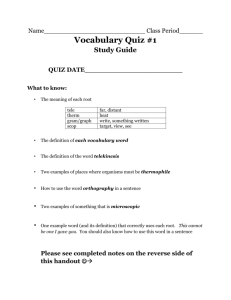

1. What is an orthography?

advertisement

Designing an Alphabet for an Unwritten Language

Roger Stone

Neri Zamora

SIL International

SIL Bagabag

3711 Nueva Vizcaya

Roger_Stone@sil.org

TAP

P.O. Box 1183 (MAIN)

1151 Quezon City

Neri_Zamora@sil.org

ABSTRACT

In this paper, we describe the process of developing an alphabet

or orthography for an unwritten language.

Categories and Subject Descriptors

not understand the ramifications of each choice they make.

Educators will often be the first users and implementors of an

orthography so their input in the process can be invaluable.

3. Processes of orthography development

[Orthography Development]

3.1 Linguistic analysis

General Terms

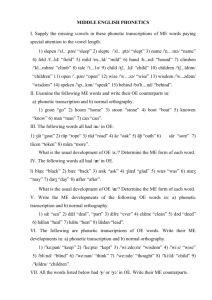

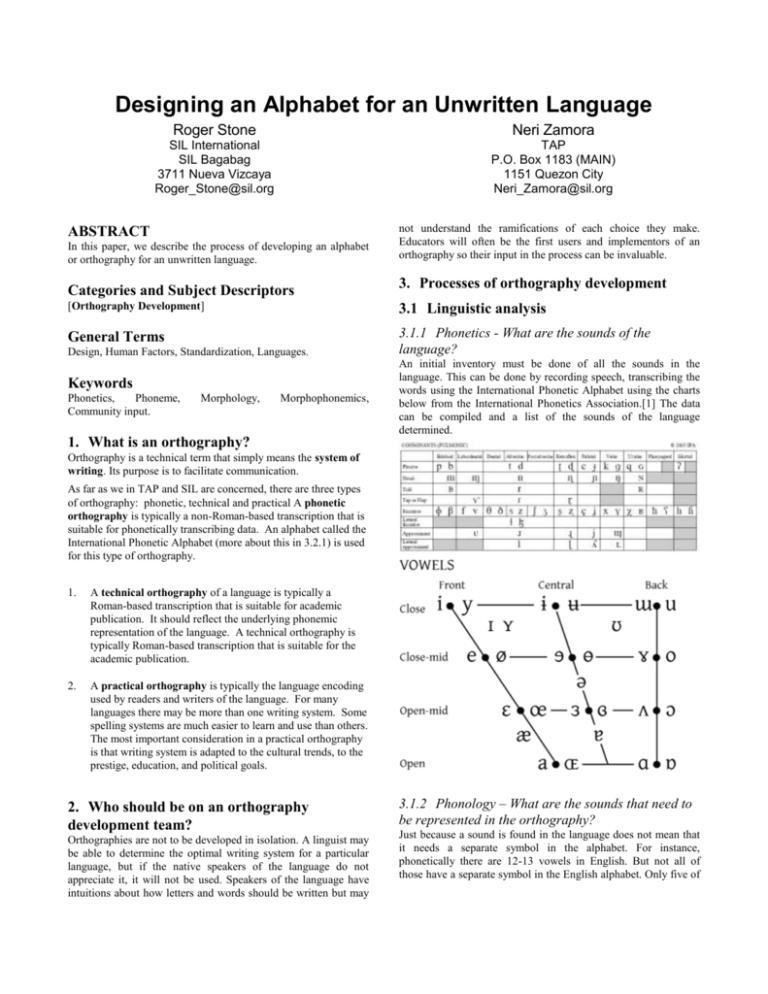

3.1.1 Phonetics - What are the sounds of the

language?

Design, Human Factors, Standardization, Languages.

Keywords

Phonetics,

Phoneme,

Community input.

Morphology,

Morphophonemics,

An initial inventory must be done of all the sounds in the

language. This can be done by recording speech, transcribing the

words using the International Phonetic Alphabet using the charts

below from the International Phonetics Association.[1] The data

can be compiled and a list of the sounds of the language

determined.

1. What is an orthography?

Orthography is a technical term that simply means the system of

writing. Its purpose is to facilitate communication.

As far as we in TAP and SIL are concerned, there are three types

of orthography: phonetic, technical and practical A phonetic

orthography is typically a non-Roman-based transcription that is

suitable for phonetically transcribing data. An alphabet called the

International Phonetic Alphabet (more about this in 3.2.1) is used

for this type of orthography.

