian Securities Market: A Review Vol X 2007 (Mumbai: National Stock Exchange of India Limited, 2007, p. 139 36 Government of India, Ministry of Finance. Economic Survey of India 2007-08, (New Delhi: Government Printing Office, 2008) p. 72. Susan Thomas, “How the financial sector in India was reformed,” (Mumbai: Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Finance, 2005) p. 12. 37 38 Reserve Bank of India. Report on Currency and Finance 2005-06 (Mumbai, Reserve Bank of India, 2007) pp. 264-65. 39 Securities and Exchange Board of India. Annual Report 2006-07, (Mumbai: Securities and Exchange Board of India, 2007) p. 75. 40 National Stock Exchange. Indian Securities Market: A Review Vol X 2007 (Mumbai: National Stock Exchange of India Limited, 2007, pp. 63, 86. 41 Government of India, Ministry of Finance. Economic Survey of India 2007-08, (New Delhi: Government Printing Office, 2008) p. 75; Securities and Exchange Board of India. Annual Report 2006-07, (Mumbai: Securities and Exchange Board of India, 2007) p. 66. Heather Timmons, “Cost-Cutting in New York, but a Boom in India,” The New York Times (August 11, 2008). 42 Jennifer Asuncion-Mund,”India’s capital markets: Unlocking the door to future growth,” Deutsch Bank Research February 14, 2007, pp. 4, 5. 43 Susan Thomas, “How the financial sector in India was reformed,” (Mumbai: Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Finance, 2005) pp. 29-31. 44 45 For official recognition of the importance of the BCD nexus see Planning Commission, Government of India, Draft Report of the Committee on Financial Sector Reforms (New Delhi, 2008); and Ministry of Finance, Government of India, Report of the High Powered Expert Committee on Making Mumbai and International Financial Centre (New Delhi, 2007). 46 Franklin Allen, Rajesh Chakrabarti, Sankar De, Jun Qian, Meijun Qian, “Financing Firms in India,” World Bank Policy Research Paper, 3975, 2006, p. 52. 26 47 Ibid 48 Report of High Level Expert Committee on Corporate Bonds and Securitization (New Delhi: Ministry of Finance, Government of India, 2005) p. 64. Susan Thomas, “How the financial sector in India was reformed,” (Mumbai: Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Finance, 2005) pp. 34-35. These figures represent the book values. Thomas argues that they are the best estimates since the illiquidity of corporate bonds makes it difficult to estimate their market value. She reports that when the market value of equity is used the shift is even greater, from 2.19 in 198990 to 0.36 in 2004-05. 49 50 Government of India, Ministry of Finance. Economic Survey of India 2008-09, (New Delhi: Government Printing Office, 2008) p. 136. John Armour and Priya Lele, “Law, Finance, and Politics: The Case of India,” ECGI Law Working Paper No. 107/2008, 2008 available at <www.ecgi.org/wp>, accessed on June 24, 2008. 51 52 Cited in Garzarelli, et al, p. 9. 53 Lloyd I. Rudolph and Susanne H. Rudolph, In Pursuit of Lakshmi (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985). 54 Mancur Olson, The Rise and Decline of Great Nations (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982). Wesley W. Widmaier, Mark Blyth, and Leonard Seabrooke, “Exogenous Schocks or Endogenous Constructions? The Meanings of War and Crises,” International Studies Quarterly (2007) 51 p. 749. 55 56 Dilip Mookherjee, The Crisis in Government Accountability (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 144. 57 The best book-length accounts of the scam are Debashis Basu and Sucheta Dalal, The Scam: Who Won, Who Lost, Who Got Away (revised) (Mumbai: Kensource, 2001[1993]; and R.C. Murthy, The Fall of Angels (New Delhi: Harper Collins, 1995). 58 Report of the Committee to Enquire into Securities Transactions of Banks and Financail Institutions (Janakiraman Committee, Reserve Bank of India, Mumbai 1993, p. 277 as cited in Dilip Mookherjee, The Crisis in Government Accountability (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 146. 59 Debashis Basu and Sucheta Dalal, The Scam: Who Won, Who Lost, Who Got Away (revised) (Mumbai: Kensource, 2001[1993] p. 227-228. Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Government of India, “Report of the Internal working Group on Debt Management,” (New Delhi, 2008) p. 13. 60 61 62 Thanks to Jayant Varma who suggested this insight in an interview in Ahmedabad on January 13, 2010. This point was related to me by Joydeep Mukherjee of Standard and Poor, December 2, 2008.