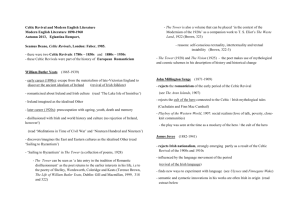

THE HISTORY OF CELTIC SCHOLARSHIP IN

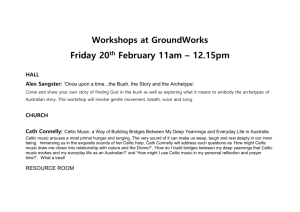

advertisement