Caesarean section for all patients

advertisement

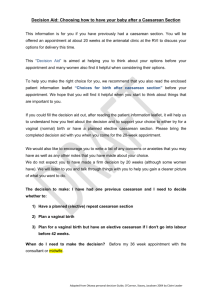

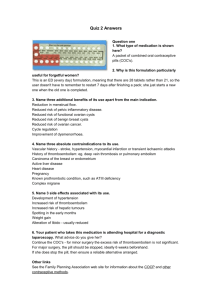

106738426 Caesarean Section for All Patients? N. Fisk Institute of Reproductive and Developmental Biology, Imperial College, Hammersmith Hospital Campus & Centre for Fetal Care, Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital, London, United Kingdom Caesarean section rates over recent decades have widely been condemned as being too high. Certainly their doubling over the last 20 years followed, rather than mediated, sharp declines in maternal and perinatal mortality. Their huge variation in the developed world (6-38%) cannot be explained on obstetric grounds, and numerous analyses have shown that the chief determinants of two- to three-fold differences within countries are the woman's insurance, her choice of obstetrician, and socio-economic status. It thus became obstetric dogma that all obstetricians should strive to achieve vaginal delivery, and prevent unnecessary caesareans. But what is the ideal rate? Figures ranging from 9-15% have been proposed but based on scant evidence. In direct contrast to the above, one third of female obstetricians in a survey in the mid-1990’s indicated that they would choose to be delivered always by elective caesarean section, in the absence of any medical indication.1 Their views were presumably influenced by the safety of modern elective caesarean section under epidural anaesthesia, thrombo-prophylactic and antibiotic cover, which is now arguably as safe as an attempt at vaginal delivery. Most wished to prevent long-term damage to their pelvic floor, and 39% in addition wanted to prevent damage to their baby. So what are the arguments? More recently the same question was posed to US obstetricians, 46% of whom wanted a non indicated caesarean section.2 Vaginal delivery is the major aetiological factor for stress incontinence, prolapse and anal incontinence in women. Recent functional and structural studies of the pelvic floor indicate that many women, even the majority, damage their pelvic floor as a direct result of vaginal delivery, and around one third develop symptoms of incontinence, especially after assisted vaginal delivery. Around 40% of women have long-term incontinence of urine, flatus or stool,3 and it has been estimated, that in the USA women have a lifetime risk of 11% needing an operation for prolapse or incontinence.4 It is not possible to predict accurately which women will require assisted delivery, and which women will suffer these complications. The chief risk factor thus appears primiparity, and pre-emptive caesarean section a not illogical preventative strategy. 106738426 Allowing women to labour vaginally is also associated with not inconsequential fetal risks, including intrapartum death (ca.1 in 1700),5 intrapartum acquired hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy (1 in 1750),6 intrapartum acquired cerebral palsy (1 in 4000),7 and the greatest risk, stillbirth at term prior to labour (1 in 550).8 Although these figures may be adjusted up or down depending on the various data sources, cumulatively the fetal risks of vaginal delivery exceed 1 in 500. In contrast, the average woman would request elective caesarean section at a much lower risk of 1 in 4000.9 A recent national survey in the UK indicated that 92% of women wanted to be delivered by the route that was safest for the baby: the same survey showed that 54% of obstetricians thought that was by caesarean section.10 If obstetricians increasingly regard abdominal delivery as preferable, at least for themselves, how should they respond to the low risk woman who asks for a caesarean section? Editorials in the 1980’s argued that such requests should be denied.11,12 We let women choose freely their method of contraception, whether to avail themselves of prenatal diagnosis and termination of pregnancy, their pregnancy care provider and setting, their analgesia and birth position, and whether or not to breastfeed, yet some argue that refusing such requests is not paternalism.13 Indeed the Ethics Committee of FIGO, our international body, deemed in 1999 that caesarean section for medical reasons was not ethically justified. In contrast, surveys now show that a clear majority of obstetricians would acquiesce to informed requests.10,14 Should all women be offered an elective caesarean section? Clearly this is not currently appropriate or achievable for all patients. Further, there are risks to caesarean section, especially the small but important risk of abnormallypositioned or adherent placentation with recurrent abdominal delivery.15 Even this, however, needs to be offset against the avoidance of pelvic surgery in later life. Then there is the increased relative risk of respiratory distress with prelabour caesarean at 38/9 weeks,16 although this is usually treatable with good outcome, unlike unexplained intrauterine death at or after the same gestational age.8 To inform this debate, there is urgent need for good research data on the relative long-term outcomes of vaginal versus elective caesarean delivery. Patient choice is having its greatest effect where there is an increased chance of intrapartum emergency caesarean section, such as in primigravida needing induction, in the elderly primigravida, and in the presence of twins or a prior caesarean section, and the women is planning only two children. It is now clear from the Term Breech Trial that elective caesarean section is safest for breech 106738426 