THE MINERAL TRADE AND BANJA SLAVES IN EASTERN CONGO:

advertisement

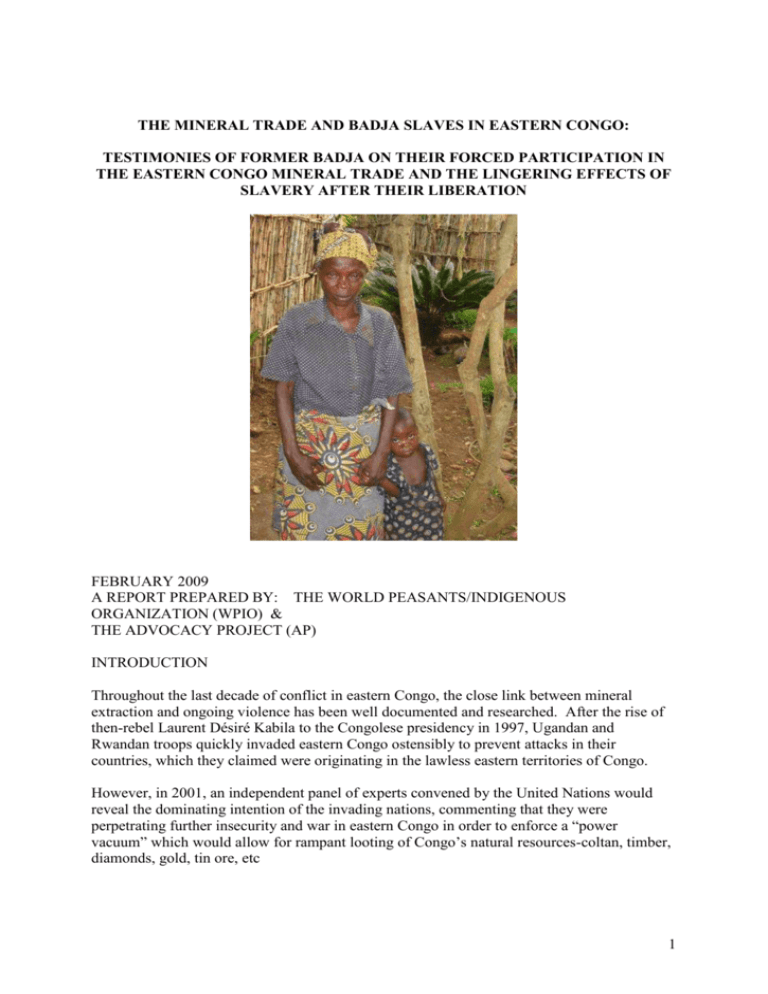

THE MINERAL TRADE AND BADJA SLAVES IN EASTERN CONGO: TESTIMONIES OF FORMER BADJA ON THEIR FORCED PARTICIPATION IN THE EASTERN CONGO MINERAL TRADE AND THE LINGERING EFFECTS OF SLAVERY AFTER THEIR LIBERATION FEBRUARY 2009 A REPORT PREPARED BY: THE WORLD PEASANTS/INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATION (WPIO) & THE ADVOCACY PROJECT (AP) INTRODUCTION Throughout the last decade of conflict in eastern Congo, the close link between mineral extraction and ongoing violence has been well documented and researched. After the rise of then-rebel Laurent Désiré Kabila to the Congolese presidency in 1997, Ugandan and Rwandan troops quickly invaded eastern Congo ostensibly to prevent attacks in their countries, which they claimed were originating in the lawless eastern territories of Congo. However, in 2001, an independent panel of experts convened by the United Nations would reveal the dominating intention of the invading nations, commenting that they were perpetrating further insecurity and war in eastern Congo in order to enforce a “power vacuum” which would allow for rampant looting of Congo’s natural resources-coltan, timber, diamonds, gold, tin ore, etc 1 A study done in 2002 by the POLE Institute on coltan exploitation in eastern Congo added to the UN assertion, noting the emergence in mineral trading of a, “…mafia economy organized around rebel armies and their allies, and the armed Mai-Mai groups.” Although the war would be technically ended in 2003 with the signing of the Global and Inclusive Accord (“Pretoria Agreement”) which also lead to the withdrawal of all remaining foreign troops, the wealth of natural resources which should have been a catalyst for Congo’s development continued to burden efforts at solidifying real peace and raising standards of living for Congolese. As late as 2006, Refugees International would comment that natural resources in Congo were still “at the root” of Congolese conflict and the ongoing humanitarian crises. As the humanitarian crisis in Congo has persisted, so does the presence of non-state armed groups and a state of general impunity, which of course has direct implications on natural resource exploitation and the Congolese who form key elements of the supply chain. In November of 2008, a New York Times journalist was given access to one mining region currently under the control of Mai-Mai militia in eastern Congo who export as much as $80 million worth of tin ore per year, mostly through the exploitation of an informal and desperately poor local labor force working under the direct threat of violence. The article summarized the present situation of the mineral trade in eastern Congo, “The wealth is unearthed by the poor, controlled by the strong, then sold to a world largely oblivious of its origins.” INDIGENOUS PEOPLE, OR PYGMIES, AND THEIR ROLE IN EASTERN CONGO MINERAL EXTRACTION This report is meant to give voice to the “bottom rung” of the trade in natural resources in eastern Congo, the impoverished Congolese providing the source of labor in mines and forests necessary to export vast amounts of natural resources but receiving virtually nothing for their efforts but broken families and lives dominated by fear and violence. In eastern Congo, a well-entrenched system of slave labor exists, which involves the forced labor of enslaved Pygmies and indigenous people, called badja, who are often born into slavery or captured by various militias and land owners in the region. Local leaders in villages will often coerce vulnerable indigenous people into badja slavery by promising pay which never arrives, or forcibly recruit badja by arming themselves and local militias and then simply threatening violence should the Pygmies refuse to partake in slave labor. The stories compiled in this report will demonstrate that these threats are far from empty. Once enslaved, the badja act as forced labor unit, often engaging in the mining of precious minerals, commercial farming, portage, and construction. Female badja are regularly given as payment soldiers and miners, and these “bush wives” are forced into sex slavery in addition to the aforementioned