Cultural Influence on Emotion - ICI/UoP MAIR Student Information

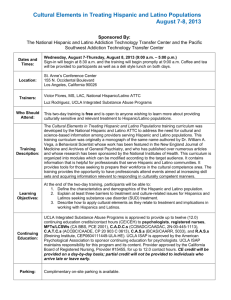

advertisement

CHAPTER 2 REVIEW OF LITERATURE Overview I researched a number of different topics that fell into four general areas: 1) Hispanic/Latino demographic and statistical information and Hispanic/Latino diversity studies including currently accepted terminology; 2) literature describing intercultural concepts and communication styles including power distance, individualism-collectivism, high-low-context, direct-indirect forms of communication, task-relational orientation, and cultural influences on emotion; 3) conflict literature including intercultural conflict styles, face theory, conflict negotiation, conflict resolution, conflict management, and crisis negotiation; 4) Historical, political, ethnic, and socio-economic literature exploring differences and similarities between Colombia, Mexico, and Cuba, plus country-specific information related to the above three areas. Terminology Inherent to Hispanic/Latino intercultural relations is understanding and respect. Thus, it is important that culturally accepted terminology be used to show appropriate respect for the individuals being defined. It is also important to be clear as to who is being defined and by whom. The terms Hispanic culture and Latino culture are many times used to make generalizations about individuals living in the United States who come from, or have origins in, Latin America and Spain. Oboler (1995) says “the ethnic designator Hispanic officially identifies people of Latin American and Spanish descent living in the United States today” (italics original, p. xiii). While the word Hispanic may be the official designator, Albert (1996) notes that Latino or Hispanic is used for persons of Latin American origin or ancestry in the United States, but DeNeve (personal communication, February, 2005) adds that usually Spaniards are not included in the Hispanic/Latino category, but rather are included in the European group. Albert states that while the term Latino is not without problems, “it seems to be currently preferred to Hispanic by members of the culture, in part because it reflects their Latin American origins” (p. 328). Yankauer (1987) says, “inconsistency in terminology over time has already created complications for both researchers and government agencies” (p. 16). Because of the lack of agreement in terminology, the terms Hispanic, Latino, and Hispanic/Latino are used by authors, interchangeably, somewhat indiscriminately, and sometimes without regard to nuance. For consistency and optimal inclusivity, I have chosen, whenever possible, the designator Hispanic/Latino to reference any person of Spanish, U.S. American, Mexican, Central American, South American or Spanishspeaking Caribbean origin living in the United States. Demographic Trends The face of U.S. America is currently being transformed. According to U.S. Census 2000, 35.3 million people identified themselves as Hispanic, a 57.9 percent increase from 1990. The Pew Hispanic Center (2004) adds that the Census 2000 numbers represent a 142 percent increase over the 1980 census count; Hispanic/Latinos are now nearly 13 percent of the U.S. population. Moreover, this percentage, states Rosenfeld (2001), will rise to about 26 percent by 2050 (p. 161). In terms of the labor force, Suro 2 and Passel (2003) say that the number of Latino workers is projected to increase by 12.6 million by 2020, while the far larger non-Hispanic labor force will increase by 11.6 million (p. 7). These numbers not only illustrate major changes in the ethnic makeup of the United States, but also the transformation of the Hispanic/Latino population itself. The fastest Hispanic/Latino growth today, says Logan (2001), are among “New Latinos” (p. 1). “New Latinos,” as defined by Logan, are “people from the Dominican Republic and a diverse set of countries in Central America (such as El Salvador) and South America (such as Colombia)” (p. 1). Based on Census 2000 and related sources, Logan estimates that “the number of New Latinos has more than doubled since 1990, from 3.0 million to 6.1 million (p. 1). Hence, current immigration trends and demographic shifts are not only adding to the overall diversification of the United States, they are also creating greater diversidad within the Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, bringing diverse Hispanic/Latinos together at increasing levels. “The New Latinos,” echoes Logan, “bring a new level of complexity to the rapidly changing complexion of ethnic America” (p. 1). This complexity creates a significant need for Hispanic/Latino intercultural research. However, Hispanic/Latinos continue to be treated as one whole. Altarriba and Bauer (1998), for example, state that “although it would be helpful to provide a typical worldview for Cuban Americans, Mexican-Americans, and Puerto Ricans, individually, there is no distinction among the groups’ worldviews in the literature” (p. 395). Oboler (1995) sums up the simplification problems saying: In the current usage by the US Census, government agencies, social institutions, social scientists, the media, and the public at large, the ethnic label Hispanic obscures rather than clarifies the varied social, and political experiences in U.S. 3 society of more than 23 million citizens, residents, refugees, and immigrants with ties to Caribbean and Central and South American countries. (p. 51) Intercultural scholars and researchers have recognized both the internal diversity of Hispanic/Latino culture and the need for greater research into understanding differences between Hispanic/Latino groups. For example, Albert (1996) states that what is needed is “a lot more work on the variations that may exist among Latin Americans and Latino groups” (p. 331); Hayes-Bautista and Chapa (1987) recognize that “there are vast differences between different national origin Latino groups” (p. 66); and TingToomey and Oetzel (2001) say that “with the tremendous diversities under the Latin American label, we will do well to increase the complexity of our understanding of the values and distinctive . . . patterns of each group” (p. 53). Despite an acknowledged need, my literature review revealed intercultural research that lumps Hispanic/Latinos together as one body when discussing a variety of intercultural topics. For example, Albert (1996), Delgado (1981), Marin and Triandis (1985), and Triandis (1983) all generalize Hispanic/Latino cultural patterns without internal distinction. Hammer and Rogan (2000) offer similar treatment in discussing Hispanic/Latino conflict negotiation patterns, as does Lotito (1988) when discussing Hispanic/Latino communication patterns. When studies that I surveyed did specify a particular Latino national culture group, it did so to make a comparison to a non-Hispanic/Latino group such as Condon’s (1988) research on