Sarah Flannery - University of Kentucky

advertisement

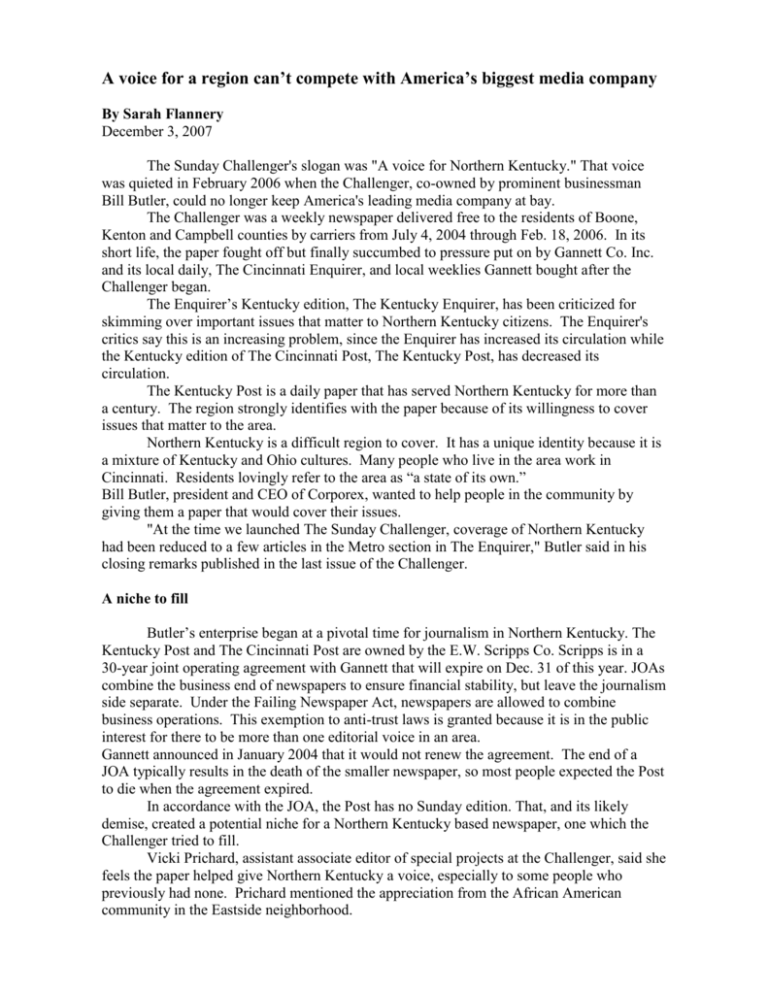

A voice for a region can’t compete with America’s biggest media company By Sarah Flannery December 3, 2007 The Sunday Challenger's slogan was "A voice for Northern Kentucky." That voice was quieted in February 2006 when the Challenger, co-owned by prominent businessman Bill Butler, could no longer keep America's leading media company at bay. The Challenger was a weekly newspaper delivered free to the residents of Boone, Kenton and Campbell counties by carriers from July 4, 2004 through Feb. 18, 2006. In its short life, the paper fought off but finally succumbed to pressure put on by Gannett Co. Inc. and its local daily, The Cincinnati Enquirer, and local weeklies Gannett bought after the Challenger began. The Enquirer’s Kentucky edition, The Kentucky Enquirer, has been criticized for skimming over important issues that matter to Northern Kentucky citizens. The Enquirer's critics say this is an increasing problem, since the Enquirer has increased its circulation while the Kentucky edition of The Cincinnati Post, The Kentucky Post, has decreased its circulation. The Kentucky Post is a daily paper that has served Northern Kentucky for more than a century. The region strongly identifies with the paper because of its willingness to cover issues that matter to the area. Northern Kentucky is a difficult region to cover. It has a unique identity because it is a mixture of Kentucky and Ohio cultures. Many people who live in the area work in Cincinnati. Residents lovingly refer to the area as “a state of its own.” Bill Butler, president and CEO of Corporex, wanted to help people in the community by giving them a paper that would cover their issues. "At the time we launched The Sunday Challenger, coverage of Northern Kentucky had been reduced to a few articles in the Metro section in The Enquirer," Butler said in his closing remarks published in the last issue of the Challenger. A niche to fill Butler’s enterprise began at a pivotal time for journalism in Northern Kentucky. The Kentucky Post and The Cincinnati Post are owned by the E.W. Scripps Co. Scripps is in a 30-year joint operating agreement with Gannett that will expire on Dec. 31 of this year. JOAs combine the business end of newspapers to ensure financial stability, but leave the journalism side separate. Under the Failing Newspaper Act, newspapers are allowed to combine business operations. This exemption to anti-trust laws is granted because it is in the public interest for there to be more than one editorial voice in an area. Gannett announced in January 2004 that it would not renew the agreement. The end of a JOA typically results in the death of the smaller newspaper, so most people expected the Post to die when the agreement expired. In accordance with the JOA, the Post has no Sunday edition. That, and its likely demise, created a potential niche for a Northern Kentucky based newspaper, one which the Challenger tried to fill. Vicki Prichard, assistant associate editor of special projects at the Challenger, said she feels the paper helped give Northern Kentucky a voice, especially to some people who previously had none. Prichard mentioned the appreciation from the African American community in the Eastside neighborhood. “I truly felt like we were giving a voice to some areas in NKY that had previously felt unheard,” Prichard said. “Just prior to the Challenger's demise one of their neighborhood associations recognized the paper at their annual awards ceremony for covering issues that mattered to them. They referred to the paper as a friend of their community.” The Challenger was different from its competition, the Sunday edition of The Kentucky Enquirer. Tom Mitsoff, the editor-in-chief of the Challenger throughout its operation, said the paper was meant to be more like a magazine than a newspaper. According to research done by Jessica Fisher for the 2005 Community Journalism class at the University of Kentucky, the paper focused mostly on feature stories with a highly local content. It had an entire section dedicated to local sports and hardly made mention of the surrounding Cincinnati area. The Challenger also had little national coverage besides issues that directly affected the local community. Since there was no paid circulation, the paper’s only source of revenue was advertising. The Challenger had many advertisers who were based in the