Using the ELISA Assay for Disease Detection

advertisement

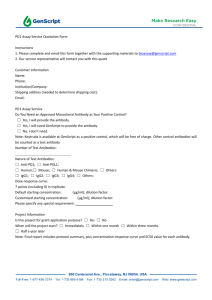

BIOTECH Project, University of Arizona ELISA Assay TEACHER GUIDE: Using the ELISA Assay for Disease Detection In this laboratory you will use the ELISA (Enzyme Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay) for detecting the presence of an antigen, such as a disease-related agent, from a sample of body fluid. You will be given a solution that represents your body fluid. You will exchange body fluid with three other individuals. The ELISA test will be used to detect a simulated disease agent in the mixed body fluids. Finally, you will analyze the class data set to determine identity of the original carrier(s). This assay is similar to that used for the AIDS test, in which an ELISA is used to detect individuals infected with the virus that causes AIDS (HIV). Materials: Each student should have the following items before starting the laboratory: * Microcentrifuge tube containing "body fluid" (BF) * Disposable transfer pipet Each group of three students should also have: * ELISA test plate The class should have * Positive and negative control solutions (+ and -) * Paper towels * Antibody solution (Ab) * Washing solution (in wash bottle) * Color reagent solution (TMB) Procedure: Exchanging Sharing Solutions 1. At the start, you'll have a transfer pipet and a tube containing a solution that represents your "body fluids." Be sure to choose students from all over the class, and not just in your immediate area. Wait for the instructor's signal before exchanging fluids. 2. Find one other student in your class and exchange your solution from your 'body fluid' tube with him or her. Use transfer pipet to swap half of your 'body fluid'. #1 sharing: Brian 3. At the instructor's signal find a different student to exchange your sharing solution with. #2 sharing: Susan 4. At the instructor's signal exchange your sharing solution with one more student. #3 sharing: Jennifer The three names written above are the people with whom one individual swapped body fluid. Be sure students swap only with three people and that everyone does their first swap simultaneously, then their second swap simultaneously, then their third. That way, things don't get confusing with one pair on their third swap while everyone else is on their second. 1 BIOTECH Project, University of Arizona ELISA Assay ELISA Test After all three contacts have been completed, you will do an ELISA test on your sharing tube fluid. 1. Form a group (usually four people) at your lab station. Your group will run an ELISA assay on your mixtures of body fluids from each student in your group using an ELISA plate. Students can partner up for the ELISA with whomever they'd like, not necessarily with their fluidswapping partners. For example, I swapped with Brian, Susan, and Jennifer, but my lab group for analysis is myself, Tom, Dick, and Harry. Students should record the names of their lab group on the table below for analysis (not their swapping partners, who should be recorded on the previous page so they don't forget). Make sure everyone in a group has their tables labeled the same way (with the same person in the first row, the same person in the 2nd row, etc.). Samples Loaded Results Myself __________________ Tom __________________ Dick __________________ Harry __________________ Positive (+) __________________ Negative (-) __________________ __________________ __________________ __________________ __________________ The last two rows are empty, which is fine, or the lab groups could be larger to use those last rows. 2. Using your transfer pipet, add three drops of your sharing tube fluid into each of three wells. Be sure to record which wells contain your fluid to avoid confusing your wells with another person's. 3. Each group will also do one positive and one negative control. Using the dropper bottle pipets for each control, add two drops of a positive test solution (+) into three wells and two drops of a negative test solution (-) into a different set of three wells. 2 BIOTECH Project, University of Arizona ELISA Assay 4. After everyone has added their solution, leave the plate on the lab table undisturbed for five minutes. While the samples are standing, I talk about the name of the test to get students thinking about what could be happening. The name is ELISA, which stands for Enzyme-Linked Immuno-Sorbent Assay. I ask the students to tell me what 'Immuno' means to them. Usually, they'll say something about the immune system. Then I ask what our immune systems use to fight disease, and at least one student says 'antibodies'. I'll ask if anyone knows how antibodies work (they stick to a foreign object like a bacterium or virus - called an antigen, so your body can recognize it as foreign and other cells come along and destroy anything that antibodies are sticking to). Scientists take advantage of the fact that we make antibodies that stick