Honey dip child study

advertisement

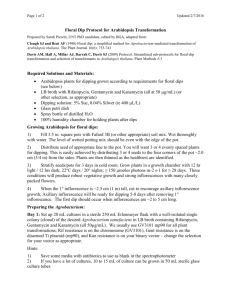

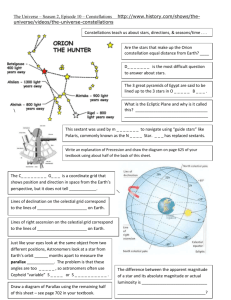

Electronic Supplementary Material (Whiten et al.) 2. ‘Honey dip’ Child Study Method Participants Twelve 3- and 4-year-old children (range 36-55 months), four boys and eight girls (Table 1, main paper), were recruited from a nursery school in Central Scotland. Materials Participants were presented with the ‘honey-dip’ box used by Marshall-Pescini and Whiten (2008), modified for use with children (see techniques below), together with a tool which could be used to perform either a ‘dipping’ technique or a more complex ‘probe-and-lever’ technique yielding more rewards (Fig. 6). The box was 9 x 6 x 6 cm in size, was completely opaque, and was fixed to a wooden table at a height suitable for young children to work on it. Techniques applied Participants witnessed two techniques applied to the box, simulating those used in the Marshall-Pescini and Whiten study. a) Dipping-technique. In the chimpanzee study this involved dipping a stick-tool into honey inside the box. This was not hygienic for child subjects. Instead, the box was filled with numerous coloured metallic stars and bracelet beads. To demonstrate dipping for stars, echoing honey-dipping for the chimpanzees, the adult model used the index finger of her left hand to slide open a small trapdoor (1 cm square) on top of the box. Whilst holding this trap door open, the model used her right hand to insert a magnetic stick-tool into the hole. Some stars would stick to this, so the tool could be withdrawn and the stars easily pulled off it. The beads could not be removed in this way because they were not metallic. b) Probe-and-lever-technique. In the chimpanzee study, this involved inserting the stick-tool into a hole on the side of the box, thus pushing in a rod holding the box lid down. The stick could then be inserted in the top hole and the whole lid levered open so that the entire contents of honey and nuts could be obtained. Pilot work confirmed this was too easy for 3-4 year-old children to discover by themselves, so an additional, spring-loaded sliding panel was added, covering the hole on the side of the box (Fig. 6). In the present study, the model used the index finger of her left hand in order to slide open the sprung panel on the side of the box. Whilst holding this open, the model pushed the stick-tool into the hole thus revealed. This pushed in a small bolt that was holding the lid of the box closed. After having poked the bolt, the model released the sprung panel, allowing it to cover the bolt once more. The model then employed a variation of the dipping technique, opening the trap door, inserting the tool, and using it as a lever to open the hinged lid, making all of the box contents available. The incorporation of the dipping technique variation into this procedure, meant that the latter was built cumulatively on the already mastered dipping technique. As in the chimpanzee study this more complex technique allowed all the contents of the box to be obtained, including larger bracelet charms evidently highly attractive to the children. The dipping technique did not allow the participants to obtain these larger non-metallic rewards. Many insertions were required to obtain all the stars. In contrast the probing technique allowed rapid access to all the stars and charms. Procedure The procedure began with a no-model baseline phase, followed by two experimental phases. These involved first the dipping technique, and then if this was mastered by the child, a second phase in which the probe-and-lever technique was modeled. Baseline phase In the baseline phase each participant was allowed to explore the box individually. Upon entering the testing room participants were seated in front of the box and asked ‘What do you think you do with this?’ The child was then allowed to interact with the box for two minutes, or earlier if they indicated they did not wish to continue. One participant discovered the dipping technique individually in this phase, and was accordingly progressed to Experimental phase 2, described further below. Experimental phase 1: The dipping technique This experimental phase began on completion of the baseline phase. The experimenter sat to one side of the child and presented four consecutive task demonstrations of the dipping technique, removing the stars from the tool after each withdrawal. After four task demonstrations the experimenter said ‘Now it’s your turn’ Each child was allowed up to three dips. The number of stars retrieved was counted and traded for an equal number of child-friendly small beads that the children could place on a bracelet string. Experimental phase 2: The probing technique Upon completion of the dipping phase, which was successfully achieved by all participants, they were exposed to four consecutive demonstrations of the probe-andlever technique. The experimenter again said ‘Now it’s your turn’ If the child was successful in opening the box they were allowed to choose one large bracelet charm to place on their bracelet string. Statistical Analyses As noted above, all children successfully dipped in Phase 1. There was thus significant evidence for social learning in this phase, since only one child was successful in the baseline phase (McNemar Test, p < 0.006). In Phase 2, eight children successfully mastered the more complex technique, three completed part of it by pushing back the sliding panel but failed to insert the stick-tool to push the bolt (Table 1) and just one child persisted in using only the dipping technique, as all chimpanzees had done in the earlier study. Significantly more of the children thus showed evidence of cumulative social learning than had the chimpanzees (Fisher Test, p < 0.03).