tasks. The men and women the World Peasants/Indigenous Organization (WPIO) and The Advocacy Project (AP) field workers interviewed were all badja in various mining areas across eastern Congo, and freed due to WPIO negotiations with village slave-holders and militia, who were using the badja as unpaid labor in the artisanal, or informal, mining operations which dot North Kivu, South Kivu, and Maniema provinces in eastern Congo. After negotiating their freedom, the WPIO provides 2 freed badja with plots of land for cultivation to counteract the reality that, as slaves, baja seldom have any familial land of their own at all. Also, the WPIO works with freed slaves to inform them of their human rights in order to protect them from future re-enslavement, a persistent problem in the region. Further, freed slaves are given basic agricultural, income management training, and as hospital care is often required for those departing the mines, WPIO works with local hospitals to provide basic care to freed badja. The following testimonies were all given to WPIO and AP field workers in December 2008, and have been quoted and paraphrased from the stories told by the badja. The body of work directly concerning indigenous peoples and their relationship with mineral extraction in eastern Congo is sparse, especially in terms of the role badja slaves play as the source of many of the most sought after minerals exported from Congolese territory. Having read the stories contained herein, it is the responsibility of the international community, civil society, and all those interested in protecting human rights across the world to take a firm stand against modern-day slavery in all its forms, and refuse to accept products derived from systems resembling badja slavery. Mineral and natural resource wealth in eastern Congo has long only deepened conflict in the region, and ending exploitation of some of the most vulnerable populations, indigenous and Pygmy communities, will play a significant role in reversing this violent trend. -Ned Meerdink, The Advocacy Project, 2009 * Mama Butale M. Butale began our interview by commenting, “I have never seen any joy in my life. I was born owned by someone.” Raised in Kalonge, South Kivu, M. Butale was born to enslaved parents, and was thus enslaved herself. Eventually, Mai-Mai militia soldiers captured her and her husband in their village, bringing them deeper into the interior (towards Bunyakiri, North Kivu), whereupon her husband was sold to a local mining company. “The mining company was not located far from where I was kept, and one day my husband was brought to the tin ore mine where I was working.” In front of her husband, the Mai-Mai in charge of the mine repeatedly raped M. Butale. Seeing her husband “in tears”, the soldiers then, “…cut off my husband’s head after telling him that I was their wife now, and said to me, ‘Your dog is dead.’” The soldiers then disposed of the severed head, but left the body, telling M. Butale to prepare it for them to eat. Widowed, M. Butale was left to work for the soldiers occupying the mine, carrying 20 liter containers of water the camp 4 to 5 times daily, walking “…at least 25km (about 16 miles) each day.” In addition, M. Butale was taken as a sex slave, and, “…any soldier who wanted to would have sex with me.” In this manner, M. Butale lived and found herself mother to 5 children, 2 by her deceased husband and 3 by unknown soldiers. 3 Freed in 2007 by WPIO negotiations with local slave holders and militias, M. Butale was given land in Cirunga, South Kivu to cultivate on. With her small plot of land, M. Butale attempts to save enough money to pay schooling fees for 2 of her children. Her oldest three children are still enslaved, and are working in mines despite being all under the age of 10. Commenting on her freedom, M. Butale said, “Being free has shown me the difference between darkness and light. I would have eventually been killed by the soldiers in the mines, but now I am free to die a natural death, a death of God. I may still be suffering, but I am no longer condemned to a quick and meaningless death.” Since her freedom was negotiated in 2000, M. Nyamigangu has been cultivating on land provided to her by WPIO, mostly beans, soya, and