1.

A technical orthography of a language is typically a

Roman-based transcription that is suitable for academic

publication. It should reflect the underlying phonemic

representation of the language. A technical orthography is

typically Roman-based transcription that is suitable for the

academic publication.

2.

A practical orthography is typically the language encoding

used by readers and writers of the language. For many

languages there may be more than one writing system. Some

spelling systems are much easier to learn and use than others.

The most important consideration in a practical orthography

is that writing system is adapted to the cultural trends, to the

prestige, education, and political goals.

2. Who should be on an orthography

development team?

Orthographies are not to be developed in isolation. A linguist may

be able to determine the optimal writing system for a particular

language, but if the native speakers of the language do not

appreciate it, it will not be used. Speakers of the language have

intuitions about how letters and words should be written but may

3.1.2 Phonology – What are the sounds that need to

be represented in the orthography?

Just because a sound is found in the language does not mean that

it needs a separate symbol in the alphabet. For instance,

phonetically there are 12-13 vowels in English. But not all of

those have a separate symbol in the English alphabet. Only five of

those sounds are represented in the alphabet because there are

only five “phonemes”.

The e in the English word roses is a good example. The phonetic

sound is ɨ but the symbol e is used. The sound that actually comes

out of people’s mouths is different than the prototypical e sound.

Why does this happen? Sounds are influenced by the sounds

around them. The presence of two s or z sounds (both symbolized

by “s”) causes the e sound to become phonetic ɨ. This is

predictable in light of the s or z sound being made by when the

tongue is placed in the middle of the mouth. The e sound also is

made in the front of the mouth whereas the ɨ sound is made in the

middle of the mouth. So, the e sound assimilates to the place of

articulation of the consonants around it.

In Ayta Abellen there are four vowel phonemes although if one

listens to speakers of the language and carefully transcribes the

uses of the vowel o, one will hear that sometimes the speakers are

actually saying u. To date the orthography has only been using

one symbol o for these two sounds and we have yet to discover a

word where not writing two symbols has affected reading ability.

So, if sounds are being influenced by the sounds around them,

how do we know when to use two symbols or just one? In

phonology there is a term called “minimal pair”, where two words

have all the same sounds except one. When this happens we can

say that the difference between those two sounds is significant and

most likely the distinction will need to be represented in the

orthography. An example in Tagalog is kulay and gulay. Even

though k and g are phonetically similar (both made by placing the

tongue at the back of the mouth) there have to be separate k and g

symbols in the Tagalog orthography so that the differences in

meaning can be determined by the reader.

consistently. In the case of the example above, the third sample is

the most common way of writing this in Ilokano with the pronoun

attaching to the verb and the two particles being written as

separate words.

3.1.4 Morphophonemics – What to do when affixes

collide?

Morphophonemics is “the study of phonemic variations in

morphemes”. When a prefix is added onto a root there may be

changes in the sounds made either at the end of the prefix or the

beginning of the root. A simple example is darating in Tagalog.

We know that the root is dating and the prefix is da-. The sound

that is actually pronounced, though, is r and so the Tagalog

orthography calls for writing this phonetically rather than

phonemically. Phonemically this would be dadating.

Language communities might not always want to choose the

phonetic spelling as they may want to retain the original phoneme.

For example the Ayta MagIndi have a prefix in-. When it attaches

to a root that begins with p or b the natural tendency is to say im-.

When occuring before roots beginning with t or d the natural

tendency is to say in- and when before k or g the tendency is ing-.

At present the Ayta MagIndi writers are trying to decide whether

it is best to write all of these cases as in- or to alternate between

im-, in-, and ing- depending on the following letter.

3.2 Community Input

“Orthography development is a participatory process. It should

be designed, implemented, and managed by the language

community. During the process, participants must make many

decisions related to factors that affect orthography development.

Stress can also be phonemic but is often not written as in the case

of ta’yo ‘to stand’ and ‘tayo ‘we’. In cases like this the context

may be used by the reader to determine which form is being

referenced.

As participants become more and more aware of the structures of

the language, they will need to make orthography revisions.

During the process of testing and revising, a developing

orthography is classified according to the type of revisions it has

undergone.”[2]

3.1.3 Morphology – Where do the words and affixes

begin and end?

There are often three stages in the process. Stage one is a trial or

“initial” orthography. Stage two is an approved or “working”

orthography. Stage three is an established or

“standard”

orthography.

Morphology is the identification, analysis and description of the

structure of words. This includes the identification of the

boundaries between prefixes, suffixes, and infixes in relation to

the root. It also includes the identification of the boundaries of

words.

