Chest Pain

advertisement

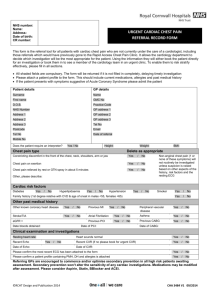

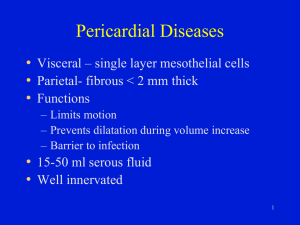

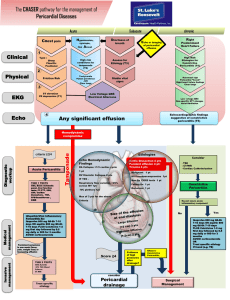

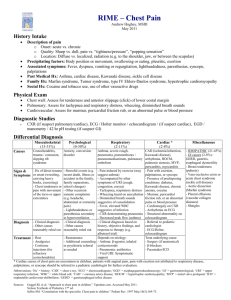

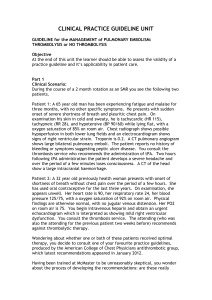

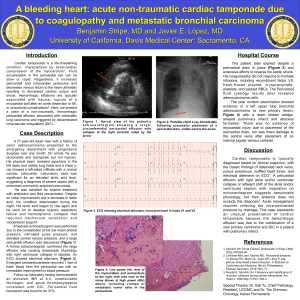

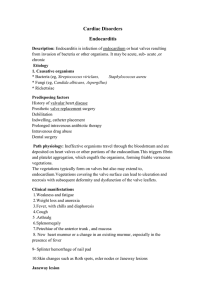

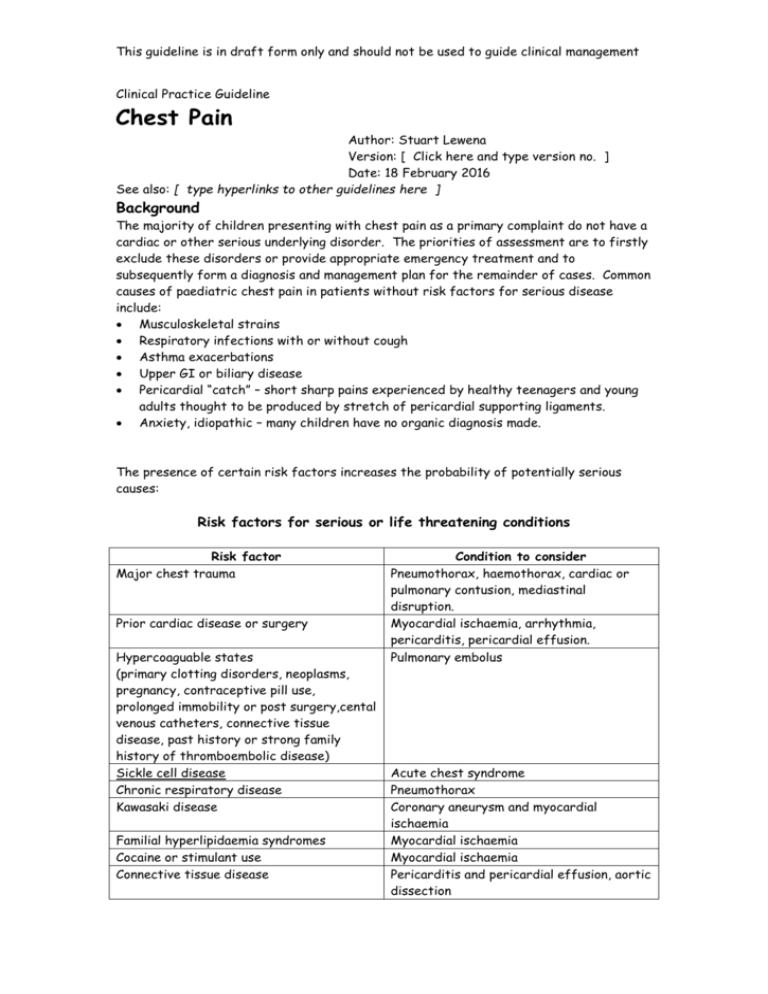

This guideline is in draft form only and should not be used to guide clinical management Clinical Practice Guideline Chest Pain Author: Stuart Lewena Version: [ Click here and type version no. ] Date: 18 February 2016 See also: [ type hyperlinks to other guidelines here ] Background The majority of children presenting with chest pain as a primary complaint do not have a cardiac or other serious underlying disorder. The priorities of assessment are to firstly exclude these disorders or provide appropriate emergency treatment and to subsequently form a diagnosis and management plan for the remainder of cases. Common causes of paediatric chest pain in patients without risk factors for serious disease include: Musculoskeletal strains Respiratory infections with or without cough Asthma exacerbations Upper GI or biliary disease Pericardial “catch” – short sharp pains experienced by healthy teenagers and young adults thought to be produced by stretch of pericardial supporting ligaments. Anxiety, idiopathic – many children have no organic diagnosis made. The presence of certain risk factors increases the probability of potentially serious causes: Risk factors for serious or life threatening conditions Risk factor Major chest trauma Prior cardiac disease or surgery Hypercoaguable states (primary clotting disorders, neoplasms, pregnancy, contraceptive pill use, prolonged immobility or post surgery,cental venous catheters, connective tissue disease, past history or strong family history of thromboembolic disease) Sickle cell disease Chronic respiratory disease Kawasaki disease Familial hyperlipidaemia syndromes Cocaine or stimulant use Connective tissue disease Condition to consider Pneumothorax, haemothorax, cardiac or pulmonary contusion, mediastinal disruption. Myocardial ischaemia, arrhythmia, pericarditis, pericardial effusion. Pulmonary embolus Acute chest syndrome Pneumothorax Coronary aneurysm