communication style differences between Mexicans and North Americans. More often, however, the comparisons were made on the ethnicity level, such as Collier’s (1988) study comparing Mexican American, European American and African American conflict competence and negotiation patterns; Martin, Hammer, and Bradford’s 4 (1994) study on communication competence behaviors between Hispanics and nonHispanics; and Hecht, Ribeau, and Sedano’s (1990) study on the Mexican American perspective on interethnic communication. Some literature that I surveyed provides research regarding one Latin-American culture, for example, Diaz-Royo’s (1974) study on Puerto Ricans, Queralt’s (1984) study on Cubans, and Diaz-Guerrero and Szalay’s (1991) and Garcia’s (1996) study on Mexicans. With the exception of non-academic travel guides offering cursory treatment of intercultural themes, Stephenson’s (2003) book on South Americans, Lederach’s (1991) study of the folk language of conflict resolution in Central America, Adler and Garaitonandia Tapie’s (1998) article on Latin American communication barriers, and Johnson, Lindsey and Zakahi’s (2002) study on Anglo American, Hispanic American, Chilean, Mexican, and Spanish perceptions of competent communication, were the only bodies of literature that I found that made inter-Hispanic/Latino comparisons. Finally, while research related to intercultural conflict style and conflict resolution abound, such as Hammer (1997) and Ting-Toomey (1985), to date, I have not identified any research studies that measure inter-Hispanic/Latino conflict style and conflict resolution variance containing research sample populations of discreet country origin. Intercultural Conflict Styles Ting-Toomey (2004) defines conflict style as “the general behavioral tendencies used during the actual conflict negotiation process” (p. 225). Hammer (2003) adds that conflict style “can be viewed as a stable ‘interpretive frame’ for understanding and responding to one another’s intentions, motives, and actions” (p. 16). He adds that this interpretive frame “is generated from the manner in which contending parties 5 communicate with one another around substantive disagreements and the manner in which they communicate how they feel toward one another (affective or emotional response)” (p. 16). To extend this definition, intercultural conflict style, according to Hammer refers to “a culture group’s preferred manner for dealing with disagreements and communicating emotion” in a given situation within a given relationship (p. 16). The most significant body of research that I have found that makes interHispanic/Latino comparisons within the conflict arena is The Intercultural Conflict Styles Inventory (ICS) developed by Hammer (2003). This served as a starting point for the literature review. Hammer’s model is developed around two scales. The vertical scale measures an individual’s communication style in terms of directness or indirectness. The horizontal scale measures an individual’s emotional style in terms of emotional restraint or expressiveness. Hammer explains that individuals use “different conflict resolution strategies depending on whether their conflict communication style is more direct or indirect” (p. 7). He lists a set of patterns that embody each style. Hammer also explains that individuals use different conflict resolution strategies if they are “more emotionally expressive or emotionally restrained” (p. 7). He lists a set of patterns for both emotional expressiveness and emotional restraint (See Appendix A for more information on these sets of patterns). The direct-indirect scale and the emotionally expressive-restrained scale form a quadrant with each quadrant representing a conflict style. After taking the inventory, an individual can find out their preferred conflict style. The four conflict styles are: Discussion, Accommodation, Engagement, and Dynamic (see Appendix B). The Discussion style emphasizes the use of direct communication and a controlled emotional 6 response for dealing with disagreement. The Accommodation style stresses a more indirect communication strategy and a controlled emotional response for dealing with disagreement. The Engagement style describes a direct communication style and an emotionally expressive response to handling disagreement. Finally, the Dynamic style involves an indirect communication strategy and an emotionally expressive response to disagreement. What interested me most about these conflict styles was that in a table found on the final page of Hammer’s (2003) Intercultural Conflict Style Inventory’s Interpretive Guide (see Appendix C), he provides a summary of how disagreements are managed and emotions expressed across cultures. According to this summary, Latin American countries were placed into two separate quadrant areas. Latin American countries such as Mexico, Peru, Costa Rica, and Argentina were placed in the Accommodation Style quadrant area (indirect-emotional restraint). Latin American countries such as Cuba and Puerto Rico were placed in the Engagement Style quadrant area (direct-emotional expressiveness). Thus, according to this summary, certain Latin American individuals have conflict styles diametrically opposite to the conflict styles of other Latin American individuals. Therefore, members of some Spanish-speaking Latin American countries may have opposite preferences in dealing with disagreements and communicating emotion than those of other Spanish-speaking Latin American countries. These results are interesting given the treatment of Hispanic/Latinos as one cohesive body, who continue to be brought together in social and work settings due to their common language, and other related factors, such as political solidarity, and status as newly acculturating immigrants. 7 In his ICS model, Hammer (2003) does not account for the Latin American country placements into specific conflict style quadrant areas outlined in Appendix C. Examination of the demographic summary of his sample population of 510 respondents reveals few Latin Americans. Only six people (one percent) spent their formative years in Central America. No respondents are mentioned as spending their formative years in the Caribbean. Sixty-two people (13 percent) spent their formative years in South America. And while 266 of the respondents (56 percent) indicated having spent their formative years living in North America, it is unclear how many of those came from Mexico. Overall, 71 of the 510 respondents (16 percent) indicated their cultural background as Latin American, but no country-specific information was collected. In a second study of an additional 487 respondents, 116 people (26 percent) indicated that they were citizens of countries other than the United States. Unlike the first sample, Hammer (2003) did not collect information as to where respondents lived during their formative years. Instead, he collected