Campaign Assessment: Measuring Progress in the Air

advertisement

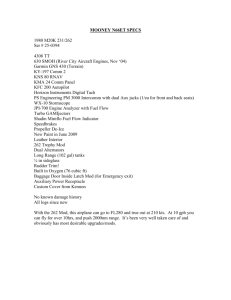

© British Crown Copyright 2005/MOD Campaign Assessment: Measuring Progress in Air Operations Paul Stoddart, Scientific Adviser Operations, Air Warfare Centre Ladies and Gentlemen, It is a privilege to offer this presentation as part of ISMOR22. My name is Paul Stoddart. I work for the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory, an agency of the United Kingdom Ministry of Defence. In the eighties, I had the honour of serving in the Royal Air Force as an engineer officer. Since late 2001, I have worked in Operational Analysis at the Royal Air Force Air Warfare Centre. This has included an unexpected 10-week holiday in Saudi Arabia in early 2003. Some of my observations arise from that experience. The declared title of my presentation is ‘Measuring Progress in Air Operations’. A rather neater title might be ‘Measuring the E in EBO’. Effects Based Operations require us to look beyond kinetic actions and attritional results to using a variety of methods to achieve a range of outcomes. We have to consider the immediate and the longer-term effects, the local and the wide ranging and the beneficial and the detrimental. The focus must be on results and consequences not on effort and action. An effect implies a measure and measurement of effect is essential in modern operations. I believe that unless we can measure the effects we seek to achieve then we will not master Effects Based Operations in the full sense of the term. I offer a possibly apt quotation, for once not from Clausewitz or Sun Tsu but from the world of science, from Lord Kelvin who gave his name to the scale of absolute temperature. Kelvin stated, I am paraphrasing somewhat as he had a rather verbose Victorian style, that we only fully understand something when we can measure it. As for measuring progress in air operations, the short answer is that this is very difficult. Even a cursory review of air operations and campaigns of the last 100 years shows that achieving an accurate and timely measure of the effectiveness of our actions is extremely challenging. For that reason, it has often been done badly. Today, we are still struggling to do it even reasonably well. Indeed, I would suggest that our current limited ability to measure effects and progress, quickly and reliably, represents a significant capability gap and one that is as important perhaps as the absence of a particular platform or system from our order of battle. It is a gap that must be corrected or at least minimised as our numbers of platforms and other systems tend to reduce. We cannot always rely on having a superfluity of resource and thereby winning through sheer weight of effort. Leaving aside lengthy definitions of EBO, a measure of effectiveness should help answer the commander’s questions: “How well are we doing?” Analysis is at the core of the EB approach. We must ensure that analysis can answer the questions that arise in operations and answer them at the time rather than in retrospect. This requires analysis to be in step with action. This requires the decision-makers to understand effects and the measurement of effect as thoroughly as they understand our own weapon systems. I will concentrate on phase 3 of Air operations, that is, warfighting. I do not suggest that it is worthier of study than the other phases or the other domains but it is particularly challenging. In recent years, Phase 3 of air operations have been short and intensive. Much data can appear in a short time or there can be a shortage of data. Sorting the wheat from the chaff is always a problem and working out ‘how well are we doing’ is not easy. We could take the view that this does not matter very much. After all, we always win and we generally win quickly. The Gulf War of 1991 was won in around 40 days with Air shaping the battlespace for the 100-hour Land operation. Air operations in Bosnia lasted only 12 days. Phase 3 of the Gulf War of 2003 was even faster than its predecessor was at only 28 days. Kosovo was the aberration. It was still short by 20th Century standards at 78 days but the failure to adopt a rigorous Effects Based approach from the start caused it to be far more protracted than originally envisaged. Despite our recent ‘quick wins’, I contend that we must improve our ability to understand effects and to devise measures for them. A better understanding of effects should enable us to win more quickly, with lower risk, with lower use of resources and ideally with lower collateral damage. D:\106741266.doc 1 of 4 © British Crown Copyright 2005/MOD The great majority of what I have read on EBO was at the doctrinal level. Certainly, doctrine development is essential but it must be balanced with the compilation of operational and tactical level examples. It is not enough to declare that we will follow an EB approach but to offer little or no guidance as to how to identify the effects required and how to achieve them and then measure them. Doctrine is the foundation but examples of EBO from the real world are essential for consolidation of the message. We learn from doctrine but full understanding comes with example and experience. Ideally we will learn from the experience of our predecessors so that we will avoid repeating mistakes and instead apply good practice from the start. Apart from