The 2001 riots and the emergence of `Community Cohesion`

advertisement

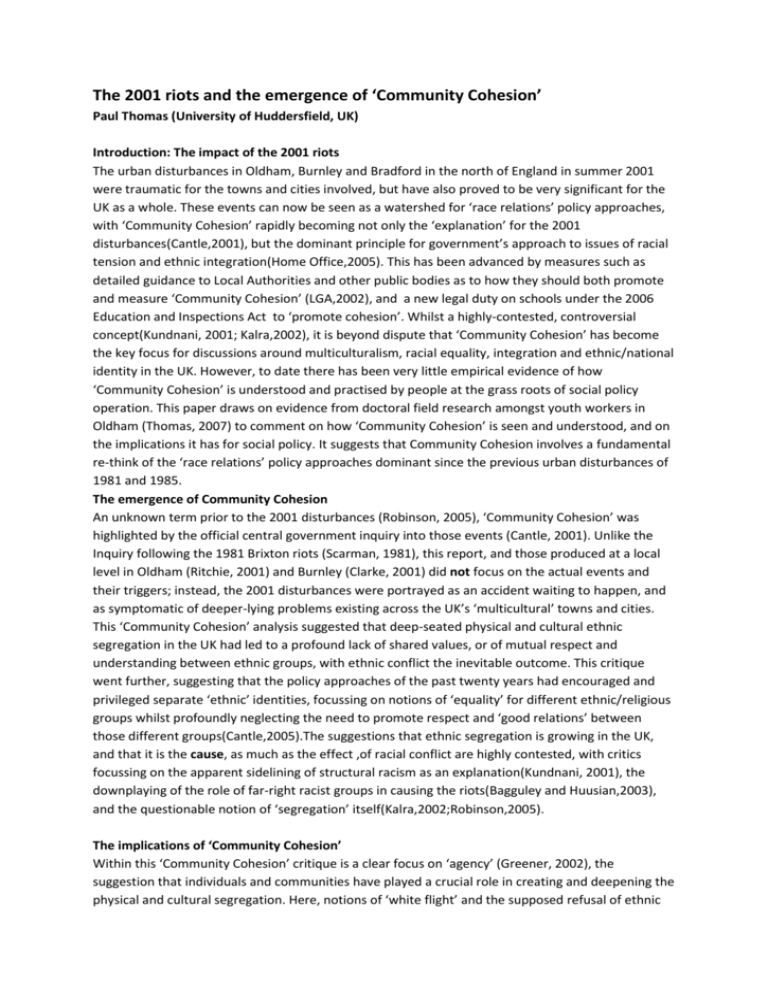

The 2001 riots and the emergence of ‘Community Cohesion’ Paul Thomas (University of Huddersfield, UK) Introduction: The impact of the 2001 riots The urban disturbances in Oldham, Burnley and Bradford in the north of England in summer 2001 were traumatic for the towns and cities involved, but have also proved to be very significant for the UK as a whole. These events can now be seen as a watershed for ‘race relations’ policy approaches, with ‘Community Cohesion’ rapidly becoming not only the ‘explanation’ for the 2001 disturbances(Cantle,2001), but the dominant principle for government’s approach to issues of racial tension and ethnic integration(Home Office,2005). This has been advanced by measures such as detailed guidance to Local Authorities and other public bodies as to how they should both promote and measure ‘Community Cohesion’ (LGA,2002), and a new legal duty on schools under the 2006 Education and Inspections Act to ‘promote cohesion’. Whilst a highly-contested, controversial concept(Kundnani, 2001; Kalra,2002), it is beyond dispute that ‘Community Cohesion’ has become the key focus for discussions around multiculturalism, racial equality, integration and ethnic/national identity in the UK. However, to date there has been very little empirical evidence of how ‘Community Cohesion’ is understood and practised by people at the grass roots of social policy operation. This paper draws on evidence from doctoral field research amongst youth workers in Oldham (Thomas, 2007) to comment on how ‘Community Cohesion’ is seen and understood, and on the implications it has for social policy. It suggests that Community Cohesion involves a fundamental re-think of the ‘race relations’ policy approaches dominant since the previous urban disturbances of 1981 and 1985. The emergence of Community Cohesion An unknown term prior to the 2001 disturbances (Robinson, 2005), ‘Community Cohesion’ was highlighted by the official central government inquiry into those events (Cantle, 2001). Unlike the Inquiry following the 1981 Brixton riots (Scarman, 1981), this report, and those produced at a local level in Oldham (Ritchie, 2001) and Burnley (Clarke, 2001) did not focus on the actual events and their triggers; instead, the 2001 disturbances were portrayed as an accident waiting to happen, and as symptomatic of deeper-lying problems existing across the UK’s ‘multicultural’ towns and cities. This ‘Community Cohesion’ analysis suggested that deep-seated physical and cultural ethnic segregation in the UK had led to a profound lack of shared values, or of mutual respect and understanding between ethnic groups, with ethnic conflict the inevitable outcome. This critique went further, suggesting that the policy approaches of the past twenty years had encouraged and privileged separate ‘ethnic’ identities, focussing on notions of ‘equality’ for different ethnic/religious groups whilst profoundly neglecting the need to promote respect and ‘good relations’ between those different groups(Cantle,2005).The suggestions that ethnic segregation is growing in the UK, and that it is the cause, as much as the effect ,of racial conflict are highly contested, with critics focussing on the apparent sidelining of structural racism as an explanation(Kundnani, 2001), the downplaying of the role of far-right racist groups in causing the riots(Bagguley and Huusian,2003), and the questionable notion of ‘segregation’ itself(Kalra,2002;Robinson,2005). The implications of ‘Community Cohesion’ Within this ‘Community Cohesion’ critique is a clear focus