country of citizenship information, and respondents were given an option as to whether to provide this information or not. Of those respondents who did provide country of citizenship information, few respondents indicated Latin American citizenship (Venezuela [n = 1]; Dominican Republic [n = 1]; Mexico [n = 1]; Peru [n = 1]). Neither of Hammer’s (2003) studies places specific Latin American countries into specific conflict style categories. Hammer’s justification for regional cultural placement (e.g., Mexico in Accommodation or Cubans in Engagement), is based on his examination of previous literature, which is not specifically cited in his research material on the ICS. 8 High- and Low-context Communication Patterns I found no comparative literature that measured direct-indirect communication style similarities and differences of different Latin American countries. Directness and indirectness are inherent parts of Hall’s (1991) high-context and low-context communication theory. According to Hall, high-context communication emphasizes how intention or meaning can best be conveyed through context and nonverbal channels. Ting-Toomey (1985) states that high-context communication refers to communication patterns of indirect verbal mode. Hall (1976) identifies Latin American culture as highcontext and cites as examples both Mexico and Cuba. While relevant, it does not explain the country-specific Hispanic/Latino direct-indirect distinctions that Hammer (2003) reports. Emotional Expressiveness and Emotional Restraint In terms of emotional expressiveness-restraint, I identified a key cross-cultural research study by Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (1998) of over 30,000 participants in 49 countries. They measured, among other things, how reason and emotion play a role in relationships between people. Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner define members of cultures that show emotion as affective and members of cultures that do not show emotion as neutral. They say: Members of cultures which are neutral do not telegraph their feelings but keep them carefully controlled and subdued. In contrast, in cultures high in affectivity, people show their feelings plainly by laughing, smiling, grimacing, scowling and gesturing; they attempt to find immediate outlets for their feelings. (p. 70) Results from the 49 countries surveyed show Spain fourth, Cuba fifth, and Venezuela seventh, in terms of emotional expressiveness. Mexico scored 26th indicating a lesser 9 degree of emotional expressiveness (p. 71). However, there is no specific link made between emotional affectivity-neutrality and conflict. Cultural Influence on Emotion In order to obtain a solid understanding of the cultural influence on emotion, I located several critical articles whose terminology and ideas have been used by intercultural scholars in research on intercultural conflict. Ekman (1972) and Friesen (1972) coined the term display rules to account for differences in the expression of negative emotion, and Mesquita and Frijda (1992) added, cultures differ in display rules and feeling rules, and these rules may apply to emotional spontaneity and expressive display in general, as well as to the feeling and displaying of emotions in particular situations or with aspect to particular types of emotion. (p. 199) Ting-Toomey and Oetzel (2001) validate the connection between emotion and conflict, concluding that “cultural display rules exist in conflict which regulate displays of aggressive or negative emotional reactions such as anger, fear, shame, frustration, resentment, and hostility” (p. 54). Following Hammer’s (2003) placement of some Latin American countries in different quadrant areas, one could conclude that different cultural display rules exist between members of different Latin American countries. However, Hammer (1997,2002, 2003) and Hammer and Rogan (1997) consistently state that Hispanic/Latino’s control over negative emotional expression is critical to conflict resolution (i.e., emotional restraint). Therefore, it is still unclear whether similarities and differences exist. If they do exist, it is unclear how any potential cultural display-rule similarities or differences (such as emotional restraint or expressiveness for members of different Latin American countries) might affect the Hispanic/Latino conflict dynamic; 10 how they might act as conflict trigger points; or how they might cause a conflict to escalate between two individuals. Perhaps there are measurable differences in emotional expressiveness and restraint among members of various Latin American countries. However, it may be that these differences are irrelevant factors to understanding Hispanic/Latino conflict. I have not found any research to support or disprove a relationship. Historical Foundations for Understanding Latin American National Culture Similarities and Differences Vaahterikko-Mejia (2001), states that “national culture, where a person has been born, has grown up, and educated is of utmost importance in her/his decisions, value systems, the way of perceiving the environment, the way of communicating and way of work” (p. 24). Therefore, in order to prepare for my research, it is important to examine similarities and differences presented in the literature, and to discuss the historical context that serves as a baseline for exploring both commonalities and variations across the Hispanic/Latino Diaspora. Focusing on Colombia, Mexico, and Cuba, I will introduce Latin American historical information from colonial to modern times, tying the historical facts of the past to cultural variables of the present-day. While this historical treatment is by no means exhaustive, it offers a foundation for understanding some underlying influences impacting cultural similarities and differences that exist in Latin America. National and regional similarities and differences may be due to culturally distinct racial and ethnic roots. History has mixed pre-colonial indigenous cultures, with 11 European and African cultures from colonial times, and present day immigrants. Lotito (1988) says that in Latin America there are three cultural regions: the mestizo (Indian + Spaniard) common to Mexico, Central America, and western (or Andean) South America, that of the European or primarily Caucasian population of eastern and central (non-Andean) South America, which has been increased by large immigrations from western Europe in this century [20th century], and the third of the Caribbean mulato (Indian + Spaniard + African) . . . within the Spanish-speaking Caribbean Islands. (p. 34) Each of these three cultural/geographic regions has its own colonial history. In the Caribbean region, according to Lotito, the indigenous died out rapidly, succumbing to smallpox and other diseases soon after the Spanish arrival, and then Africans were brought in as slaves to cultivate sugarcane and