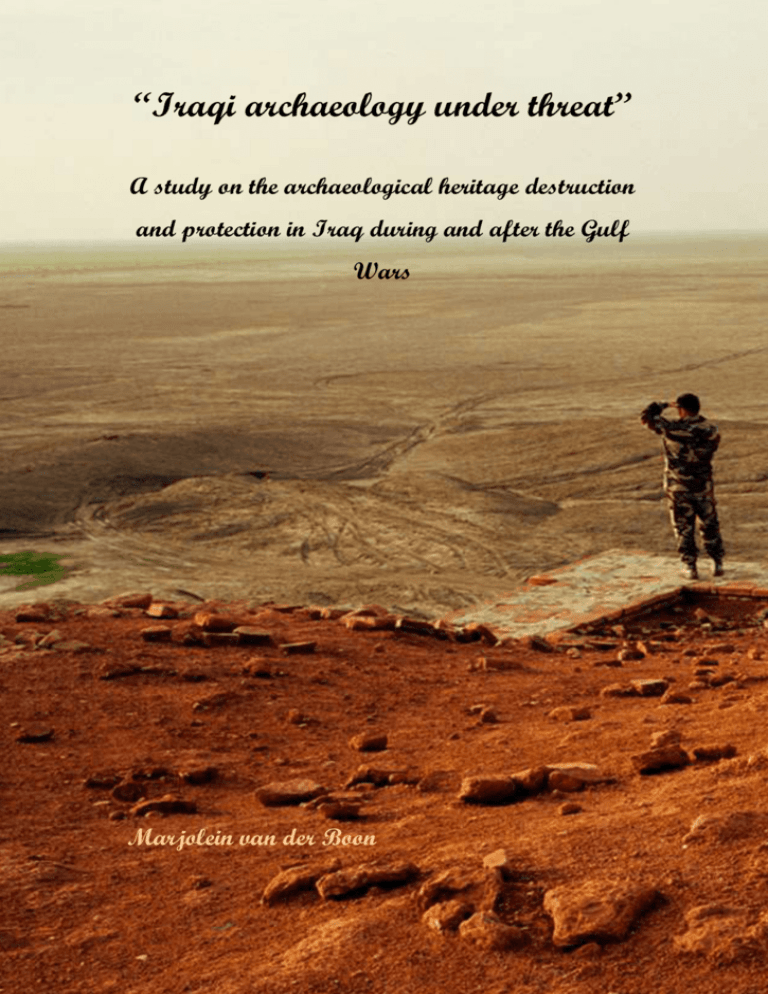

Bachelorthesis

advertisement