to almost every kind of diseasecausing agent. If we took those antibodies (for example, HIV antibodies) and stuck them on the bottom of a dish (like our ELISA plate) and put body fluid infected with HIV into the dish, what would happen? Students usually will say that the HIV will stick to the antibodies. I'll also ask: if we put body fluid infected with the flu virus into the dish, what would happen? Nothing would stick because the HIV antibody can only stick to HIV. By the way, 'Sorbent' means to stick, like the antibodies stick to the HIV. 5. Shake off the fluid into a nearby sink or designated container, making sure that the fluid has emptied from each well. Tap the plate upside down onto the paper towel to remove any excess liquid or bubbles. 6. Wash your group's plate 3 times and shake off. With this step, we wash off everything that isn't stuck (flu virus, for example). 7. Using the dropper for the antibody solution add two drops of the antibody solution (Ab) to each well. 8. Allow five minutes incubation time on the lab table and then shake off the fluid. We have to be able to tell where there is HIV stuck and where there isn't. What do we already know sticks to HIV? The HIV antibody! The Ab solution is made of antibody to HIV, what will happen when we add it? It will stick where there is HIV and not stick where there isn't. This brings us back to the name of the testWhat does 'Linked' mean? (Stuck together) What does 'Enzyme' mean? (Molecule that catalyzes a reaction, or does a specific job) The antibody we just added is 'linked' to an enzyme that changes the TMB solution (which we haven't used yet) from colorless to blue. So what happens if there is HIV in the body fluid? The enzyme-linked antibody should stick, and when we add the TMB it should turn blue. What about if there is no HIV in the body fluid? The enzymelinked antibody has nothing to stick to and so there will be no enzyme around to turn the TMB blue. Now it's time to wash off the unstuck antibody. 9. Wash your group's plate 3 times and shake off. 10. Using the dropper for the TMB solution add two drops of the color reagent solution (TMB) to each well. 11. Watch your plate for the next 5 minutes. What happens? Record your results in the table on page 2. 3 BIOTECH Project, University of Arizona ELISA Assay Watch to see which samples turn blue. This is easiest to view on a white background. Record on the data table on page 2 in the 'Results' column which samples turn blue and which stay colorless. Questions I ask in the meantime: What do you think the positive control is? Body fluid that definitely has HIV, so what should happen? It should turn blue. What do you think the negative control is? Body fluid that definitely doesn't have HIV, so what should happen? It should stay colorless. Finally, what about the word 'Assay'- it means test. So ELISA is a test to see if antibodies stick to an antigen (e.g. HIV) in your body fluid by linking the antibody to an enzyme that causes a visual change (like TMB turning blue). Laboratory Questions Each group will record the results of the tests. Be sure to record whether you are infected. You will also record your test results and list of partners on the blackboard. 1. Given the classroom data, who are the original infected carriers? Based on who has HIV, who doesn't, and who people swapped with, the students may be able to trace back to the original infected person. 2. Why were positive and negative controls needed? If the positive control doesn't turn blue, then maybe some people that have HIV also didn't turn blue (this is a false negative, see below). We have to include a positive control so that we know that everyone that has HIV definitely tests positive. If the negative control turns blue, then maybe some people who don't have HIV also turned blue (this is a false positive, see below). We have to include a negative control so that we know that everyone that doesn't have HIV definitely tests negative. 3. What was the purpose of washing the plates between addition of each reagent? You have to get rid of unstuck antibody. If you don't wash off the unstuck antibody, you may test positive even when you're negative. 4. Explain what is meant by a false positive test. Name one error that would result in a false positive test. See above. A false positive could result from many things, including not thoroughly washing off the unstuck antibody or having an antibody that sticks to other things besides HIV (this is called nonspecific), for example, the flu virus. Then, someone who has the flu might test positive for HIV. 5. Explain what is meant by a false negative test. Name one error that would result in a false negative test. See above. A false negative could result from many things, including too much washing or not 'sticky' enough antibodies, so that the antibody doesn't stick to the HIV and a person with HIV tests negative. 6. How can you protect yourself from transmitted diseases? 4