Chek, Tom - Cengage Learning

advertisement

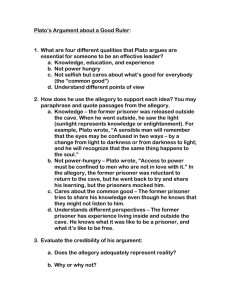

Chek 1 Prompt 1: Plot Compare the 1999 film, The Matrix with Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave.” In what ways does the plot of The Matrix echo the lesson Plato is teaching in the allegory? What do they both say about the human condition? Tom Chek Professor Wheeler EN 101 November 18, 2007 Mythic Narrative and The Matrix At first, the Wachowski brothers’ 1999 film The Matrix appears to be about the rise of an ordinary man into the role of savior of humanity; however, it is more interestingly about the journey of mankind to fulfill archetypes found in comparative religion and culture as described by Joseph Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, and Plato in his “Allegory of the Cave.” Although The Matrix explores many concurrently running themes throughout the film, the theme of the unwilling hero who embarks on a quest towards enlightenment, discovers his true potential, and returns to enlighten others, figures prominently into the plot narrative. Joseph Campbell, noted scholar on mythology, labels this type of journey a “hero-quest.” The heroquest is argued by Campbell to be an important universal pattern of mythic narratives and the film’s adherence to such patterns may explain its resonance with viewers and its popularity. Campbell articulates that all hero-quests intrinsically involve three stages: separation, initiation, and return. These three stages are echoed clearly within the film. Neo’s separation begins when he is mysteriously awakened by a cryptic message flashing on his computer screen instructing him to “follow the white rabbit.” Moments later, there is a knock at the door where he meets and makes an exchange with one of his illegal software clients. He notices a tattoo of a Chek 2 white rabbit on the shoulder of one of the women and accepts an invitation to a dance club where he meets the infamous hacker Trinity, who piques his interest. Here, we have a mysterious figure initiating the request that Neo separate from his world and take part in some sort of heroic journey (Stroud 428). “I know why you are here, Neo. I know why you hardly sleep…why night after night you sit at your computer. You’re looking for him…I was once looking for the same thing. And when he found me, he told me I really wasn’t looking for him. I was looking for an answer. You know the question just as I did. The answer is out there, Neo. It’s looking for you. And it will find you, if you want it to.” Trinity asserts that they share a common search for truth and conveys that Neo can unlock that truth if he so chooses. Once Neo embarks on his hero-quest, he embarks on an epic adventure. Campbell has found that this stage is marked by tests of character in which the hero is often aided by magical forces, and eventually a supreme ordeal. Once the hero overcomes the ordeal, triumph is often represented as “the hero’s sexual union with the goddess-mother of the world (sacred marriage), his recognition by the father-creator (father atonement), [or] his own divinization (apotheosis) (246).” As the film progresses, we see that the story arc of the film closely follows Campbell’s model in all of these aspects. Neo’s initiation takes place in a pivotal scene where Morpheus (whose moniker incidentally is that of the Greek god of dreams and transformation), presents Neo with a choice – the first test of his worthiness. Morpheus offers Neo a blue pill, which would leave him in the blissful ignorance of the Matrix simulation, or a red pill, which will awaken Neo to the true nature of the Matrix and human existence. Essentially, Neo must decide whether or not he wants to see the real world for himself. Neo chooses the path of reality and discovers that the real world is a stark contrast to that of the artificial construct of the Matrix. He becomes fully aware Chek 3 of the Matrix’s illusions and begins to exist in the real world. Neo’s second “test” occurs when he encounters the mysterious agents who attempt to thwart his quest for illumination. The agents can be seen as the “threshold guardians,” whom Campbell tells us, typically guard the doorways to adventure. Morpheus indicates that they are “Sentient programs…they are the gatekeepers of the Matrix. They are guarding all the doors. They are holding all the keys, which mean that sooner or later, someone is going to have to fight them.” This leads Neo to consult with the Oracle, a “magical helper” of sorts who offers Neo prophecies which will aid him in his quest. Morpheus fulfills the archetypal role of a father figure to Neo, preparing his mind and training him in the task of finding the power within himself. Throughout the entire film, Morpheus believes in Neo as the chosen one and has the utmost faith in him. Neo rewards Morpheus’ faith by following the destined path and emerging as a hero. We also see the “sacred marriage” in Neo’s love for Trinity. Trinity is a goddess figure in this quest, and without her love Neo would fail. Trinity was told by the Oracle that she will fall in love with the savior, The One. Neo became The One because she loved him. Were it not for her love, he would have died while plugged into the Matrix as the body cannot survive without the mind. It is Trinity who professes her love for him and resurrects Neo with a kiss. Neo is resurrected physically and existentially. Suddenly, all becomes clear to him and to him alone. He recognizes the Matrix as an illusion, and that as a result, his death is an illusion. Neo’s death is his final test, the ultimate ordeal. Once he has transcended death, he ultimately reaches deification or “apotheosis.” The film culminates with Neo becoming a virtual god-like divinity that is able to fly in the computer-generated world of the Matrix, stop bullets at will and read the Matrix’s computer code. Neo returns to the Matrix in an attempt to