4. Questions to consider

“Is it easy to teach?

For unwritten languages it is important that there is adequate

analysis of where words begin and end. For instance, many

northern Philippine languages like Ilokano have pronouns and

particles that always follow the verb and when people speak it can

sound like those words are attached. For instance, the phrase “I

also would like to stand” could be written any of several ways.

Is it easy to read?

Is it easy to write?

Can it be typed?

Will words be too long?

Will bridging to Tagalog be difficult?

Tumakder ak koma metten.

Do people like it”[3]

Tumakderakkomametten.

Tumakderak koma metten.

Tumakderak komametten.

It is important that the word divisions and their parts of speech be

understood so that if there is a desire to attach some of the parts of

the speech to the verb, a principled writing system can be

specified where words and sentences can be constructed

5. Potential problem areas for Philippine

languages

Use of “o and u”

Symbolization of the offglides (e.g. sya, bwaya)

Symbolizing the glottal

Representation of the juncture of “n” and “g” when they do

not form “ng”

Readability of reduplication (use of hyphen)

Hyphenation

Vowels that are dropped from words during affixation (also

fast speech although it is normally written in the full form)

Contractions

Consonant gemination

Pronoun attachment

Compound words

6. Orthography development samples

6.1 Bolinao

Four areas that we considered when we formed the Bolinao

orthography:

The linguistic evidence (phonemics).

Graphic considerations (writing

instruments available).

Pedagogy (its teachability).

The social acceptance (cultural

considerations).

systems

and

and

political

6.1.1 The Linguistic Evidence (phonemics)

The ideal for a writing system based on sounds is that one and

only one symbol would represent each “emic” sound. (Emic

sounds are the sounds that would change the meaning of a word).

In Bolinao orthography, the letters being used for the nonborrowed words except proper names are: a, b, d, e, g, i, k, l, m, n,

ng, o, p, r, s, t, w, y, and ‘. In borrowed words or loan words all of

the letters of the Romanized alphabet are used following first of

all the spelling in Filipino and, if that is not applicable, then the

foreign spelling.

Letters for which the symbols are consistently used in Bolinao,

Tagalog and Ilocano (the lingua franca) languages are:

a, b, d, g, l, m, n, ng, p, r, s, t

6.1.2 Graphic considerations (Writing systems and

instruments available)

If possible the symbols should be readily reproducible by local

means.

1.

2.

3.

Ideally, the symbols chosen should be available on the

standard typewriter and computer keyboards, printing

presses, or typesetters.

The symbol should be legible even with diacritics.

The symbol should be easily written in cursive script.

Symbols that could be embarrassing to a people group because of

their strangeness should not be used. We did not use, for

instance, η for ng? or for a? or ʃ for sya? or j for y?

6.1.3 Pedagogy (its teachability)

One test of a good orthography is that the speaker of the language

be able to learn to read and write it. Or to put it another way, the

written language should be readily teachable. This makes

consistency a very important factor in developing an orthography.

It also means we need to keep relearning to a minimum. Thus

what is already being taught by local school and for the

national language is a heavy factor to consider. Having learned

to read the national language or the trade language of the area, a

reader should be able to read in his native language with as little

difficulty as possible as the transference of the value of the

symbols. But, Smalley (1963:23) has summarized an alternative

viewpoint as follows: It is not what is easiest to learn, but what

people want to learn and use which ultimately determines

orthographies.” We need to be open and very flexible in our

attitudes as we seek to formulate orthographies.

Part I of the orthography testing done in 1980 was a spelling test

consisting of 65 words given orally in order to give opportunity

for individuals to write words as they thought they should be

written.

Part II was a multiple choice test that gave opportunity to choose

from various options. The results of Part I and Part II were

consistent with each other and confirmed the present orthographic

choices. Amongst the older people there was some use of C and

QU instead of K but even there some consistently used K. The

younger people used the K. The younger people tended to use the

hyphen for the glottal sound in the position following a consonant

as in Tagalog but otherwise consistently used a symbol similar to

the apostrophe preceding a consonant. Final glottals were

generally marked. The symbols used in the pre-consonant and

final positions were first the apostrophe ('), second the grave

accent (`) third the circumflex (^). The use of offglides, Y and W,

depended on if the word used was cognate in Tagalog or Ilocano.

The corresponding shape was used. All permutations were used.

Generally the O-U rule of the last syllable using O, and U being

used elsewhere was followed except by the older people who

retained the shape of the root when affixing or reduplicating. The

separation of particles following the verb and pronouns was based

on the formation of the stress groups which normally meant the

pronouns were separated from the verb and grouped into separate

words containing more than one morpheme. These pronoun

“words” may or may not contain some of the particles.