on ‘agency’ (Greener, 2002), the suggestion that individuals and communities have played a crucial role in creating and deepening the physical and cultural segregation. Here, notions of ‘white flight’ and the supposed refusal of ethnic minority communities to engage with the wider culture are crucial, with a particular focus on the use of English and engagement with ‘national ‘culture and values (Cantle, 2001). This has led some to portray ‘Community Cohesion’ as a return to the discredited ‘assimilationism’ of the 1960s (Kundnani, 2001), but, more accurately, it represents a rethinking of ‘multiculturalism’ and ‘antiracism’. Within this focus on agency are clear links to communitarianism (Etzioni, 1995) and the ‘third way’ (Giddens, 1999), suggesting that government cannot engineer a genuinely multicultural society without popular participation. Above all, ‘Community Cohesion’ seems to represent a Putnamesque problematisation of excessive ‘bonding’ social capital, and the need for greater ‘bridging ‘social capital (Putnam, 2000; McGhee, 2003). Inherent in this is a belief that previous policy approaches of multiculturalism and anti-racism have reified and essentialised ethnic/religious identities at the expense of more complex understandings of being and belonging, with policy approaches cementing the cultural and physical barriers created originally by structural and individual racism(Solomos,2003). Here, ‘Community Cohesion’ and associated discussions around ‘Britishness’ can be seen as part of wider attempts by the New Labour government to create ‘cooler’ and more complex/hybrid forms of identity that can replace ‘hot’ forms of ethnic/religious identification(Hall, 2000;McGhee,2005). Field research evidence around ‘Community Cohesion’ Data was drawn from more than 30 in-depth, one to one, semi-structured interviews carried out with youth workers in Oldham during 2005 and 2006. The aim was to explore how ‘Community Cohesion’ has impacted on the assumptions and practice of youth work with young people. The reality of ethnic segregation within Oldham and the role of ‘agency’ in maintaining it was accepted by respondents of all ethnic backgrounds. There was a shared clarity around, and support for, ‘community cohesion’: to respondents, ‘Community Cohesion’ can and must mean ‘meaningful direct contact’ between young people of different ethnic backgrounds, and youth work practice in Oldham has altered substantially to enable this direct contact to take place. Given the tense and racialised nature of Oldham, much of this direct contact across ethnic ‘boundaries’ is significant and ground-breaking, with many parents and communities concerned and suspicious of it. These new approaches have included many shared trips out of Oldham, and a strategic deployment of workers to provide young people with adult role models of different ethnic backgrounds. The aim is to create ‘safe space’ where dialogue and understanding across ethnic/religious can be delivered, so potentially enabling ‘rooting and shifting’, ‘transversal politics’ that allows young people to engage with other cultures and backgrounds without feeling that their own is threatened or disrespected(Yuval-Davis,1997).The clear enthusiasm of youth workers for this new ‘Community Cohesion’ work is partly because it is utilising ‘traditional’ youth work methods of group-based informal activities(Smith,1982) , but is also because of the contrast presented with ‘anti-racism’ as it was understood and practised. ‘Anti-racism’ is viewed as negative, uncreative and counterproductive with many working class white young people (Hewitt, 1996). That said, a significant