tobacco. The Andean countries, including Colombia, and the central plateau regions, including Mexico, were colonized 20 to 50 years later than the Caribbean when there was more resistance to the diseases introduced by the Spaniards. Additionally, due to the more structured lifestyles of the highly developed indigenous populations of this area, individuals were more resistant to the heavy labor forced upon them. Subsequently more indigenous peoples and their cultures survived. Finally, the indigenous tribes of the east coast of South America were more nomadic and less evolved, and the few that survived were insufficient to produce much of a racial mix. So, except for Brazil, this region is mostly Caucasian in origin (p. 34). In the last 100 years, according to Marin and Marin (1982), South American countries like Argentina and Chile have received heavy European migration waves that shaped cultural values. This variety in indigenous, African, and European cultures, say Archer and Fitch (1994), exerts strong influence on Latin America. The influential elements, says Lotito (1988), include religion, values, patterns of interaction and linguistic blending. 12 The Catholic Church has had a strong influence on Latin America and was a primary vehicle for disseminating European culture to indigenous populations during the conquest of (what would become) Latin America by the Spaniards. During colonialism, says Stephenson (2003), the Catholic Church played an important role in expanding the power of the Caucasian conquerors by disseminating spiritual concepts and values (p. 33). Today, Roman Catholicism is the primary religion of Latin America and the Catholic Church’s influences are present down to Latin Americans’ cultural core. Colina-Diez (2004) refers to Latin America as the “Catholic continent” and says that Latin America’s 400 million Catholics make up 42 percent of all Catholics in the world (p. 1). IberoCatholic cultural influences include, according to Queralt (1984), the primacy of family and fatalistic acceptance. Foster (2002) adds that the traditions of the Roman Catholic hierarchy still play a powerful role in Latin America in determining decision-making authority in social, civic, and workplace settings through rigidly prescribed formal rules. However, Catholic influences are stronger in some Latin American countries than in others. For example, Catholicism, says Vaahterikko-Mejia (2001), has the least influence in Cuba. Unlike other regions of Latin America, the Caribbean region has strong African religious influence. Cramer (2000) says that in Cuba, Santeria is a widely held belief, especially among black residents and Queralt adds that Santeria rose out of the combination of African slave and Spanish Catholic religious beliefs and rituals during the colonial period (p. 117). Unlike the Cuban Afro-European cultural union typified by Santeria, Mexican culture, according to Foster (2002), is a combination of pre-Colombian indigenous beliefs, Roman Catholicism, and modern European secular elements (p. 13). Foster states 13 that in Mexico, the racial and cultural mixture, know as la raza (race), is one of the primary distinctions between Mexico, of which most Mexicans are very proud, and much of the rest of Latin America (p. 13). Pride in la raza has included, according to Stephenson (2003), the open incorporation of the indigenous presence into mainstream Mexican culture and society. Stephenson adds that Mexico is distinct from the rest of Latin America because this open incorporation has not happened to the same extent elsewhere in Latin America (p. 12). While Mexicans may not reject their indigenous roots, hierarchical distinctions along racial lines are found in Mexico as in other parts of Latin America. During the colonial period, says Stephenson (2003) People of mixed ancestry were positioned in the middle tiers of the hierarchical social structure – between the Caucasians at the top and the Native Americans and Africans at the bottom. After independence, and even into the contemporary period, this social placement has generally continued. (p. 29) The patron system is an historical example of class inequality. Archer and Fitch (1994) note that from the colonial period to the very recent past, the patron system, which unequally linked plantation owners to tenant workers, has left a legacy throughout Latin America that clearly distinguishes the needs of the middle and upper classes from lower status persons (p. 79). However, in contrast to this, Foster (2002) asserts that Cuba’s recent history, namely the Cuban Revolution, continues to color the Cuban value system. Foster states that formal Latin traditions from the conquest were rejected by the Revolution, and there is an egalitarian and respectful informality that permeates relationships. In contrast, in Colombia, according to Foster, and in Mexico, according to DeNeve (personal communication, February, 2005), hierarchy and power are still rigidly determined. They say that the Churches in Colombia and in Mexico are especially 14 conservative and tied to the privileged class. In Cuba, titles are not typically critical. In contrast, Foster says that Colombia is perhaps the most formal, most reserved, and most closely related with the traditions of fifteenth-century “conquistador” Spain. This is largely due to the fact that Spain set up its first viceroy in the New World in what became Bogotá, the current capital of Colombia. Stark contrasts between African-influenced Cuba, and Roman Catholic/Colonialinfluenced Colombia can also be seen in terms of communication style and conflict style. Foster (2002) reports that in Colombia, the importance of hierarchy requires careful speech, and “speaking one’s mind, especially at work, is done carefully” (p. 96). Foster says the only exception to this would only be with one’s most trusted friends. In contrast, Queralt (1984) reports that Cubans treat one another informally, even when not acquainted, and he attributes their informal sociability and gregariousness to Cuban black cultural roots (p. 118). Finally, Kochman (1981) notes a link between the “high-keyed: animated, interpersonal, and confrontational” (p. 18) African-American conflict style pattern to that in Cuba, saying that the African-American patterns and perspectives have also been found among blacks in the Caribbean (p. 14). Hispanic/Latino Value Orientation Similarities In general, the literature consistently shows that Hispanic/Latinos have an interpersonal orientation. Albert (1996) considers the interpersonal orientation as the meta-orientation of Latin Americans that permeates many facets of life such as patterns of communication, the value of respect and harmony in relationships, and behavior in the workplace. Several value orientations help to frame the interpersonal orientation, including collectivism and high-context communication. 