M. Bakhtin - Carleton University

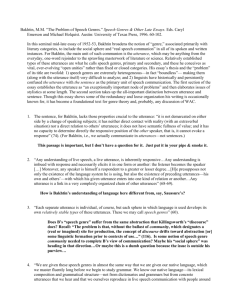

advertisement

Natasha Artemeva Carleton University, SLALS Course 29.573 – Winter 2002 Bakhtin Biography: Born in Orel in 1895 Family moves to Vilnius, Lithuania Family moves to Odessa Starts university there in 1913 Moves to Petersburg, continues at Petersburg University; “Bakhtin circle” comes into existence Moves to Nevel (Belorus) in 1918 (teaches at school) Moves to Vitebsk (cultural boom) Moves to Leningrad (former Petersburg) in 1924, works at the Leningrad Historical Institute Arrested in 1929 (“Problems of Dostoevsky’s poetics” and “Marxism and the Philosophy of language” (Volshinov) published) Exiled to Kazakhstan (works as a bookkeeper) Moves to Saransk in 1936, starts teaching at Mordovian Pedagogical Institute Moves to Kimry in 1937 Moves to Moscow region in 1940 (second world war) Returns to Saransk after the war, continues to teach there Retires in 1969 and moves to Moscow Dies in Moscow in 1975 The work of Russian literary theorist, M. M. Bakhtin, especially his essay "The Problem of Speech Genres" (1986), is fundamental for the social constructionist view of genre. His ideas have enhanced our understanding of the social embeddedness of genres (both oral and written) within communities of language users and, therefore, are central for understanding social aspects of writing process. Bakhtin (1986) defines speech genres as "relatively stable types" (p. 60) of utterances, thus providing two useful concepts for understanding the nature of genre: the responsive utterance as the analyzable unit of speech (rather than the word or sentence) and the addressive nature of speech. Describing an individual's speech (both oral and written) as always situated within the speech of others, he stresses the importance of recognizing the plurality of speakers in order to examine language use as communication (Hunt, 1994). For Bakhtin, the “responsive utterance” is the fundamental unit of analysis of human communication because it "occupies a particular definite position in a given sphere of communication" (1986, p. 91) (emphasis in the original). He sees an utterance as a link in a chain of discourse and points to its dual nature: any utterance simultaneously responds to past utterances while also anticipating future utterances. In Bakhtin's view, words and sentences acquire meaning through the utterance, and speakers choose the generic form of utterance which best meets their "speech plan or speech will" (p. 77). The dialogical principle of language presupposes the importance of addressivity. Without an addressee to whom an utterance is directed, it loses its dialogic context and turns into a separate Natasha Artemeva Carleton University, SLALS Course 29.573 – Winter 2002 statement "belonging to nobody." Bakhtinian notions of the addressivity of speech indicate the degree to which individual texts act as links between previous texts and the inevitable response of others. The dialogic nature of speech, the necessity for a change of speaking subject and a respondent, the process of utterance exchange, all this reveals the communicative sense of oral language. According to Flower (1994), "Much the same thing is said to happen in writing" (p. 60). In his theory of genre, Bakhtin introduced the dimension of time-space, which he calls chronotope (1981a). Schryer clarifies this notion by explaining that “genres express space/time relations that reflect current social beliefs regarding the placement and action of human individual in space and time . . .. In each chronotope, differing sets of values are attached to human agency. Agents in some chronotopes have more access to meaningful action or power than in other chronotopes ” (2001, p. 450). Genres involve both form and content which are inseparable. The form of discourse in the field changes along with the changing intellectual content. As Freedman and Medway (1994a) state, "[P]articularly significant for North American genre studies has been Bakhtin's insistence that . . . generic forms 'are much more flexible, plastic and free' (1986, p. 79) than grammatical or other linguistic patterns" (p. 6). Far from being rigid templates, genres can be modified according to rhetorical circumstances (Berkenkotter & Huckin, 1995). In Miller's (1984) words, genres evolve, develop, and decay. The better one's command of genres, the more flexibility and freedom one can apply in using genres. Thus even acting recurrently in a recurrent situation, one can express one's individuality. Therefore, "creativity is possible and visible everywhere, although Bakhtin insists that 'genres must be fully mastered to be used creatively'" (Freedman & Medway, 1994a, p. 7). Modern North American understanding of genre is reflected in Schryer's view (1994a) that genres represent “stabilized-for-now” or “stabilized-enough” sites of social and ideological action. Schryer (2000) redefines genres as “constellations of regulated, improvisational strategies triggered by interaction between individual socialization . . . and an organization” (p. 45). She further unpacks the definition by adding that “as constellations of flexible yet constrained resources, genres function as . . . sets of strategies . . . that agents use to mutually negotiate or improvise their way through time and space” (2000, p. 450). This perspective on genres allows us to view the process of student acquisition of domain-specific communication strategies as the process of student acquisition of domain-specific genres. As this brief overview of Bakhtinian dialogic approach to genre studies has shown, genres are fully mastered only by “insiders” of a particular Natasha Artemeva Carleton University, SLALS Course 29.573 – Winter 2002 community and are best understood in action. **************** Understanding of language through the ownership of meaning: Personalist view (“I owe meaning”) – I am a unique being and the sense of my language (meaning is in the unique individual). Meaning – inner space Deconstructionist view (“No one owns meaning”). Meaning – elsewhere Dialogism – “We own meaning” or “If we do not own it, we may at least rent meaning” “Meaning is made as a product” (Holquist, p. 391) Meaning – in-between (+ Louise Rosenblatt – transactional theory – meaning is in transaction) For a more detailed discussion, see Michael Holquist (1997). The politics of representation. In Cole, M., Engestrom, Y., Vasquez, O. (Eds.). Mind, Culture, and Activity. pp. 389-408. Cambrige: Cambridge University Press