NEW ENGLAND LAW REVIEW

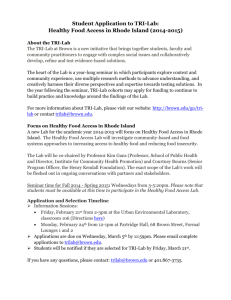

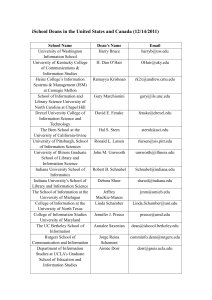

advertisement