bananas. However, she commented that despite her being free, her suffering has changed, “…from physical to psychological because my three sons have died while working in mines. I am now old and alone and lonely in my life.” M. Nyamigangu was enslaved in a mine in North Kivu, probably on a coltan deposit located in Nyamukubi. She worked in the mine from 1996 to 2000, and despite being found working in 1997 by WPIO field workers, discussions concerning her freedom took until 2000 to succeed. During her slavery, she was used as a sex slave, and offered to the workers meeting their daily mineral quota, many of whom were also badja slaves. Asked by interviewers what her message was to Mama Nyamigangu the Congolese government concerning the situation of modernday slavery in Congo’s mines, M. Nyamigangu commented that, “…they are very careless because they know very well we exist and are forced to work in mines, but they do nothing to free us, to help us be free men and women.” She concluded her interview by noting that, “I am happy to be free even if I am suffering the killings of my sons. Please continue to help other condemned to hard slave labor. Mwami Arhahimwa Byamuhanya Arhahimwa, age 49, was born to enslaved badja, and himself married a badja. Thus, he has never been the owner of any land, which has created a difficult life for him. Lacking land, his wife and 5 children are all uneducated. Formerly enslaved at a mine in Lulimba, South Kivu, Arhahimwa noted that, “…education is key for Pygmy liberation. We Pygmies do not know our rights or the law in Congo, so it is simple to enslave us.” He went on, “Because Pygmies are not land holders, education could be a way out of poverty.” While enslaved, Arhahimwa mined for coltan, and was a porter for different armed groups. He still suffers from his lack of familiar land, in that the land which has been allotted to him by the WPIO is enough only for a small profit. While the WPIO negotiated his freedom and his family’s freedom with local chiefs, he commented that this was only, 4 “…an important first step. For me to live well I am in need of more agricultural education and possibly more land so that he can send my children can be educated someday.” When asked about the reality of family-based slavery, Arhahimwa reasoned that the sure way to end this is by direct negotiations between murhambo and those representing enslaved Pygmies. He is currently living and cultivating with his family near Kamalende, South Kivu. Matirita was found in 2007 by WPIO field workers working in a coltan mine near Bunyakiri, North Kivu. She was forced, while working in the mine, to serve also as a sex slave for soldiers and miners in the area. After years of this torture, Matirita began refusing to have sex with miners, and for this refusal, “…the mine boss approached me, had his friends hold me down, and tried to remove my eye.” Due to the frequency of the rapes, Matirita now has 6 children, with no known father. When the WPIO met Matirita in 2007, she had fresh wounds and sores all over her body, in addition to a serious infection where her eye had been extracted. She commented, “…my children are still slaves in Bunyakiri, but I am not sure where. I need my children to be truly free.” She went further, “I still dream of my past, what I was forced to do. There are still so many enslaved. Matirita Nankafu I am lucky to have one eye still, as I probably would be completely blind had I stayed in the mines.” Recent developments concerning the whereabouts of her children are encouraging, but negotiations have not yet begun concerning their freedom due to rampant insecurity in the Bunyakiri area. She now lives in Lugendo, South Kivu and cultivates on land given to her through WPIO negotiations with local chiefs. Sidonia was a sex slave and miner in mineral-rich Walikale, North Kivu. Like all other interviewed badja, slavery has touched her life profoundly. Born to slave parents, who were killed while working in the Walikale forest during a period of peak insecurity, Sidonia herself would eventually be enslaved in the same region. She stated, “…the mines killed my parents, so I am an orphan.” She was captured near her home village and brought to Walikale by unknown soldiers (likely Mai-Mai, as