community, but the paper could not persuade any of the larger companies to buy ads. Mitsoff said the larger companies were unable to see the potential market that the Challenger had. "We were successful with local advertisers, but couldn't reach the larger companies with offices out of town," Mitsoff said. "They couldn't feel the buzz the Challenger was causing." The distribution method the Challenger used was also unlike the competition. It was delivered, free, to about 77,000 homes. It was also available in restaurants, curbside boxes, offices and other sites on Sunday. This achieved total market penetration, meaning that it was able to reach all residents in Northern Kentucky. This is very valuable to advertisers who want as many people to see their ads as possible. The Enquirer, having a paid circulation, could not offer that. However, when Gannett bought a group of Northern Kentucky weeklies in March 2005, that was the beginning of the end for the Challenger, said Publisher Donald Then. “Once they joined forces it was tough,” Then said. That was one of the main reasons that the Challenger died, he said. With Gannett’s monopoly, it was able to offer advertisers combined rates. This means an advertiser could place ads in several newspapers for one price, rather than paying each paper an individual price. Then shared ownership in the paper. He was hired at Corporex, an investment and service firm, to do market research for Five Seasons Country Club. Starting a newspaper Getting the Challenger started took eight months of study and preparation. Then said the research included talking to more than 1,000 consumers and 500 businesses. The paper kept its plans under wraps until about three months before the first issue was published in July 2004. Then said the paper did not want the smaller weeklies to know what was going on. “We didn’t want the weekly papers to get wind and lock all their advertisers down,” Then said. The secretiveness was also partially due to Gannett's aggressive business philosophy. Richard McCord‘s book, The Chain Gang, documented that Gannett’s policy is to establish a monopoly status in its markets. Mitsoff was well aware of Gannett's reputation. "Gannett liked to X-out its competition," Mitsoff said. Gannett has ventures in newspapers, broadcasting and online advertising including sites like CareerBuilder.com. It is a very successful media company and owns 85 daily and 1,000 non-daily newspapers with a combined daily paid circulation of 7.2 million. For almost three months prior to its first print edition, the Challenger was produced online. After the Challenger began printing, it continued to put its articles on line, but put more focus on the print version. Mitsoff was one of the first employees hired. He had experience with small weekly papers in Ohio and Minnesota. Mitsoff was living in Minnesota and looking for work when he saw the ad in Editor and Publisher magazine looking for someone willing to be editor at a new Midwestern paper. Mitsoff had experience with starting a newspaper. In 1998 he started a twice-weekly newspaper, Beavercreek Current, with his sister in their hometown of Beavercreek, Ohio. Beavercreek has a population of about 38,000 and is located outside Dayton, about 50 miles north of Cincinnati. "We had a lot of competition, and [the paper] lasted four years until one of our competitors offered to buy us out, which we agreed to do," Mitsoff said. He knew the risks and struggles of starting a newspaper first hand, but thought there were good opportunities and decided to go to work for the Challenger. "You know you can't count on a long-term career," Mitsoff said. "[It] was a great chance to see what I can do in a metro market." Mike Jennings, the associate editor for projects at the Challenger, said he was also aware of Gannett's strong reputation for eliminating competition before he took on his position. He decided to take a chance and joined the Challenger staff. "I realized going in that it might be a short ride," Jennings said. Prior to working at the Challenger, Jennings was the communications director of the Kentucky Cabinet for Families and Children, and was a reporter for The Courier-Journal. He is a native of North Carolina. Beginning of the end In March 2005, 10 months after the Challenger opened its doors, Gannett bought smaller publications in the surrounding area. This is not uncommon for Gannett, but the presence of the Challenger may