Part III of the test was to demonstrate readability. Part A

involved reading individual words out of context and Part B

involved reading a story given by a Bolinao speaker. The reading

test gave results consistent with the demonstrated reading ability

of the person in other areas and so confirmed the orthographic

choices.

6.1.4 The social acceptance (cultural and political

considerations)

What the people will use is the ultimate force. Of course we can

anticipate this to some extent and also train people in the

“official” way but after that, it will come back to what is being

accepted and used.

A primary factor here is the major language. In your case,

Tagalog or Filipino has the primary influence since that is what is

taught in schools, heard on TV and offers advancement within the

country. This will influence the choice of symbols, word breaks,

glides and other choices.

Also, history affects the cultural pressure and so we have

conflicts in Bolinao between Spanish spellings and national

language spelling. The Spanish Romanized the ancient Baybayin

form of writing. They, however, had no “K” in their alphabet and

so used ”C” and “QU”. They also had difficulty in representing

the “NG” sound and used several ways to try to represent this as

one sound. The “W” sound was also absent in their Romanization

and so they used diphthongs instead (au, iu, ou, oe, ua, ui, and

uo). Rizal tried to harmonize these points in Tagalog when he

simplified the Spanish “C” “CQ” and “QU” to “K” and the

problem of diphtongs by the use of “W” and “Y”.

The preferences of people is also considered. You may have

varying opinions on the marking of the glottal. In Bolinao, it is

generally the older people that want to retain “C” and “QU”.

Pressures that may be placed by the government (approval of

KWF) on languages may also be a factor.

6.2 Ayta languages

The orthographies of the Ayta languages are not as developed. An

orthography was developed for the Ayta MagAntsi language in

conjunction with the publication of the Ayta Mag-antsi-English

dictionary and the Ayta Mag-antsi New Testament but the other

Ayta orthographies are still in process.

The other Ayta languages have initial orthographies that are being

used for test publications. The process being utilized here is what

I call background analysis. As mother tongue speakers draft

translated and original materials the linguist is watching for

patterns and informing the writers about the implications of the

emerging patterns. For example, if a writing pattern is noted that

seems to capture better what is really happening in the language, I

present the pattern to the writers and ask if they would all like to

make that change. If yes, then the writers adjust their future drafts

and I use regularized expression search and replace capabilities in

software to change existing documents. I also inform the writers

of patterns that are not in conformity with the overall orthography.

In this way the writing system is improved over time as the

different choices are discussed in context. It’s kind of like

ongoing analysis is being done in the background.

7. Suggested Practical Procedure

Assess the language and cultural situation

Help community produce some sample materials

Test the materials with readers

Revise orthography as needed

Prepare more sample materials

Present findings to community and seek consensus

through a “Language Congress”

Revise orthography in response to community input

Submit to LGU and/or Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino

8. Computational Tools Available

8.1 Speech Analyzer for Phonetic analysis

Speech Analyzer is for recording speech and analyzing the

resulting wave files. The tool can be useful for determining

syllable length, stress, and even the correct phonetic symbol for

individual sounds. It is downloadable at:

http://www.sil.org/computing/sa/sa_download.htm

8.2 Phonology Assistant for analyzing the

sound system

Phonology Assistant takes phonetic data and helps the analyst

find the patterns in the sound system of the language. It is

downloadable at:

http://www.sil.org/computing/pa/

8.3 FLEx/WeSay for dictionary storage

FLEx is a powerful tool for dictionary development and language

analysis. The tool is designed specifically for these tasks and can

handle virtually any writing system (definitely all in the

Philippines). There is a learning curve to using it but it is free and

very powerful for lexicography and analysis. It is downloadable

at:

http://www.sil.org/computing/fieldworks/flex/

A much less powerful but much easier to use solution for enabling

native speakers of languages to document their words (and the

meanings) is called WeSay. It can run on any Windows or Linux

computer and is also freely downloadable. Teaching someone how

to use it who is not familiar with computers is very simple. It is

downloadable at:

http://www.wesay.org/wiki/Downloads

9. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our thanks to SIL and TAP.

10. REFERENCES

[1] SIL International Literacy Department. 1996. “Develop an

Orthography”. SIL LinguaLinks Library.

[2] http://www.langsci.ucl.ac.uk/ipa/ipachart.html

[3] Easton, Catherine and Diane Wroge. 2002. Manual for

Alphabet Design through Community Interaction for Papua

New Guinea Elementary Teacher Trainers. SIL Papua New

Guinea.