15 Collectivism Hispanic/Latino cultures have been found to be consistently collectivistic in nature. Hofstede (1991) defines collectivist societies as those in which “people from birth onwards are integrated into strong, cohesive in-groups, which throughout people’s lifetime continue to protect them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty” (p. 260). Triandis (1995) adds that collectivism promotes relational interdependence, in-group harmony, and in-group collaborative spirit. Hofstede found high collectivistic index values in Guatemala, Ecuador, Panama, Venezuela, Columbia, Costa Rica, Mexico, and Peru (p. 53). Collectivistic harmony also extends to conflict situations. Ting-Toomey (1999) states that for collectivists, the masking of negative emotions is critical to maintaining a harmonious front during conflict. In the context of traditional Hispanic/Latino Americans’ conflict practices, Garcia (1996) and Padilla (1981) note that tactfulness and consideration of others’ feelings are considered to be important norms in interpersonal confrontation situations. Tactfulness and consideration of others’ feelings are conveyed, says Ting-Toomey (1999), through the use of accommodating and other-concern facework rituals (p. 217). Ting-Toomey also discusses collectivist norms for conflict resolution. She says conflict is effectively resolved when both parties help to attain mutual face saving while reaching a consensus on substantive issues between them. In addition, a conflict is appropriately managed when both sides acknowledge the expectations of the relevant in-groups and give honor and attention to the in-groups’ needs. To collectivists, continues Ting-Toomey, a conflict solution has group-based and long-term implications (p. 220). 16 Connectedness Tied to Hispanic/Latino collectivism is the importance of having and maintaining connections. Archer and Fitch (1994) discuss the Colombian phenomenon palanca (literally, a lever; interpersonally, a connection) (p. 83). In using a palanca, Colombians use “a relationship like a tool to obtain some objective” in order to “transcend scarcity and/or rules” (p. 84). Archer and Fitch state that palancas rest fundamentally on an interpersonal connection between a provider and a beneficiary with the provider being at an equal or higher status than the beneficiary (p. 85). However, they say, some degree of confianza (hope, trust, familiarity, confidentiality), must be created in order to seek the benefits of the connection. Other authors report on similar concepts in other Latin American countries. DeNeve (personal communication, February, 2005) reports the presence of palancas in Mexico as very common, especially in politics. According to Lederach (1991), in Costa Rica the concept of connections is called patas (literally feet; symbolic of using a connection for an action-based purpose), enchufe (plug-in) in Spain, and cuello (literally neck; symbolically, the connection between head and heart) in Honduras and throughout Central America. Connectedness has important connotations for conflict resolution in Latin America. Lederach (1991) researched conflict resolution in Central America and found that conflicts are always viewed as being embedded in the social network. In his observation, he found that “the single most important characteristic affecting both the understanding and resolution of conflict is a person’s network (p. 168). Lederach states that the best Central American term for describing conflict is estamos bien enredados (we 17 are all entangled), built around the Spanish word red (fisherman’s net). He adds that this image is one of knots and connections, an intimate and intricate mess. A net, when tangled, must slowly and patiently be worked through and undone. When untangled it still remains connected and knotted. It is a whole. A net is also frequently torn leaving the holes that must be sewn back together, knotting once again the separated loose ends. (p. 168) This is an excellent metaphor for better understanding the conflict resolution process for Hispanic/Latinos including the use of a third-party intermediary in the resolution process. Extending the metaphor, Lederach explains that many times a third person, el tercero (the third) is the connector between the separated loose ends that helps sew the net back together. Their connection, unlike a mediator, is based on a personal relationship, not a professional function or written contract. Lederach says that an individual will go to someone in his or her network with whom he or she has confianza and who, also has confianza with the other entangled person (p. 177). Lederach explains that el tercero serves as un consejero (trouble-shooter, go-between) between the individuals (p. 169). In summary, successful resolution, says Lederach, reaffirms that Latin Americans are part of a larger whole. Simpatía In Hispanic/Latino cultures a concept called simpatía embodies the harmonious spirit of collectivism. Triandis, Marin, Lisansky, and Betancourt (1984) say that simpatía refers to a permanent personal quality where an individual is perceived as likable, attractive, fun to be with and easygoing. An individual who is simpático shows certain levels of conformity and an ability to share in others feelings, behaves with dignity and respect toward others, and seems to strive for harmony in interpersonal relations. (p. 1363) 18 According to Alum and Manteiga (1977), for Cubans, being antipatico (unlikable, unwitty, disagreeable) is “the worst of all cultural sins” (p. 12) and ignoring simpático, add Triandis et al, leads to stress and discomfort. Triandis et al. say that simpatía “implies a general avoidance of interpersonal conflict and a tendency for positive behaviors to be emphasized in positive situations and negative behaviors to be de-emphasized in negative situations” (p. 1363). Hispanic/Latinos manage this through the use of high-context communication and avoidance strategies. Avoidance Another manner in which many Hispanic/Latinos maintain harmony is by masking negative feelings. This is done through avoidance. Mexican Nobel Laureate, Octavio Paz (1985) writes, “The Mexican . . . seems to me to be a person who shuts himself away to protect himself: His face is a mask and so is his smile. Everything serves him as a defense: silence and words, politeness and disdain, irony and resignation” (p. 29). A general survey of the literature uncovers avoidance as a conflict management strategy for collectivists including Hispanic/Latinos. Ting-Toomey (2004) states that avoiding facework emphasizes the preservation of relational harmony by not directly dealing with the conflict up front (p. 227). Triandis et al. (1984) report that the value that Hispanics and Latin Americans place on the avoidance of negative behaviors such as criticizing, insulting, fighting etc. has also been widely documented including Diaz-Royo (1974) Fitzpatrick (1971), and Madsen (1972) (p. 1364). In particular, Stephenson (2003), says that South American Spanish-speakers are usually quite careful in their conversations not to bring up anything that might be construed by another as personally 19 offensive or hurtful in order to avoid a potentially explosive situation, even if such avoidance leads to greater complications later (p. 63). Diaz-Guerrero (1975), states that Mexicans seem to feel that the best way to resolve problems is to modify oneself rather than to modify the physical, interpersonal, or social environment (xviii). In a study comparing the conflict resolution styles of Mexican-American and Anglo-American children, Kagan, Knight and Martinez-Romero (1982) found that “the early response of Mexican children [to conflict] is very predominantly a non-conflict response” (p. 55). However, they found that “they then develop away from that orientation and increase both mediated and direct conflict” (p. 55). Kagan et al. explain that the implication of their study’s results is that the Mexican American children, compared to Anglo-American children are less likely to create a conflict, but are equally likely to respond to conflict with conflict or mediated conflict. High-Context Communication In general, Latin American cultures’ communication patterns have been found to be high-context, and as mentioned above, high-context communicators use an indirect as opposed to direct communication style. Hall (1991) says that high-context transactions are more on the feeling, intimate side where little information is explicit and coded (p. 61). Paz (1985) provides a literary translation of this concept. He writes that the Mexican’s “language is full of reticence, of metaphors and allusions, of unfinished phrases, while his silence is full of tints, folds, thunderheads, sudden rainbows, indecipherable threats. Even in a quarrel he prefers veiled expressions to outright insults” (p. 42). By protecting an individual from the emotional discord that conflict triggers, a high-context, indirect communication strategy promotes harmonious relationships 20 important to collectivists. According to Olsen (1978), in any system, conflicts occur primarily for either “instrumental” or “expressive” reasons (p. 308). Olson says that instrumental conflict is marked by “opposing practices or goals,” and expressive conflict stems mainly from “desires for tension release, from hostile feelings” (p. 308). TingToomey (1985) states, “high-context culture individuals have a much more difficult time in objectively separating the conflict event (i.e., instrumental conflict) from the affective domain (i.e., expressive conflict). For them, the conflict issue and the conflict person are the same, hardly separable from each other” (p. 78). So, high-context strategies are used to indirectly address conflict while maintaining harmony. Alum and Manteiga (1977) provide an example. They say that “Cubans’ hostility is more often than not channeled through jokes and wit, which everyone is expected to accept in good sport as a sign of being simpático” (p. 12). This is an example of how Hispanic/Latinos may be able to avoid negative communication while still addressing the conflict, albeit indirectly. Hispanic/Latino Value Orientation Differences Having looked at many cultural values and behaviors that are common among Hispanic/Latinos, now we must look at cultural values and behaviors that differ among Hispanic/Latinos. The identification of Hispanic/Latino differences, such as inter-ethnic conflict style differences, are useful in many ways including explaining some reasons affecting inter-ethnic conflict in the United States. However, greater fidelity is called for in order to identify possible causative Hispanic/Latino conflict variables. In thinking of Hispanic/Latino conflict, several questions come to mind. First, are some Hispanic/Latino groups more likely to create conflict than others? Second, if Hispanic/Latinos are, in general, more likely to choose a non-conflict response (i.e., avoidance) than a conflict 21 response, what are the factors that trigger a conflict response? Third, is conflict more or less likely in certain contexts than in others? Fourth, if resolution involves mediation, what does the mediation process look like? Below, I discuss an important Hispanic/Latino value orientation difference that I have identified, through discussions with informants, as crucial to the Hispanic/Latino conflict dynamic, which helps to begin to shed light on some of these questions. Power Distance Hofstede (1991) defines power distance as “the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally” (p. 28). Dahl (1957) defines power as the ability to influence the behavior of others, often due to the control of resources. Hofstede measured power distance variance across 53 countries in a study of middle managers working for a large multinational company. Of those countries surveyed, Guatemala ranked second, Mexico fifth, Venezuela sixth, Ecuador eighth, Brazil 14th, Colombia 17th, El Salvador 18th, Peru 21st, and Uruguay 26th. However, not all Latin American countries scored high in power distance. Argentina’s 35th, and Costa Rica’s 42nd ranking indicate low power distance values. Additionally, according to Cramer (2000) Cuba has a low power distance value. So while Hofstede’s power distance index shows high values for many Latin American countries, unlike his collectivism index, his power distance index shows a wide degree of power distance variance. There is a strong link between power distance, hierarchical status, class, and behavior. According to Schwartz (1994), in hierarchical cultures social structure is differentiated by ranks as opposed to being flat, and Brett (2003) says that in hierarchical 22 cultures, social status implies social power. In terms of class, Garcia (1996) says that class position includes implications of such things as educational level, financial standing, and social influence; and according to Hofstede (1991), “in most societies, social class, education level, and occupation are closely linked” (p. 28). The important distinction to be made between hierarchy, class, status, and power distance is that while, according to Hofstede, “there is inequality in any society” (p. 23), “power distance reflects the range in which various countries handle the fact that people are unequal” (p. 24). In high power distance countries, individuals accept hierarchical and class differences and their own and others’ status within it. In order to describe the individual’s place within a power distance culture, the term vertical self-construal is used. Ting-Toomey (1999) says that “individuals who emphasize vertical self-construal would prefer formal, asymmetrical interactions (i.e., differential treatment), with due respect to people with high-status positions, titles, and the special occasion” (p. 208). Oetzel et al. (2001) add that