Sample Teaching Philosophy

advertisement

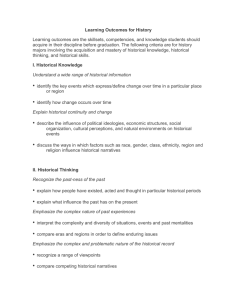

DEANNA D. FORSMAN 7933 Kimberly Lane N. Maple Grove, MN 55311–1787 deanna.forsman@nhcc.edu (763) 416–6722 Teaching Philosophy As an instructor, my primary goals are to teach students how to evaluate information and to communicate effectively through the written word. As an instructor of history, my goal is to help students understand how the events of the past have shaped the present. I have found that the best way to achieve these goals is by teaching the students to think as historians. I know that the majority of my students will not choose to be history majors. However, I believe that important functions of a liberal arts education are to develop critical thinking skills and the ability to appreciate multiple perspectives. With the vast array of information available over the internet, it is imperative that the modern citizen understand how to filter useful information from the unreliable. My basic approach to history courses is to demonstrate, and then have students practice, the rudimentary skills of the historian. One of the most basic skills is the ability to work with primary source documents. The first day of class, I give the students a primary source document, break them into small groups, and ask the groups to make observations based on the document. I stress in this first exercise that even if the students do not understand the context of the document, they can still obtain very useful information. For example, one of the documents I typically use describes a conflict between two neighboring city-states c. 2500 BC. Although the precise details of the conflict are difficult to follow, the students can easily recognize that the two city-states had measurements and concepts of boundaries, that they practiced irrigation, and that grain was important. Building upon this initial exercise, I emphasize that no written work is without bias, but by learning to recognize authorial intent, we can then determine how best to understand the information presented in the source. I assign primary sources from a wide variety of genres, ranging from poetry, scientific treatises, advertisements, epigraphy, narrative, literature, sacred texts, speech transcripts, law codes, and film. Some documents are useful for presenting an overview of historical events; others are better suited for explaining social or cultural developments. Particularly for pre-modern periods, I emphasize that our understanding is limited by the available evidence. To provide students with a more concrete example, I often will ask a class to imagine what future historians would think of the culture of contemporary America if the only sources to survive were Rap lyrics and Jehovah’s Witness pamphlets. I emphasize that each of these sources represents the attitudes and beliefs of a segment of contemporary Americans, even if such attitudes would not be considered mainstream by most. In addition to a strong emphasis on working with primary source documents, I introduce students to the concept of the historical argument. Although I expect students to learn content, it is not my primary focus. I want the students to understand that historians spend much of their time trying to understand the “how” and the “why” of the past and its relationship to the present. We develop interpretations based on evidence, and then argue about our interpretations. Rather than viewing history as something static and “knowable,” we view our understanding of the past as something mutable and ever-evolving. To introduce the students to this aspect of history, I encourage them to develop their own arguments. My primary requirement is that they remain faithful to the material presented within sources available in the course. I encourage them to disagree with my own interpretations, as long as they are fair to their evidence. I want my students to think for themselves. The emphasis on primary sources and historical argument is embedded within most of my assignments. Currently, I have several different learning activities, including in-class collaborative learning, short in-class quizzes, timeline assignments, short take-home essays, and midterm and final essay exams. The in-class collaborative learning and the take-home essays follow a very similar format. A typical assignment will ask students to work closely with one or two primary sources. I ask them to make observations based on the source and to use their observations to develop arguments and make connections with information presented in the course. For example, I ask my Western Civilization students to explain how Darwin’s theory of Sexual Selection reflects the values of 19 th century European Middle Class, and I ask my World Civilization students to explain why the ancient Chinese found Mahayana Buddhism more attractive than Theravada Buddhism. I have found that after answering these types of questions in a small-group setting, the students are much more confident of their ability to write a more formal take-home essay. These source-analysis activities also help prepare students for the essay exams. The data I have collected for Learner Deanna D. Forsman Outcome Assessment projects indicates that students perform better on the midterm when two of the three take-home essays are assigned before the midterm. I have developed a wide variety of methods to help students succeed. I encourage students to attend my office hours regularly by offering them extra-credit. They can come see me for help on the take-home essays, for guidance when studying for exams or quizzes, or just to talk further about something mentioned in class. Students are encouraged to send me drafts of their work before it is due, and I make suggestions for improvement. To prepare students for exams, I provide them with a study guide a week in advance. The students know that out of the eight questions on the study guide, four will appear on the exam, and they will be required to answer two. All students are strongly encouraged to pre-write answers before the exam. To provide additional incentive to the students, I offer them something I call the “Optional Online Study-Group.” Students who choose to participate outline an answer to one of the questions on the study guide, which they then email to me. Using D2L, I post these outlines anonymously with my comments and suggestions. Those students who participate then have access to all the posted outlines. I have also offered online review sessions using the chat tool, so that students can ask last minute questions. In order to engage students and help them to better understand events or mindsets of the past, I incorporate multimedia into my courses. For each class lecture, I develop a PowerPoint presentation incorporating two to five slides. Each slide includes a brief overview of the topic as well as maps or contemporary images. For example, to help students understand foreign influence in China between the 13th and 17th centuries, I show them images of Chinese porcelain decorated with Islamic and Persian motifs. I also incorporate music and film clips into my courses, whether it is Gregorian Chant performed by Benedictine monks to illustrate the other-worldly quality of the medieval Romanesque basilica, or Wagner’s “Flight of the Valkyries” to introduce a discussion of 19th century German nationalism. Students always enjoy the Monty Python clip that demonstrates why anyone who could afford to do so built a castle in the Middle Ages (as well as why most kings spent a great deal of time and effort demolishing their lords’ castles). I encourage all students to ask questions, both in and outside of class. The most engaging class periods developed when a student has asked a question related to a single point of the lecture, such as the status of women in Classical Greece, which sparked discussion from the entire class, through which the students gained a better understanding of Ancient Greek culture. The more interactive classes are always accompanied by a higher energy level, and I enjoy responding thoughtfully and informatively to student questions. On those occasions when I do not know the answer to a particular question, I will tell the students that I do not know the answer, but then offer my best guess. I emphasize that my answer is based on what I do know, thus modeling for the students the process of developing a historical argument from limited evidence. It is perhaps a truism that instructors teach more than content. Although it is unrelated to the specific goals of history, I emphasize that the choices students make in the classroom have larger implications. Some students are living on their own for the first time, and have not ever been expected to be responsible for themselves or their choices. I structure my classes to reward students who take responsibility for themselves and penalize those who do not. For example, all assignment due dates and exam dates are very firm, and I will not grant extensions or make-up exams for any reason, unless the student has contacted me in advance. Whenever possible, I emphasize the other applications of skills taught in my classes, whether it is critical thinking, the ability to communicate ideas clearly, or the ability to meet a deadline. It is my hope that my students will acquire the desire to become life-long learners in addition to gaining valuable skills that they can employ in other college courses, as well as any endeavor they choose to undertake. 2