This report - Equality and Human Rights Commission

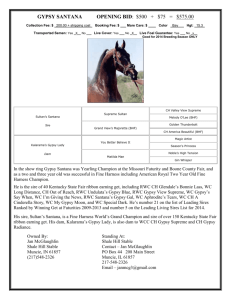

advertisement