Dialogues

advertisement

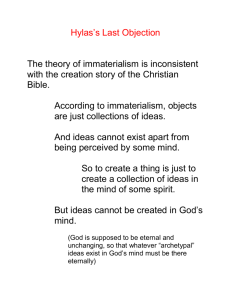

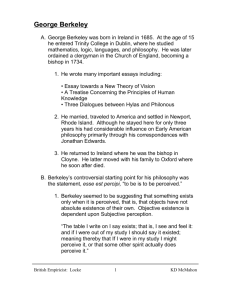

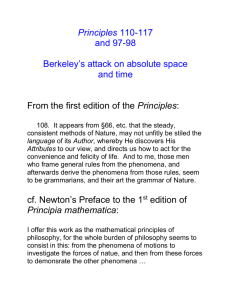

The Topics of the Dialogues Dialogues I & II: Arguments against materialism matter is unknowable and impossible Dialogues III: Presentation of the theory of immaterialism and defence of the theory against objections Immaterialism There are two kinds of things in existence: Ideas (inactive, perceived things) Minds (active, perceiving things) Extension, colour, pain are all ideas. (this has already been proven) Minds can be nothing like ideas and so must be unextended, and hence indivisible and naturally immortal. Immaterialism, cont.’d Ideas are of two kinds: Ideas of sense (vivid, involuntary, orderly ideas) Ideas of imagination (faint, voluntary, random ideas) Immaterialism, cont.’d There are also two kinds of language: ordinary language philosophical language The ordinary language terms “body” “material being” “real thing,” etc. Name the same things that, in philosophical language, are called “collections of ideas of sense, commonly observed to go together and referred to by a common name” The philosophical language terms “body” “material being” “real thing,” etc. name nothing whatsoever that anyone can perceive or in any way come to know, and nothing whatsoever that anyone can even conceive (insofar as they do name something conceivable, e.g., mind-independent, extended, solid, movable stuff, they name something that cannot possibly exist) What in ordinary language are called fictional or unreal things (“chimeras”) are either: ideas of imagination or: false inferences False inference Real things = collections of ideas of sense are not just collections of ideas coming simultaneously from different senses. The collections include different ideas coming from the same sense at different times. e.g., visual ideas of “the same object” (the same named collection of ideas) viewed from different distances Not all the members of a collection are perceived at once. Those that are perceived serve as signs for those that might be perceived later. Perceptual errors are not the result of perceiving unreal ideas of sense (all ideas of sense are equally real) but rather drawing the wrong conclusions about what other ideas are included in the bundle. (When this happens we form ideas of imagination that we take to be images of ideas of sense we will get later, but that do not correspond to later ideas of sense.) Immaterialism, cont.’d Because ideas are inactive, they cannot cause one another. (The only cause of ideas is minds, and it is not the business of natural science to study minds.) The job of natural science is to describe the ways in which ideas of sense are ordered. and, as far as possible, to show how specific ways in which ideas are ordered are merely instances of more general regularities in the succession of ideas An event is “explained” scientifically by showing how it follows from antecedent events in accord with a rule, how that rule is an instance of a more general rule, etc. Immaterialism, cont.’d There can be no true causality without activity, no activity without will, no will without volition, no volition without mind. I obtain direct, intuitive, non-ideational, “notional” knowledge of the existence of my own mind as an active, willing thing through “reflection.” This reflection tells me that I cause ideas of imagination through acts of will. Immaterialism, cont.’d I infer the existence of other minds by reasoning from the existence of ideas of sense, as effects, to the only cause I can conceive of. (and infer the existence of other ideas of sense and imagination perceived by those minds) I cannot infer the existence of a material substratum for qualities of extension and solidity in this same way. because nothing gives me any notion of matter because what I am told about it (that it is an inert, unthinking thing in which ideas inhere) makes no sense inherence of ideas in an unthinking substance makes no sense causation of ideas by what is without volition or will makes no sense In contrast, perception of ideas by a thinking subject does make sense, as does production of ideas by volition of an active subject Immaterialism, cont.’d Ideas cannot exist apart from being perceived. The “perceives” relation that obtains between minds and ideas is unique. In particular, it is not to be confused with the “contains” relation or the “inheres in” relation. Consequences of Immaterialism There is no distinction between appearance and reality. “… real things are those very things I see and feel and perceive by my senses.” (misperception is explained as above) Those who draw a distinction between material and sensible things, and who take the material things to be real and the sensible things to be appearances are forced to: deny that we can know anything about real things contradict common sense affirm that it is impossible that any real, corporeal thing could exist Consequences of Immaterialism, cont.’d There is no distinction between primary and secondary qualities. Real things are collections of ideas perceived by the senses. These collections include ideas of colours and other sensible qualities as well as ideas of extension, solidity, and their modes (The two are in fact inseparable) Consequences of Immaterialism, cont.’d There is no distinction between the existence of a real thing and its being perceived. Because real things are just collections of ideas perceived by the senses. And for an idea to exist is for it to be perceived. For a real thing to exist unperceived can only mean that it is perceived by some other mind when it is not being perceived by me Or perceived by a divine mind when there is no finite spirit around to perceive it In ordinary language, what it means to say: “an object exists” is that an object is perceived “an object does not exist” is that an object is not perceived “an object exists away from me” is that that object is perceived by some other spirit “an object exists where there is no finite spirit around to perceive it” is that that object is perceived by God (though ordinary people may not pause to reflect on the fact, their belief in the existence of objects in uninhabited regions is bound up with a belief in the omnipresence of a divine perceiver — only heathens and atheists attempt to think otherwise by inventing the notion of matter) Berkeley’s Argument for the Existence of God Sensible things are independent of my mind So they have an existence exterior to my mind. So there is some other mind in which they exist. But sensible things have an existence exterior to all finite, created minds. So there must be an omnipresent, external mind which perceives all things and exhibits them to our view in accord with the laws of nature. Hylas’s Most Serious Objections Bundle 1 (Problems with the “perceives” relation) God feels pain Extended ideas can’t fit in an unextended mind Bundle 2 (Problems with unperceived existence) Ordinary people think objects continue to exist unperceived My ideas are different from anyone else’s Bundle 3 (Problems with notional self-knowledge) We are in no position to claim notional self-knowledge A Problem Case: Pain To feel pain is to be pained. Pain is therefore as much a way in which a mind exists as it is an “idea” perceived by the mind. This draws Berkeley’s distinction between minds and ideas into question. Some ideas (esp. pain and pleasure) are states of mind, that is, ways in which minds exist. (Think what a large role the identification of ideas with pleasure/pain plays in Berkeley’s argument.) A Further Problem Case Extension Berkeley insisted that to feel extension is not to be extended. So that extension is at most a quality of an idea and not a quality of a mind. But to feel pain is to be pained. Are there two different ways an idea might be perceived? Does God Feel Pain? When answering this question, Berkeley maintained that there are in fact two different ways of perceiving an idea: by “sensing” it by “understanding” it God is supposed to “understand” pain without “sensing” it. Do we all just “understand” extension without “sensing” it? Some Problems Our ideas of tangible extension are not separable from ideas of heat/cold or pressure. But these ideas are just forms of pleasure/pain. So Berkeley can’t take perceiving (sensing) pain to be a different thing from perceiving (understanding) extension It becomes unclear how sensible things can be perceived by God in our absence. (Because sensible things are just collections of ideas and the ideas that God understands are nothing like the ideas that we sense.) If perceiving an idea involves being a certain way, then it is clear that an idea cannot exist apart from being perceived. But if the mind is not affected by what it perceives, then it is not obvious why the idea should not be able to exist on its own. If God can understand pain without feeling pain, then there is a sense in which an idea (understanding) of pain can exist even though the object this idea represents (sensed pain) does not exist. So, in principle, having an idea is no guarantee of the existence of the object of the idea. Berkeley’s Distinction Between Sensing and Understanding an Idea We are just minds who do not have corporeal sense organs. So how do we distinguish “sensing” from “understanding”? Berkeley: ideas of sense are regularly preceded by other ideas of sense (alterations in the environment or the sense organs) But the difference between sensing pain and understanding pain is not just a difference in the ideas that precede the occurrence of the pain idea. It is rather a difference in whether you are affected by the pain or not Unperceived Existence What does it mean for an idea to be perceived by someone else when I do not perceive it? Answer 1: Ideas are public objects, existing outside of all minds. This is inconsistent with “esse est percipi” Answer 2: Ideas are private objects, existing only “in” (or “for”) the mind that perceives them (Given the opacity of the “perceives” relation, it is unclear what “in” means.) Then the real thing that is my collection of ideas of sense is different from the real thing that is your (or God’s) collection of ideas My collection of ideas does not continue to exist when I look away. A (Malebrancheian) Answer Suggested by Berkeley’s Argument for God’s Existence Ideas of real things exist in God’s mind, not in mine. When God reveals these ideas to me in accord with laws of nature … … this doesn’t mean that God creates copies (ectypes) of his (archetypal) ideas in my mind … it rather means that he lets me look at the ideas that exist in him Problems with this Answer God’s ideas aren’t at all like my own (see above) When I perceive one of God’s ideas, I must be altered in some way. The alteration in me that consists in my perceiving the idea must be distinct from the idea (which is in God) But then in principle I could be altered in this way even though the idea does not exist Another way of putting this: the idea, insofar as it is anything to me, must really be an alteration in me An Alternative Answer Identity is a fuzzy notion A real object is a collection of ideas commonly observed to go together and called by a single name. The collection does not just include ideas of different senses and ideas of imagination serving as images of ideas that are had earlier or later by the same sense It also includes ideas of the ideas of others, appropriately adjusted for their different perspectives An object can be said to exist unperceived by me as long as others have the appropriate ideas and use the same name, even if those ideas are not strictly identical. A Problem with this Answer Though the ideas of others need not be identical to mine, they cannot be of just any sort whatsoever, particularly as regards ideas of primary qualities. I envision other minds to occupy locations in space outside of me and to perceive 3-D objects in the common space between us from different perspectives. An application of perspective geometry to my ideas of the shape and position of the object leads me to deduce what ideas of primary qualities are appropriately experienced by others. Consequence: I can’t begin to formulate what ideas are “identical” without presupposing an external world containing public objects that determine what ideas are experienced by others. My practice therefore contradicts my theory. Notional Self-Knowledge Hume’s objection: (echoed by Hylas) Let me “reflect” as closely on myself as I want, I never discover anything but a constantly changing ideas Even when experiencing myself as willing, I only discover volitions, which are a kind of idea … … and which are at best regularly (though not invariably) correlated with effects Berkeley’s Answer A colour cannot perceive a sound or a sound a colour. In general, an idea cannot perceive another idea. So there must be something else besides ideas that perceives them. This thing is what we call a mind. Hume’s Reply (not echoed by Hylas) Each simple idea is complete unto itself, lacking nothing for its existence (a colour point can exist apart from a sound or apart from any other idea and so lacks nothing that I can conceive in order to be able to exist) If you say an idea cannot exist apart from a mind, I ought to be able to conceive what you mean by “mind” and feel compelled to add that thing into the idea of a colour point as a condition of forming the idea. But there is nothing that is meant by the terms “self” or “mind,” so nothing that can be added. (A notion of myself would have to be a notion of something that is with me every moment of my existence. But I have no such notion.)