and myocardial ischaemia Myocardial ischaemia Myocardial ischaemia Pericarditis and pericardial effusion, aortic dissection This guideline is in draft form only and should not be used to guide clinical management Assessment The most important step in initial assessment is identifying signs of cardiorespiratory distress: Dyspnoea, tachypnoea, increased work of breathing Hypoxia Abnormal pulse or blood pressure Poor perfusion Distended neck veins, muffled heart sounds Depressed mental state For further specific assessment of underlying cause see chest pain algorithm. Key examination and basic investigation findings that may be identified in uncommon serious conditions are presented in the table below: Condition Myocardial ischaemia Pericarditis Pericardial effusion Pulmonary embolus Aortic dissection Findings Abnormal pulse or blood pressure, arrhythmia, ST segment elevation or depression, raised troponins Positional pain, pericardial rub, widespread ‘saddle-shaped’ ST elevation Hypotension, distended neck veins, muffled heart sounds, pulsus paradoxus, globular enlarged cardiac silhouette on CXR Tachypnoea, tachycardia, hypoxia, haemoptysis, non specific ST and T wave changes in anterior chest leads most common ECG finding, ‘classical’ S1Q3T3 pattern is uncommon. May see minor CXR abnormalities – usually normal Differential limb BP’s, CXR findings include: widened mediastinum, left pleural cap and deviated trachea and main stem bronchi. Signs of myocardial ischaemia or pericardial tamponade if complicated by these events. Management Trauma patients and those with signs of cardiorespiratory compromise should be resuscitated along general principles prior to considering more directed management (see resuscitation guideline). Chest pain algorithm provides a guide for further management including special investigations, consultation and referral. All patients with positive risk factors for serious conditions should be discussed with senior staff prior to final disposition. Despite the rarity of serious underlying conditions, many children and parents have significant anxiety surrounding possible cardiac disease. Specific reassurance is an important part of management. This guideline is in draft form only and should not be used to guide clinical management