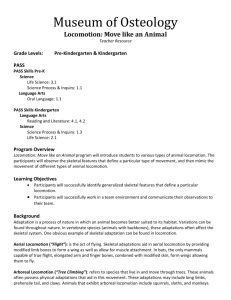

Assessment and locomotion together form part and parcel of

advertisement