have put more urgency in Gannett’s plan. Gannett bought HomeTown Communications Network Inc., which owned the Community Press and Community Recorder in Cincinnati. HomeTown produced products in Ohio, Kentucky and Michigan, including newspapers, telephone directories, shoppers and niche publications. With the purchase of HomeTown, Gannett acquired the 26 individually edited community newspapers that were under the Community Press and Community Recorder. These publications reached 411,000 readers weekly in the Cincinnati metropolitan area and contributed to Gannett’s total market penetration in the area. Mitsoff said that when Gannett bought The Community Press and The Community Recorder, he knew the Challenger’s situation was getting "very bad." Mitsoff knew that if things did not change, the Challenger would be “X-ed out,” as Mitsoff put it. Then said he knew that Gannett was aggressive but he did not expect the company would buy the weeklies. He said a combined front was difficult for the Challenger to compete with. “The biggest issue was advertising,” Then said. He said that he thinks the paper would have had a better chance at competing with the weeklies if they were independent. “If the weeklies had stayed independent we were going after their dollar,” Then said. Jennings and Mitsoff agreed that the closing of the newspaper came down to a shortage of advertising. Jennings noted that as the Challenger's days were numbered when he saw Then putting more pressure on the advertising department. Quality doesn’t bring success Though the advertising department fell short, the news side was very successful. Mitsoff said he was very proud of the paper. According to a survey done by Media Audit, which used scientific surveys to determine what percentage of the marketplace was using what kinds of media, reported that over the course of one year, readership of the Challenger had tripled. Mitsoff, who hired the staff, said he was able to offer good salaries. This allowed him to hire many experienced journalists, who showed their stuff in the 2006 Excellence in Kentucky Newspapers awards. The Sunday Challenger competed in the associates category, for free-circulation newspapers. It placed in 12 of the 27 categories, winning six. Some of the titles it took home included Best News Story, Best Sports News Coverage and Best Feature Story. After 18 months of publishing and providing service to Northern Kentucky, the Challenger was forced to close its doors. The last issue was published Feb. 19, 2006. While Jennings and Mitsoff indicated that everyone on the staff was aware it could happen at anytime, no one was expecting it when the doors did close. Then broke the news. Mitsoff said he could tell that something was going on by Then's mannerisms, but was unsure of what. "He was holding out hope until the very last minute," Jennings said. The Friday afternoon of the last issue, Then called everyone together for a meeting. Jennings said that everyone was disappointed that a good newspaper was going away. "He put the paper to bed," Jennings said. He also described how the human-resource person was in the office asking them to look over and sign their severance agreements before they left that day. One staff member that stuck out in Jennings mind was Trina Kinstler, who wrote sports articles and helped put articles online. "She was sitting on a ledge where we kept newspapers and tears started streaming down her face," Jennings said. "She took it harder than everyone I think." Jennings explained how Kinstler stayed until the very last moment to make sure the entire last issue was posted to the web. "She stuck to the ship until the ship went down," Jennings said. While the paper did have a short existence, Butler feels it had an impact on the way the Enquirer covers Northern Kentucky. "The challenge we put forth was accepted by the competition," Butler said in his closing remarks published in the last issue of the Challenger. "Since we began, The Enquirer has tripled its sales and marketing staff and substantially increased its editorial platform, too, in the Northern Kentucky office." The death of the Sunday Challenger was very disappointing to the people who worked there and to the community. Prichard said she felt disappointed and many conveyed the same thing to her. “In the immediate wake of the paper's demise,” she said. “I encountered so many people who told me how sad they were to see the paper cease to exist.”