members of large power distance cultures make clear distinctions between lower and higher status individuals. Ting-Toomey provides an excellent example of this. She states that in small power distance cultural situations, children can contradict their parents and speak their own minds, while in large power distance cultural situations, children are expected to obey their parents. She adds that the value of respect between unequal status members in the family is taught at a young age. Power Distance and Conflict Power Distance affects the conflict dynamic between individuals of higher and lower status. Leung (1997) says that “conflict between members of different social ranks 23 is likely to be less frequent in hierarchical than egalitarian cultures (p. 303). However, it cannot be assumed that this is due to mutual good feeling and good behavior. For example Brown and Levinson (1987, as quoted in Oetzel et al., 2001, p. 241) proposed that “the more power individuals have, the less polite they are,” and Lim and Bowers (1991) found that the more power an individual had, the less likely they were to use tactful facework. Facework, according to Ting-Toomey (2004) refers to “the specific verbal and nonverbal behaviors that we engage in to maintain or restore face loss and to uphold and honor face gain” (p. 218). Ting-Toomey has proposed a number of different facework strategies, some of which are more prevalent in certain cultures than others. TingToomey has identified three facework strategies: dominating (e.g., aggressive behaviors), avoiding, and integrating (e.g., compromising). In a cross-cultural study investigating face and facework during conflicts across four national cultures, Oetzel et al. (2001) found that power distance had small, positive effects on avoiding and dominating facework. They said that while dominating and avoiding facework are seemingly contradictory, “it may be due to the power individuals feel they possess. If people have power, they can do what they want” (p. 254). Triandis et al. (1984) also acknowledge this seeming contradiction to harmoniousness and simpatía. They say that deviations from the simpatía script may be moderated in the case of a high-status person, who can engage in more superordinate behaviors, without rejection from others, because of the operation of the power distance script. Thus, while “good behavior” and being simpático may be salient goals for Hispanic/Latino relationships, the power distance script launders “bad 24 behavior.” Its allowance maintains relational harmony while managing and limiting vertical conflict. While power distance limits a lower status individual’s ability or willingness to participate in conflict with a higher status individual, it is likewise a systemic tool available to lower status individuals as a vehicle for managing and resolving conflicts with other individuals of equal status. Ting-Toomey (2004) explains that in many collectivistic, high power distance cultures, conflict is often managed by a third party mediator from a high-status position, and therefore has a credible reputation. However, Lederach (1991) discusses the third-party intervention process for Central Americans as informal and tied to a person’s interpersonal network, noting that confianza is a necessary component that ties the third party to both parties in conflict. However, Lederach states that confianza takes place between only a select few in the network, and is reserved for intimate friends and family. Thus, it is unclear whether there is a connection between power distance and third-party mediation. Power Distance and Respeto The everyday enactment of power distance is infused into the very core of Hispanic/Latino cultures through the very rules of the Spanish language. Garcia (1996) explains that the Spanish pronoun usted is the formal application of the English pronoun you, while tú is the informal application of the same pronoun. In a study on the usage of tú and usted by Covarrubias (2002), participant explanations of usted systematically cooccurred with references to the concept of respeto (respect). Garcia (1996) says that respeto is the Latin American version of Ting-Toomey’s (2004) notion of face. Covarrubias (2002) defines respeto as 25 (1) respecting another person’s rights; (2) acknowledging persons based on their age, rank, social, and/or economic standing; (3) protocol; (4) obedience to authority; (5) speaking in well-mannered ways (i.e., no cursing or swearing); and (6) not injuring or insulting another person. (p. 89) This definition begins to show the dynamic, complex aspects of respeto, which is only partially akin to the English equivalent – respect. Covarrubias states that the concept of respeto transcends the meaning of a single term to encompass a broader culture-sensitive system about the meaning and function of speech. Covarrubias labels this meaning system the Code of Respeto. Code of respeto. By deploying the word usted in conversation, the Code of Respeto is activated. The Code of Respeto has several connotations as noted in the definition. Garcia (1996) categorizes the use of usted into three areas: (1) It implies a power distance element indicative of class maintenance, (2) it creates a status difference that is based on implicit worth, and (3) it reinforces a contextual boundary to a relationship by imposing an implicitly formal communication environment. First, the Code of Respeto implies a power distance element indicative of class maintenance. Through the use of tú or usted during conversation, according to Garcia (1996), “relational players are always aware of their hierarchical position in a relationship” (p. 146) where one person assumes the lower status position and the other assumes the higher status position. For example, a subordinate in the workplace might address his or her superior using the pronoun usted while the superior would respond 26 using tú. Garcia explains, “these interactions not only reinforce a power relationship but also impose a status of inequality” (p. 147). From this perspective, Garcia says The high-class individual is allowed to disagree with much more frequency and force than people who are members of lower classes. For example, this cultural latitude enables high class persons fervently to refute arguments posed by lower class individuals, interact (almost at will) more frequently with people who belong to a perceived lower class, interrupt private conversations without fear, and generally impose a personal will on the immediate environment. (p. 149) Garcia’s statement is in accord with the conclusions stated above by Brown and Levinson (1987, as quoted in Oetzel et al., 2001), Lim and Bowers (1991), Oetzel et al. (2001), and Triandis et al. (1984) regarding behavior and power distance. Second, the Code of Respeto creates a status difference that is based on implicit worth. In this case, Garcia (1996) explains