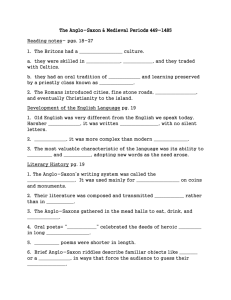

Oxen in place names and legal system

advertisement

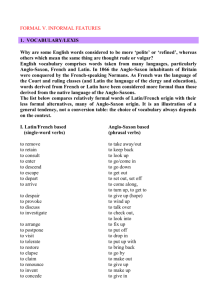

Ilmar Üle From Horsa to my grandmother, thoughts, facts, and ideas about the animal-related notions in Anglo-Saxon context In this rather loose-structured piece of writing I am trying to put down my thoughts and ideas of animals, English nouns they are and were called with, and any interesting notion I have been able to notice or to think of. In a way it is a ‘stream-of-consciousness’ type of writing. Being a student of Old English, I spent some time studying the linguistic, cultural, and social relevance of animals in the early English society and linguistic environment. I have not been trying to compile a scientific article, nor a proper essay. But it was interesting to write it, and I still have some hope that some people may find it interesting to read. The language and the time The Anglo-Saxon period lasted from the fifth century until the second half of the eleventh century. The language spoken during that period is the Old English. Scholars place Old English in the Anglo-Frisian group of West Germanic languages. It was quite different from the contemporary English, somewhat similar to Old Icelandic, Old Norse and the Gothic languages. In many aspects, the present day German resembles Old English to a much greater extent than present day English. The most widely recognised date of the beginning of the Anglo-Saxon period in England would be 410 AD, as this is the year the Roman army departed from Britain; and the period is considered to end on the 14th of October 1066, when the battle of Hastings was fought between the forces of Harold Godwinson and the Duke of Normandy. This ended the reign of the last Anglo-Saxon king. The course of battle is recorded in various Old English manuscripts, mainly the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the Bayeux tapestry. The latter one is a medieval embroidery depicting the course of the battle, thus being a valuable source of history as well as a remarkable piece of art. 1066 and the horse It is quite interesting to observe the two armies’ relation to and use of the horse. The concept of actually using the horse in a battle seems to have been totally alien to the Saxons. Horses were used primarily as beasts of burden and for transport to and from battles. It was normal, and was probably practised at Hastings, that the Saxon horses were dismounted and led away from the scene prior to the conflict. 1 The Norman's had a completely different approach to the horse. It became a fundamental part of their battle tactics. It is thought that many of the tactics used by the Norman's were still being practised right up until the end of the 19th century. As a student of Old English it is my opinion that it was the cavalry tactics of the Normans which led to the “breaking the backbone” of the language. By this expression I mean that if such basic words as ‘dale’ and ‘woods’ became replaced by loaned ‘valley’ and ‘forest’, the shift in the linguistic environment must have been enormous. The extensive use of cavalry in this battle finally led to the seventy per cent of French loans in English language as we know it today, it eliminated the West-Saxon dialect’s supreme position as a well established written language. And this resulted in other dialects getting their chance, as the following centuries witnessed the emergence of the Middle English dialects and Chaucer, and finally, Modern English, London speech, and Shakespeare. Oxen in place names and legal system What is the connection between Oxford and Bosporus? At first glance, nothing. I have never heard of ‘the University of Bosporus’ or the ‘strait of Oxford’. It may sound surprising, but ‘Oxenford1’ means the same as ‘Bos Porus’, literally shallow water that is no trouble for big animals, such as the ox, to cross. Little is known about the etymology of Oxford, but as it is situated at the banks of river Thames, it may as well be that nearby was a suitable place for crossing the stream; whereas Bosporus is traditionally connected with the legendary figure of Io, who in the form of an ox crossed the Bosporus in her wanderings. Leaving aside the Greek mythology and returning to the misty Albion of early times, one might wonder, what the people of that time thought of animals, for example, the ox, the sheep, or the horse. What was the value of a beast? Were they thought to be creatures with mind or soul? Were they considered to be responsible for their own deeds? In order to get a glimpse into the minds of the Anglo-Saxons, another source of information – lawcodes issued by the ancient British kings – comes to be of invaluable assistance. Issuing laws was the sole right of a king. Literally, this was about the only quality that differentiated the king from noblemen of other ranks. Through its sentence structure and expressions the early Anglo-Saxon law betrays its verbal origin and tends to make a much better reading than the fuzzy wordpiles of the contemporary laws. 1 Possible Old English scribal variations include Oxnaford, Oxonford, Oxenford, Oxneford, etc. 2 So, what about the ox? From the Ordinance respecting the 'Dun-Setas'2 we find out that an ox should be paid for 30 pence, whereas the price of a horse is 30 shillings. The price of man is a pound. After the Norman Conquest the pound was divided for accounting purposes into 20 shillings and into 240 pennies, or pence; there is little actual evidence about the value of coins from the earlier period. But what seems to be certain is that a good horse tended to be of greater value than an average slave, not mentioning the ox. Was it due to the practical value of the animal or prestige, is a good topic for further study. It is sure that a horse was a very valuable piece of property during that period, one might speculate, that this might have been one of the reasons the British