THE COMPETITIVENESS OF REGIONS AND LOCALITIES IN

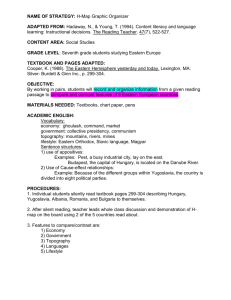

advertisement