crash the system and restore society. Campbell Chek 4 argues that this return is the last precept of the traditional hero-quest in which the hero must return and use his newfound “boon” or “elixir” to free society from illusion (Campbell 216). The point of the great myths, including The Matrix, is to shed light on the human condition. We see this in Plato’s classic story “The Allegory of the Cave” and it is paralleled in The Matrix. In the Allegory of the Cave,” Plato describes prisoners chained in a cave, unable to turn their heads. All they can see is the wall of the cave. Behind them burns a fire. Between the fire and the prisoners there is a walkway, along which men walk carrying objects that cast shadows on the wall of the cave. The prisoners are unable to see these real objects that pass behind them. What the prisoners see instead are shadows cast by objects that they do not see. If a prisoner was to break free from his chains and turn to see the fire or objects, he would become illuminated to his condition in the cave. Furthermore, if the prisoner were to ascend out of the cave and observe the sun, shadows, and reflections, he would be enlightened to the true nature of reality. The importance of the allegory lies in Plato's belief that there are invisible truths lying under the apparent surface of things which only the most enlightened can grasp. Accustomed to the world of illusion in the cave, the prisoners will at first resist enlightenment, but those who can achieve enlightenment become rulers or heroes, and should take on the moral obligation of returning to the darkness to enlighten others. There are striking similarities in Plato’s story and Neo’s story. Neo’s world was an artificial construct created by the machines to enslave humanity much as Plato’s hero is bonded by chains from infancy and forced to observe shadows projected onto the cave walls. Neither is observing the true ideal form, only a facade. Morpheus explains the Matrix to Neo as “the world that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you from the truth…that you are a slave, Neo. Like everyone else, you were born into bondage, born into a prison that you cannot smell or taste or Chek 5 touch, a prison for your mind.” The symbolism of prisons is found in both stories, highlighting the fact that neither the people in the Matrix nor the people in Plato’s cave are truly free. To be free, Plato argues that it is not enough to rely solely on your physical senses, which can be deceived; one must also learn to see with the mind’s eye as well. In the scene immediately after Neo is unplugged from the Matrix, he questions, “Why do my eyes hurt?” Morpheus replies, “You’ve never used them before.” Plato states that “bewilderments of the eyes arise from two causes, either from coming out of the light or from going into the light, which is true of the mind’s eye, quite as much as of the bodily eye.” Plato argues that once man has seen the light, the truth, the good, it is only then can he know the difference between the light of the fire and that of the sun. Similarly, Neo can only distinguish the simulated reality of the Matrix with that of his true reality after being “unplugged” and educated by those who ascended before him. Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and The Matrix urge us to discern reality from the artificial – to strive for the pure form – to seek truth. It is through this questioning that the greatest truth, self-knowledge, can be attained. As much as the film stands on its own as a science-fiction tale mixed with intellectual and philosophical ideas, the directors have seemingly crafted the film to be ambiguous. Perhaps it is intended it to be a Socratic gadfly urging the viewer to reassess his or her search for identity and meaning. The fact that these views are disseminated crossculturally throughout the world and cut across multiple disciplines, including mythology, religion, philosophy, psychology, as well as contemporary cinema, bolsters the claim that humankind’s journey for truth, education, and self-understanding is an innate and timeless quest. The message imparted is that appearances are deceiving and that there is something deeper to be found in life. We have a choice to seek authenticity and truth, although it often requires giving up a level of comfort and familiarity. Like the Allegory of the Cave, The Matrix Chek 6 dramatically conveys the view that ordinary appearances do not depict true reality and that gaining truth changes one’s life and obligates one to help others. The role of the hero is to achieve a higher level of consciousness, past ignorance. John Partridge writes, “Transcending this state is the aim of genuine education, conceived as a release from imprisonment, a turning or reorientation of one’s whole life, an upward journey from darkness into light” (Partridge). In essence, Neo’s journey is our own. We each are on personal hero-quests, striving for truth and wisdom and in passing life’s tests and ordeals; we mirror the mythological archetypes and become heroes ourselves. Chek 7 Works Cited Campbell, Joseph. The hero with a thousand faces. New York: Princeton University Press. 1973 Lawrence, Matthew. Email correspondence. 15 February 2007. The Matrix. Dir. Andy and Larry Wachowski. With Keanu Reeves and Laurence Fishburne. 1999.VHS. Warner Bros. Partridge, John. “Plato’s Cave and The Matrix.” 2003. 31 October 2006 <http://whatisthematrix.warnerbros.com/rl_cmp/new_phil_partridge.html>. Plato. “The Allegory of the Cave.” Juxtapositions: Ideas For College Writers. Ed. Marlene Clark. Boston: Pearson Custom Publishing, 2005. 217-224. Scott R. Stroud. “Technology and mythic narrative: The Matrix as technological hero-quest.” Western Journal of Communication 65.4 (2001): 416-441. Wachowski, Andy & Larry. (1999) The Matrix (screenplay) 31 October 2006 <http://www.screenplay.com/downloads/scripts/The%20Matrix.pdf>.