warriors did not want to take the animals to battle. But of course, this seems a little too far-fetched conclusion and has to be treated with caution. Gif hwa forstele oðres oxan & hine ofslea oððe bebycgge, selle twegen wið & feower sceap wið anum. Gif he næbbe hwæt he selle, sie he self beboht wið ðam fio3. Yes, this is the everchanging English language. The text is a law issued by a ruler many consider the greatest British king of all: Alfred the king of Wessex (871–899). In this somewhat ambiguous code, a man is of equal value with two oxen or four sheep. In this particular case, the value of oxen seems a little too high; perhaps it was meant to be a harsh and unfair punishment for the unjust deed of stealing and failure to follow the Ten Commandments. Another code by Alfred the Great: If an ox gore a man or a woman, so that they die, let it be stoned, and let not its flesh be eaten. The lord shall not be liable, if the ox were wont to push with its horns for two or three days before, and the lord knew it not; but if he knew it, and he would not shut it in, and it then shall have slain a man or a woman, let it be stoned; and let the lord be slain, or the man be paid for, as the 'witan4' decree to be right. So, the beast is to pay for its deeds. This indicates that the Anglo-Saxons considered oxen to be animals with mind and free will, perhaps even soul. This particular fact, along with the price calculations of man and horse, seem to support the idea that in the minds of the AngloSaxons the humans and animals were not so very different at all. Although during that time Britain had already been christianised for quite a few centuries, the Christian ideas of all animals existing just for the benefit of humans seems to be not so widespread as one might have expected. For it was only a few centuries earlier when the legendary brothers Hengest and Horsa landed at Ebbsfleet thus starting the Anglo-Saxon colonisation of Britain. The 2 LawDuns (7), B14.31, 11th century, the code regulated the order of village council as well as everyday issues. 3 If any one steal another's ox, and slay or sell it, let him give two for it; and four sheep for one. If he have not what he may give, be he himself sold for the cattle. B14.4.3 Alfred-Ine (Introduction to Alfred). 4 also called Witenagemot, the council of the Anglo-Saxon kings. 3 famous Horse-named leader and his brother were definitely not Christian and their way of thinking seems to have been prominent even four hundred years later. The ox was also used to measure the land. In the area of Danelaw (the northern, central, and eastern region of Anglo-Saxon England colonised by invading Danish armies in the late 9th century), the basic unit of land measurement was ‘carucate’, which was the area an eight-oxen team could plough in a day. A very practical and quite precise way of measuring the land without employing mathematicians. The linking words The terms denoting animals or the ‘names’ for them seem to be among the linguistically most conservative ones, retaining their original forms even when the whole language around them has gone through major changes. Oxoxen, sheep (singular)sheep (plural), goosegeese. What might be the reason behind the irregularities? ‘Ox’, as well as ’child’ has simply retained its original plural form and nowadays it seems a little awkward. But this is the Old English background that shines through a millennium of constantly changing linguistic environment. The word ‘geese’ is a good example of Old English way of forming the plural through a phonetic device called the ‘i-mutation’. ‘O’, being a formed at the back part of the mouth, is changed to ‘e’, formed at the front of the mouth. The plural of ‘sheep’ is formed in a similar way, although the pronunciation does not change. The reason for this ‘zero change’ is the fact, that one possibly could not produce a sound in more front part of the mouth that it is already done when uttering ‘e’. Theoretically, the i-mutation is still there in ‘sheep’, although it is undetectable. Loanwords are an interesting field of study. Loans indicate cultural contacts between nationalities, cultures, and languages. They indicate the nature of the contacts, e.g. the subject of trade. If starting to pursue the origins of many words in everyday use of our present day language, on may come to interesting findings. What everyday word indicates the Finnish/Estonian contacts with the Roman Empire? ‘Raha’! The present day meaning ‘money’ has gone through a slight semantic change. The original form of this word is ‘skraha’, meaning ‘fur’ in the Visigothic language, which is has been extinct for about 1600 years. As the Finno-Ugric languages did not tolerate double initial consonants, the ‘s’ was dropped and the result was ‘raha’. The gothic traders, who have left their traces in placenames such as ‘Göteborg’ or ‘Gotland’, were interested in receiving furs in exchange for their weapons and jewellery of Roman origin. A similar phenomenon is illustrated by the Komi language, where the word ‘ur’ still denotes squirrel skin AND a coin of five kopecks. ...and the venom toads shall devour your flesh… 4 As small as the contemporary peoples’ knowledge of animals may be, it seems to have been somewhat worse in the 16th-17th century. Namely, Shakespeare writes about the ‘venom toads’. Toads were thought to be poisonous long time before Shakespeare, an especially cruel Anglo-Saxon nobleman is said to have thrown people into a dungeon full of ‘pades’, toads. Whether this kind of punishment was fatal, remains unknown. I would like to conclude my train of thought by an interesting example of a loan. The Old English word ‘pade’ reveals yet another Finno-Ugric - Anglo-Saxon contact. Namely, I remember my grandmother using the word ‘padakonn’ instead of the proper Estonian ‘kärnkonn’. There it is. An Estonian Midland dialect speaker using the lexemes of the WestSaxon dialect. It’s a small world. 5