Microsoft Word - Heythrop College Publications

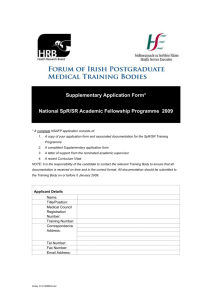

advertisement

TERESA OF AVILA Teresa of Avila (1515-1582) came from a well-to-do family of merchants. She entered the Carmelite monastery of the Incarnation in Avila (Spain) at the age of twenty. Twenty years later, she had a ‘second conversion’ – an experience of tears before a statue of the wounded Christ, which she likened to Augustine’s conversion in the Confessions – and this led her to plan a reform of the Carmelite Order, to return it to its early focus on contemplation. In 1562, she began a programme of reform with the founding of St. Joseph’s in Avila, which was followed by sixteen further foundations for nuns in the remaining twenty years of her life. She also set up a similar reform among the friars, with John of the Cross as one of her first recruits. She wrote prolifically during this time, a dangerous activity for a woman in Counter-Reformation Spain. She died in 1582, was canonized in 1622, and became a doctor of the RC Church in 1970. Her best known works are her Life, the Way of Perfection and the Interior Castle. Teresa has been studied in a variety of contexts in recent scholarship: as a mystic writing at the end of the great medieval flowering of mystical theology; as a religious reformer of the Catholic Reformation; as a feminine writer seeking authority against oppressive cultural and social forces; and as a theologian in her own right. It is now clear that Teresa was not the artless and theologically ignorant woman that she often said she was. While using homely images of watering the garden or spinning a cocoon, and mystical language of union, ecstasy and so on, rather than scholastic language, she developed ideas of God’s presence which contribute significantly to mystical theology. 2 First, she reflects, especially in the Interior Castle, on the difficult process of integrating the relationship with God with human activity and development. She seeks to bring God’s transcendence into the ‘centre’ of the person without removing its unlimited dynamism, thus giving the relationship between God’s transcendence and immanence a creative theological-anthropological treatment. Second, Teresa’s investigation of the ‘interior’ of the soul takes the theological and psychological journey into the soul, popular since Augustine, to new levels of detail, particularly in the examination of the state of mystical union. Union is mapped in way which allows for the discernment of different kinds and stages of union, with unusual acuity. Third, Teresa’s final position in the Interior Castle, that there is a union of contemplation and action, where prayer and virtuous work join together, though a common theme in late medieval mystical theology, is given a nicely constructed anthropological basis, showing how God-directed and world-directed activity can spring from a single ‘interior root’. Finally, Teresa’s reflections on the place of the Trinity and Christ in union bring her practical concerns into conversation with questions of unity and difference in God, particularly concerning the humanity of Christ. She finds ways of distinguishing interior and exterior functions of the self in the life of prayer without dividing them – again bringing transcendence and immanence together in her anthropology – by setting them within Christological and Trinitarian patterns of distinction and unity. Bibliography Rowan Williams, Teresa of Avila (London: Geoffrey Chapman, 1991; Continuum, 2004). 3 Edward Howells, John of the Cross and Teresa of Avila: Mystical Knowing and Selfhood (New York: Crossroad Publishing Co., 2002) Edward Howells