minority of respondents worried that, in representing a ‘moving on’ from anti-racism, ‘Community Cohesion’ might also represent a retreat from concern with the reality of day-to-day racism (Thomas, 2007). Here, the concern is whether this ‘Community Cohesion’ educational practice with young people is a retreat to the bland and apolitical ‘multiculturalism’ of the past(Chauhan,1990), or a genuinely ‘critical multiculturalism’(May,1999) that allows meaningful dialogue around ethnic identity and tension without privileging or reifying ethnicity above other aspects of personal and collective identity(Hall,2000). References Bagguley, P and Hussain, Y (2003) The Bradford ‘Riot’ of 2001: A Preliminary Analysis, Paper presented to the Ninth Alternative Futures and Popular Protest Conference, Manchester Metropolitan University, 22nd-24th April, 2003 Cantle, T (2001) Community Cohesion - A Report of the Independent Review Team’ London: Home Office Cantle, T (2005) Community cohesion: a new framework for race and diversity, Basingstoke: Palgrave Chauhan, V (1990) Beyond Steel Bands ‘n’ Samosas’ Leicester: National Youth Bureau Clarke, T(2001) Burnley Task Force report on the disturbances in June 2001, Burnley Borough Council: Burnley Etzioni, A(1995) The spirit of community: rights, responsibilities and the communitarian agenda, London: Fontana Giddens, A (1999) The Third Way: The renewal of social democracy, Cambridge: Polity Greener, I (2002) ‘Agency, social theory and social policy’, Critical Social Policy Vol.22 (4) pp 688-705 Hall, S (2000) Conclusion: The multicultural question in Hesse, B (ed.) Un/Settled Multicuturalisms, London: Zed Books Hewitt, R (1996) Routes of Racism – the social basis of racist action, Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books Home Office (2005) Improving Opportunity, Strengthening Society: The Government’s Strategy to increase Race Equality, London: Home Office Kalra, V.S.( 2002) ‘Extended View: Riots, Race and Reports: Denham, Cantle, Oldham and Burnley Inquiries’, Sage Race Relations Abstracts, Vol. 27(4):pp20-30 Kundnani, A(2001), From Oldham to Bradford: the violence of the violated, in The Three faces of British Racism, London: Institute of Race Relations LGA(2002) Guidance on Community Cohesion, London: Local Government Association May, S (1999) Critical multiculturalism and cultural difference: Avoiding essentialism, in S.May (ed.) Critical Multiculturalism, London: Falmer McGhee, D (2003) ‘Moving to ‘our’ common ground – a critical examination of community cohesion discourse in twenty first century Britain’, Sociological Review,51:3 pp366-404 McGhee, D (2005) Intolerant Britain: Hate, Citizenship and Difference, Maidenhead: Open University Press Putnam, R (2000) Bowling Alone- The Collapse and Revival of American Community, London: Touchstone Ritchie, D (2001) Oldham Independent Review – On Oldham, One Future, Government Office for the Northwest: Manchester Robinson, D(2005) ‘The search for Community Cohesion: key themes and dominant concepts of the public policy agenda’, Urban Studies Vol.42(8) pp1411-1427 Scarman, Lord (1981) The Brixton Disturbances of 10-12 April: Report of an Inquiry, London: Home Office Smith, M (1982) Creators, Not Consumers, London: National Association of Youth Clubs Solomos, J (2003) (3rd edition) Race and Racism in Britain, Basingstoke: Palgrave Thomas, P (2007) ‘Moving on from ‘Anti-Racism’? Understandings of ‘Community Cohesion’ held by Youth Workers’, Journal of Social Policy 36:3 pp435-455 Yuval-Davis, N (1997) Ethnicity, gender relations and multiculturalism in T. Modood and P.Werbner (eds.) Debating Cultural Hybridity, London: Zed Books