doctrinal level study, most effort appears to have been aimed at how the EBO results might be compiled and then presented to the commander. Various schemes exist including traffic lights with colours denoting levels of achievement and flow charts showing progress as a bar advancing across a scale and changing colour as it goes. Three-dimensional graphs look rather imposing and may offer a neat summary of results. Such schemes are fine as a precis of achievement but how do we get the information with which to populate them? On that vital issue, there is far less guidance available and that is a critical omission. We cannot achieve EBO simply through declaring the benefits of such an approach and by producing the Powerpoint tools for presenting the results. The Coalition undoubtedly had Powerpoint supremacy during the last Gulf War but that did not help actually measure the effects. The difficulty of measuring effects can result in 2 responses. Either we make little effort to do so or we measure that which can be readily measured. We must beware this all too tempting latter option. We should bear in mind Robert McNamara’s directive that we must make the important measurable, not the measurable important. The Air domain has proved to be very prone to measuring effort expended or the immediate results of its actions rather than the effects achieved – or in some cases, not achieved. Effort and the expenditure of resources is easily measured: sorties flown, tons of bombs delivered and (the air domain’s favourite) bridges dropped. Measuring effects is more challenging. It is almost always a rather slow process and there is potential for it to get disconnected from actions. This action-analysis disconnection arises all too easily in the real world. The following view of the modern Air operation cycle is a variation of the OODA loop: Observe. Orient. Decide, Act. The cycle runs from Assess the situation to Decide on the course of action, Prepare the actions and then Execute. The results are Assessed and the process is repeated until we see a white flag or whatever other success indicator we are waiting for. The cycle divides between the cognitive domain of Assess and Decide and the practical domain of Prepare and Execute. This is reasonable enough but unfortunately in practice rather than one loop running iteratively through its stages in sequence we get 2 loops running concurrently and more or less separately. In addition to separation the 2 loops run at different speeds. Building and executing an air tasking order is well developed and runs relatively smoothly and quickly. Unfortunately, the cognitive loop is not nearly so well understood, resourced or practiced. As a result, the ATOs are built and flown with insufficient guidance from the analysts. We aim to get inside the adversary’s OODA loop by acting faster than he can respond. The adversary cannot assess or respond to what has happened before the next event occurs. Paradoxically, we are now inside our own OODA loop. Events, the events that we are driving, are occurring faster than we can assess them. This state of affairs actually offers a rather unusual option for an Air operation; that we might deliberately slow down our approach, slow down our operational cycle and actions, so that the analysis task can keep up. This would only be acceptable where Air was the supported, preferably the only, domain involved. Where Air was supporting another domain we would have to maintain a rate of action in line with our customer. An operation such as Operation ALLIED FORCE over Kosovo might allow for an operational pause. In Operation IRAQI FREEDOM, Air did not have such an option as Land was making such rapid progress. The result of this separation in the operational loop is that, according to an eminent assessor of the Air domain: ‘Airmen have become driven by process not strategy’. In the absence of timely analysis, we continue to kill the enemy and to break his stuff. In the absence of guidance, we tend to overkill targets in the hope of ensuring the effect. The result is wasted effort, possibly higher collateral damage and perhaps a more protracted conflict. D:\106741266.doc 2 of 4 © British Crown Copyright 2005/MOD Measurement of effect can be attempted through a bottom-up approach of assessing each action. This is based on the familiar Strategy to Task process with a clear link from each action back up to the strategic objective. So forming an audit trail. In Operation IRAQI FREEDOM, extensive effort was invested in devising a means to assess the air plan. The overall intent was progressively sub-divided into x operational objectives, y tactical objectives and z tactical tasks and finally actions. The number of elements increased by a factor of 3 or 4 times at each level down. This strategy to task approach is useful but it is not ideal for assessing effects and progress. The analysis comprised assessing the result of each element, factoring it by an appropriate weighting to get a score and then aggregating all the scores at one level to produce a result for the ‘parent’ element at the next level up. In theory it made sense but in practice it proved impossible to get sufficient data and to analyse it fast enough. It ran far slower than the practical side of the operational loop and offered limited guidance. I am not suggesting that we should stop measuring our actions but we also