Section 1 - Bar Standards Board

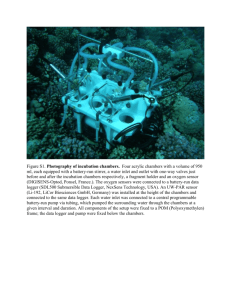

advertisement