that higher class is granted to people with tangible resources, such as to elders for their experience, to teachers for their willingness to share knowledge, and to doctors for their medical expertise. Third, the Code of Respeto reinforces a contextual boundary to a relationship by imposing an implicitly formal communication environment. Respetuoso (respectful) speech is highly formalized. Covarrubias (2002) says that Code of Respeto speech maximizes the deployment of honorific and professional titles, minimizes the use of colloquial language, virtually eliminates many types of joking, underscores communicative decorum, and generally excludes personal topics. This formal environment, according to Garcia (1996), “impedes the development of an intimate relationship” (p. 150). In summary, the Code of Respeto implies distance in relationships. For closer relationships (i.e., with less power distance), the Spanish pronoun tú is used to convey friendship, informality, equal status and intimacy. In using tú, the Code of Confianza is activated. 27 Code of confianza. The Code of Confianza is active when both participants in a relationship refer to each other using the pronoun tú, enabling the creation and maintenance of friendship and family relationships. As the more informal address, the use of tú, says Covarrubias (2002), “minimizes the use of professional and honorific titles, includes the use of various types of nicknames, [and] facilitates the use of colloquial language” (p. 102). She explains that participants who use tú, and who therefore speak with confianza (hope, trust, familiarity, confidentiality), can self-disclose, ask for favors, criticize one another’s personal failings, express frankness, speak confidentially, and joke (p. 99). So while in vertical, high power distance relationships, only the higher status individual is able to express him or herself fully, openly, and more directly, in low power distance confianzapresent relationships, both individuals are potentially able to express themselves fully, openly, and more directly. This distinction may have implications for one’s conflict style, and points towards the mutability of one’s style to fit a particular conflict within a particular relationship dynamic. Additionally, the misinterpretation or misuse of the Code of Confianza and the Code of Respeto may even trigger a conflict. Conflict Trigger-Points Several definitions help provide the link between codes, misinterpretation, and conflict. Codes, as Philipsen (1992) notes, are socially constructed systems; Nadler, Nadler, and Broome (1985) define culture as a system of socially created and learned standards for perceiving and acting shared by members of an identity group. Therefore, codes are a reflection of the culture in which they are used. Returning to the basic assumptions of conflict mentioned in the introduction, Lindsley and Braithwaite (1996) 28 state that “conflict may occur based on different cultural perspectives of what constitutes communication competency. Vaahterikko-Mejia (2001) adds that conflicts are normally results of incompatibilities and misunderstandings, where one party has violated another’s normative expectations. Therefore, if two Spanish-speaking individuals from different cultures have different normative expectations for the uses of the Codes of Respeto and Confianza, or are even unaware of their existence, conflict may arise. Garcia (1996), Covarrubias (2002) and Condon (1988) all speak of the harsh effects that result from not acknowledging power distance. Condon says that to make light of a professional person’s title is to challenge his or her dignity. Garcia comments that a person who does not acknowledge class difference (i.e., by using tú instead of usted) will be perceived as “irrespetuoso” (one who lacks respect) (p. 146). And according to the majority of participants interviewed by Covarrubias (2002), the excessive or inappropriate use of tú is described as ser confianzudo (to be presumptuous or insolent) (p. 99). Garcia adds that misuse of the terms tú and usted can result in an unintentional verbal attack on another. Finally, Covarrubias says that perceived mismanagement of codes can even lead to social sanctions ranging from personal discomfort to, at least in abstract terms, the dismissal of a worker. As these reports suggest, misuse and misunderstanding of power distance can lead to serious consequences and may trigger, at the very least, tension and stressingredients inherent to conflict. The power distance script and its expectations vary quite markedly across Latin American countries as Hofstede’s (1991) research shows. But Albert (1996) says that the “knowledge of how power distance is enacted in various Latin American cultures in 29 different settings and in different roles is most important (italics original, p. 336). The literature by Garcia (1996), Covarrubias (2002), and Condon (1988) that I cite to explain respeto and confianza is based on Mexicans and none of the researchers extend their conclusions to include all Hispanic/Latinos. But, Fitch’s (1998) discussion of respeto, based on research of Colombians, draws similar conclusions. This thesis explores power distance variance in Colombia, Mexico, and Cuba and whether it is enacted through the Codes of Respeto and Confianza, or otherwise. It also explores whether power distance variance and expectations create conflict potential in inter-Hispanic/Latino relations. Literature Summary and Conclusions This literature review makes it clear that Hispanic/Latinos value relationships, value positive behaviors, and devalue negative behaviors in order to maintain harmonysometimes through avoidance behaviors. However, the literature provides evidence that for Hispanic/Latinos, relationships are not only important with each other, but to each other (i.e., power distance). This thesis explores whether context is a salient determinant to the Hispanic/Latino conflict dynamic. Power distance and its vehiclesthe Codes of Respeto and Confianza, provide a crucial context within which conflicts occur. Subsequently, they are highly influential as determinants for deciding (1) who might be involved in conflict with whom, (2) who might display aggression or react with avoidance, (3) who might use indirect or direct communication, (4) the range of emotional expressiveness allowed, (5) the instrumental boundaries of the given conflict, (6) where a conflict might occur and (7) how a conflict might be resolved and by whom. More over, the misuse, misunderstanding, and misinterpretation of these codes, or unconscious-conscious incompetence with these codes, may trigger conflict, or at 30 minimum, lead to tension and stress. By studying Colombian, Mexican, and Cuban conflict management and conflict resolution strategies, and the factors that trigger conflict with other Hispanic/Latinos, I will be able to further explore these ideas. 31