deliveries.17 Although many obstetricians had considered vaginal breech delivery safe, this multicentre international randomised controlled trial showed that only seven caesareans were required in low perinatal mortality countries to prevent one serious adverse neonatal outcome.17 Similar trials of elective abdominal versus vaginal delivery are now planned for twins, and those with a single previous caesarean section, but is it not now time for a “term cephalic trial”? There are further reasons why the CS rate is destined to rise further. Firstly, women in the developed world are reproducing later in life, and rising age correlates linearly with section rates18,19 Next, babies are getting bigger, as are their mothers.20 Indeed, anthropologically man is the only mammal in which the fetal head almost entirely occupies the maternal pelvis, and has and is evolving away from a reliance on vaginal birth.21 Finally, the litigation costs resulting from vaginal delivery continue to rise exponentially, with annual premiums in some jurisdictions exceeding half a million dollars per obstetrician, and settlements encroaching on 8 figures. One wonders how much longer society, and particular health care providers, will continue to be able to afford vaginal delivery. Patient choice is assuming greater importance in maternity care, and in this light efforts to reduce the caesarean section rate further seem doomed. Medical opinion on this issue is changing with recent editorials arguing that a further rise in rates is not only to be expected, but may be desirable.22, 23 The assumption that caesarean section rates are too high is no longer tenable, and reducing rates may be counter to maternal and fetal interests. Caesarean rates in the twenty first century will be driven up by consumer demand,24 and will almost certainly exceed 50%. References 1. AL MUFTI R, MCCARTHY A, FISK NM. Obstetricians' personal choice and mode of delivery. Lancet 1996;347:544. 2. GABBE S, HOLZMAN G. Obstetricians' choice of delivery. Lancet 357:722, 2001 3. MACLENNAN AH, TAYLOR AW, WILSON DH, WILSON D. The prevalence of pelvic floor disorders and their relationship to gender, age, parity and mode of delivery. Bjog 107:1460-70, 2000. 4. OLSEN AL, SMITH VJ, BERGSTROM JO, COLLING JC, CLARK AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 89:501-6, 1997. 106738426 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. CONFIDENTIAL ENQUIRY INTO STILLBIRTHS AND DEATHS. 8th Annual Report. London: Maternal and Child Health Research Consortium, 2001. ADAMSON SJ, ALESSANDRI LM, BADAWI N, BURTON PR, PEMBERTON PJ, STANLEY F. Predictors of neonatal encephalopathy in full-term infants. Bmj 311:598-602, 1995. MACLENNAN A. A template for defining a causal relation between acute intrapartum events and cerebral palsy: international consensus statement Bmj 319:1054-9, 1999. COTZIAS CS, PATERSON BROWN S, FISK NM. Prospective risk of unexplained stillbirth in singleton pregnancies at term: population based analysis. Bmj 319:287-288, 1993. THORNTON J, LILFORD R. The caesarean section decision: patients' choices are not determined by immediate emotional reactions. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 9:283-88, 1989. THOMAS J, PARANJOTHY S. RCOG Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit. The National Sentinel Caesarean Section Audit Report. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists., 2001. HALL MH. When a woman asks for a caesarean section. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 294:201-2, 1987 JOHNSON SR, ELKINS TE, STRONG C, PHELAN JP. Obstetric decisionmaking: responses to patients who request cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 67:847-50, 1986 HARRIS LH. Counselling women about choice. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 15:93-107, 2001. COTZIAS CS, PATERSON-BROWN S, FISK NM. Obstetricians say yes to maternal request for elective caesarean section: a survey of current opinion. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 97:15-6, 2001. ANANTH CV, SMULIAN JC, VINTZILEOS AM. The association of placenta previa with history of cesarean delivery and abortion: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 177:1071-8, 1997. MORRISON JJ, RENNIE JM, MILTON PJ. Neonatal respiratory morbidity and mode of delivery at term: influence of timing of elective caesarean section. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 102:101-6, 1995. HANNAH ME, HANNAH WJ, HEWSON SA, HODNETT ED, SAIGAL S, WILLAN AR. Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet 356:1375-83, 2000. 106738426 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. ROSENTHAL AN, PATERSON-BROWN S. Is there an incremental rise in the risk of obstetric intervention with increasing maternal age? Br J Obstet Gynaecol 105:1064-9, 1998. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. NHS Maternity Statistics England 1998-99 to 2000-01. London: DOH Bulletin 2002/11, 2002. BROST BC, GOLDENBERG RL, MERCER BM, et al. The Preterm Prediction Study: association of cesarean delivery with increases in maternal weight and body mass index. Am J Obstet Gynecol 177:333-7 1997. STEER P. Caesarean section: an evolving procedure? Br J Obstet Gynaecol 105:1052-5, 1998. DRIFE J. Maternity services: the Audit Commission reports. Bmj 314:844, 1997. EDITORIAL. What is the right number of caesarean sections? Lancet 349:815, 1997. PATERSON BROWN S, FISK NM. Caesarean section: every woman's right to choose? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 1997;9:351-5, 1997.