Original: English

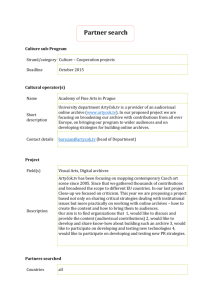

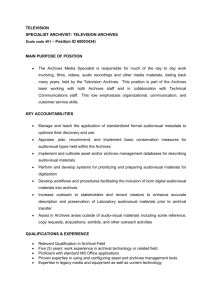

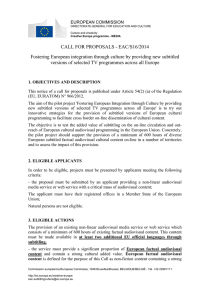

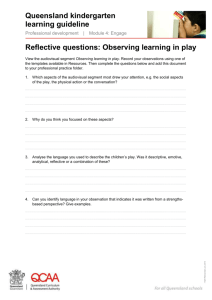

advertisement