have to look at the bigger picture as a means of measuring progress. A complementary approach is to examine directly the output of the target system. Air Warfare Centre tried this for an integrated air defence system. The system was broken down into its elements and each element was assigned a weighting to represent the importance of its contribution to the whole. The weighted scores of element performance were progressively summed to give an overall score for the entire system. One single such score at any particular time was not particularly informative. Its worth was that it allowed the changes in the system to be monitored over time – we had a measure of that system’s performance changing, which offered some indication of the effect we were achieving. Of course, this system level approach is not infallible but it has the merit of forcing us to monitor the adversary system itself. The challenge is gathering and analysing sufficient data to understand the system in a timely manner. We must study our potential adversaries and his systems in depth and detail. This includes the tangible systems such as integrated air defence, communications networks and power generation and distribution. It must also include the intangibles such as political and military influence networks and socio-cultural elements. These intangibles of the cognitive and social domains are a particular challenge and military analysts must look outside their traditional areas to the world of softer sciences. In short, we must know and understand more than the adversary’s order of battle. We must understand how all his systems fit together and work together. We must know his ORBAT and his order of systems, his ORSYS. And we must be able to measure the output of those systems. However, it will not always be possible to understand an adversary system to any great extent. We must develop methods for defining and bounding for an action or series of actions what might be termed the outcome spectrum. Even if we do not know not fully how a system works, we should be able to derive a range of plausible system outcomes to our actions: the most likely outcome, the best case, the worst case plus the likely duration of effect and any implications. Such knowledge will help inform the decision making process for the next stage of the operation. That leaves the issue of research and education. We have knowledge in depth of platforms, weapons and their associated enabling systems. Do we have such strength in depth of the EB approach? I would suggest that we do not. The attritional approach could function with knowledge of weapons and their immediate effects. The EB approach requires that weapon knowledge plus an understanding of which effects air power can achieve, how it can best achieve them and how they can be best measured. To address this issue, we must learn from history. We should assess past Air operations from an Effects Based perspective. Even where they were not explicitly planned on an EB basis, the commanders were still seeking effects of some sort. We need to identify the effects sought, the actions taken, the measures of effectiveness employed (if indeed any were) and the actual effectiveness of those actions. From that, we should be able to identify whether the effects sought were the right ones and how successful the actions and measures of effectiveness actually were. D:\106741266.doc 3 of 4 © British Crown Copyright 2005/MOD These findings would be databased for the guidance of planning staff, analysts and commanders in future air operations. Rather than starting from scratch, we would have some guidance as to how certain effects can be achieved. The database would also form the basis of educating airmen in the EB approach to the application of air power. There must be widespread understanding of the means, capability and limitations of air power in achieving effects. A balance between action and analysis is essential for EBO. We must balance our capability to take actions with the capability to collect and analyse the data required to measure them. We must analyse the target systems we are likely to face and determine how they work, how we can measure them and how we might achieve effects against them. We must also identify the outcome spectrum of likely actions against target systems: the most likely and the best and worst cases. We must balance the doctrinal level of EBO with historical analysis of the operational and tactical levels so as to learn from the experience of our predecessors. We must balance the education of airmen in our platforms and systems with knowledge and understanding of the actions, effects and measures of effectiveness from past campaigns; those that worked and why they worked and those that did not. It has been said that good judgment comes from experience but that much experience comes from bad judgment. We must learn from history. It will take more than good intentions, doctrinal study and Powerpoint to achieve the EB approach. The basis will be target system study, historical analysis and education. Wars are not won by process, they are won by decision and action. And knowledge is the basis of decision. And analysis is the basis of knowledge. Thank you for your attention. © British Crown Copyright 2005/MOD Published with the permission of the Controller of Her Britannic Majesty's Stationery Office. D:\106741266.doc 4 of 4