they control numerous mines in the Walikale region), and immediately began enduring, “…daily rape by soldiers and local mine workers.” In this manner, she gave birth to 4 children with no knowledge of the father. As for her children, “…they are still in Walikale, probably working in a mine.” After refusing to submit to sex with a local mine boss, Sidonia was held down and beaten. Eventually, “…the mine boss smashed my leg with stones.” She was, therefore, permanently handicapped and has been unable to work well since. The WPIO found Sidonia Sidonia M. Manywa Sidonia’s damaged leg 5 soon after this torture, with oozing sores, upon which Sidonia was taken to a local hospital. She concluded, “Slavery would have killed me, and I fear that my children will be killed, becoming orphans like me, if something does not happen soon.” She now lives alone in Burhalange, South Kivu, and cultivates a small plot with great difficulty. Oderhwa was found in slavery in Walikale in 2006, where he was mining tantalite for a local mine boss probably selling the minerals out of a Goma-based enterprise. However, he commented, as most badja did, that, “…I do not know where the minerals [I mined] were eventually taken.” Between his birth into slavery and his liberation in 2006, Oderhwa was unpaid, but, “…sometimes supplied with food.” Since his freedom was negotiated with local mine officials in Walikale, he has been cultivating beans and bananas on a small plot, but he comments that, “…more access to agricultural information is needed as I do not have the know-how to increase my yields.” Commenting on the difference between freedom and slavery, Oderhwa said that when he was a slave he, “…looked bad. I still may look Mulume Oderhwa Munyi bad but now I can choose my own way. No one can come and beat my buttocks and torture me.” Despite generating a small income, he is still unable to send his 4 children to school. He commented that education is a key for sustainable freedom and for keeping liberated Pygmies free, but that, “…there is just not enough for me now on my small amount of land to provide school for my children.” Stefania Safani Stefania began her interview by giving her idea of what slavery means in commenting, “…you [the international audience] might not know what the word ‘slave’ really means, but for us badja, it means ‘evil’. To free slaves like me from this evil is important. We need to make all badja free women and men.” She told her story, telling interviewers that, “…I was enslaved in Lulimba [South Kivu] mining for stones. Before I was freed in 2003, my husband had already been killed, but I don’t know exactly why.” Her 3 children are scattered across eastern Congo in “unknown” mines, but Stefania thinks that one child, “…fled to Uvira [South Kivu] to escape the mine where I was working.” The thought of her children is a painful one, as they remind her constantly of here days, “…having sex in the mines as a slave.” This pain remains, despite WPIO efforts which removed Stefania “…from the teeth of a lion.” 6 Lote Mupiga Found in a mine near Kalehe, South Kivu, Lote has been sewing when possible to make a living since her liberation. She was a sex slave, and has three children due to the rapes. Her husband was killed near a neighboring mine, but Lote was unsure of the circumstances around his murder. She commented that sice her liberation she feels, “…just useless because I am unable to provide enough for my children to live or go to school.” Lote is 1 of 5 recently freed badja who are waiting for an upcoming WPIO program providing new sewing machines and fabric. Demonstrating the dedication local mining concerns have to keeping the stories of the badja working on their mines quiet, a WPIO field worker was viciously beaten by soldiers and local miners running the mine near Kalehe for pursuing Lote’s freedom. * The Advocacy Project (AP) is a not-for-profit nongovernmental human rights organization based in Washington, DC, with a field office in Kampala, Uganda. Our mission is to produce social change by helping advocates for marginalized communities become catalysts for social justice and claim their rights. The Advocacy Project 1326 14th Street NW Washington DC 20005 phone: +1 202-332-3900 fax: +1 202-332-4600 7