RANGITANE O TAMAKI-NUI-A-RUA SUMMARY OF GENESIS

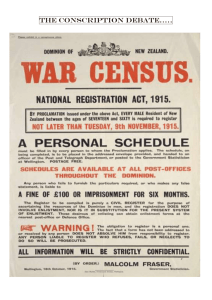

advertisement

RANGITANE O TAMAKI-NUI-A-RUA SUMMARY OF GENESIS ENERGY CASTLEHILL WINDFARM CULTURAL VALUES ASSESSMENT. 1. Introduction. My name is Patrick Parsons and I live at Poraiti, west of Napier. I have a long background in Maori history and custom and finished a career as a secondary school teacher in 1990 to focus on Waitangi Tribunal claims in my area. In the Hawke’s Bay region I specialise in traditional Maori history and genealogy. I am author of the histories In the Shadow of Te Waka and Waipukurau-the History of a Country Town and co-author of West to the Annie. 2. I have previously been commissioned by Rangitane o Tamaki-Nui-aRua to prepare a cultural values assessment for the Contact Energy Waitahora Windfarm project. Castlehill is located to the south-east of the Puketoi Range about 30 kilometres east of Pahiatua. It is a remote area with an elevated and rugged terrain and much of the access is along valley floors. 3. This Cultural Values assessment investigates the relationship between Rangitane and the landscape along a corridor extending from the coast at Mataikona, through the Castlehill windfarm zone and on to the Tararua Ranges west of Pahiatua. It explores the ancestral links between Rangitane and the land beginning with the Kupe people and extending to the era of Government alienations (1853-1875). 4. Sections 1 and 2 of this report address the rationale and methodology used to gather the material for the assessment. In terms of preservation of customary history it was found that early Government purchases equated to loss of identity with the land and a corresponding loss of history. The establishment of the Maori Land Court in 1866 provided the Maori with a vehicle to tell their history and have it recorded in the minute books. Until Maori became familiar with the system, the evidence gathered was rather sparse. By the 1880s Maori were more forthright, titles were more contested and history was recorded in more detail. 5. Sections 3-6 and 8 relate to Government purchases and surviving documentation concerning each of them. In some cases survey maps survive which provide boundary names in Maori. The purchase deeds identify Maori who were present at their signing and who presumably had ancestral and occupational rights to the land. This was not always the case as visiting Maori of rank were often invited to sign the deeds as a courtesy or as witnesses. Purchase details such as recorded in Turton’s Deeds don’t include information on customary rights. Purchase commissioners were not required to identify tribal affiliations as part of the purchase protocol. Negotiations were conducted with principal chiefs and it would have required specialist genealogical knowledge to identify each by tribe. 6. Section 7 of the report, titled Alfredton: the School and the People provided a surprisingly comprehensive study of Maori occupation in the area known as the Moroa clearing. This area follows the river tributaries of the Waitawhiti, Te Hoe, Ihuraua and Tiraumea flowing west from Castlehill, then north to the Manawatu. Large sections of the valley floor were clear of forest. It is likely they weren’t all natural clearings and that generations of seasonal occupants had burnt parts for cultivations and kainga. Archaeological sites including fortifications, cultivations and urupa all add to the knowledge of bygone times. 7. Section 9 of the report concerns the writings of the Anglican missionary William Colenso who passed through the seventy mile bush in March 1846. Not only does he leave a description of the primaeval forest but he visits the settlements of Te Hawera and Ngaawapurua. It was at Te Hawera that he met the aged chief Karepa Te Hiaro who became a staunch convert to the new faith. Shortly before his death in December 1849 Te Hiaro called his people together and exhorted them to cleave to the new faith. 8. Section 10 of the report contains extracts from the addresses of Norman Elder, botanist and tramper who taught at Hereworth School, Havelock North and belonged to the H.B. Historical Society. He discusses vegetation, weather hazards and the best routes across the Tararua ranges for early Maori. 9. Section 11 makes the case for Rangitane occupation of Puketoi No. 4 rather than the list of sellers identified by the Makuri purchase. The Crown-grantees of Puketoi No 4 all identify with one or other of the descent lines of Rangitane, and principally with Rangitane of the Manawatu river. 10. Section 12 examines in greater detail Maori occupation of the valley floors and rivers of the Moroa clearing. The justification for this is that it is one of the few records of how Maori lived and utilised the resources of the land and conveys a sense of seasonal relationship to a remote and sparsely-settled territory. It provided fishing and fowling grounds, shelter, cultivations and timber for dwellings, fencing and canoes. Birdlife, some of it now extinct was plentiful until the late 1800s and Maori continued to exercise customary rights even after alienation of the land. 11. Section 13 of the assessment considers wahi tapu or places of spiritual significance to the Maori. It makes the case that alienation of title to the land has a devastating impact on the places and events that were important to earlier generations. Memory of these places and their significance is dependant on generational access to them and the retelling of the story. When regular habitation ceases the knowledge of past deeds soon fades, in much the same way that European colonists to this land lost contact with their places of spiritual significance. 12. A genealogy is provided at Section 14 for the chief Te Kawe who was killed along the riverways of Moroa. Was this the same chief who W.J. Saunders learned was buried near the Waipori stream? It is rather a tenuous link but it serves to illustrate how associations with the land vanish if not preserved. 13. The interview with Hanatia Palmer at Section 15 demonstrates the knowledge that remains with people of long association with the land. They are a valuable resource and are sometimes the sole repository of key elements of tribal history. Locating these people and taking the time to listen to them is not always a priority and their value is often only recognised when they have gone. 14. The summary of the above research appears at Section 16. The historian who sets out to identify and record what is left of the story of tribes like Rangitane always comes away with unanswered questions. Have I represented the ancestors of this land fairly? Is there more material out there that I have missed? Have I provided enough for young Rangitane to grasp hold of and regain a sense of belonging? 15. Sections 18-20 concern consultation with Rangitane, contemporary cultural values and issues and recommendations. Questions concerning this section will be addressed by Rangitane.