The management of cardiac arrest

advertisement

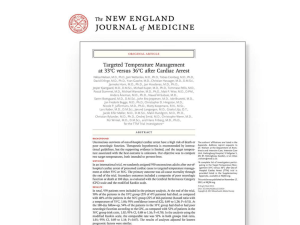

THE MANAGEMENT OF CARDIAC ARREST The management of cardiac arrest INTRODUCTION Cardiac arrest has occurred when there are no palpable central pulses. Before any specific therapy is started effective basic life support must be established. Three cardiac arrest rhythms will be covered: 1. 2. 3. Asystole Ventricular fibrillation Pulseless electrical activity (PEA) PRE-HOSPITAL CONSIDERATIONS Cardiac arrest in a child has a dismal prognosis. Every effort should therefore be made to prevent it occurring by early recognition of potentially serious illness and appropriate management. Occasionally it is, however, inevitable. It is particularly difficult to manage in the pre-hospital setting because ideally a team of skilled, well equipped people are required to provide optimum simultaneous management of the airway, breathing, circulation (cardiac massage) and drug administration. This abundance of resources is seldom, if ever, available outside hospital and therefore the recommended guidelines and protocols may not be possible to implement in full. It must be remembered that, at the present time, the only factor known to improve the outcome of paediatric arrest is the time from the arrest to the arrival at hospital. This is regardless of the skill of the personnel or interventions performed. Thus the single most important “treatment”, likely to improve the child’s chances of survival, is not to delay in transferring the child to hospital. It is possible that if this is done, then other appropriate procedures may also help the child’s outcome. So when to move? This will depend on a number of issues, ranging from the size of the child to equipment available. Points to bear in mind are: . . 53 (Updated January 2010) THE MANAGEMENT OF CARDIAC ARREST If the child is small enough, remember, if possible, to “scoop and run” into the ambulance, rather than wasting time bringing equipment to the scene. As in all resuscitation, airway and breathing come before circulation and drugs. Good basic life support is essential and should not be sacrificed at the expense of performing advanced interventions such as intraosseous cannulation and drug administration. However, some advanced interventions may improve the quality of the basic life support. A laryngeal mask airway of an appropriate size may be inserted to facilitate ventilation during long transportation times. Endotracheal intubation should only be undertaken in exceptional circumstances. For example, such as in protecting the airway in children at high risk of aspiration in near drowning. If the child is in ventricular fibrillation, the most urgent treatment is defibrillation, and this should not be delayed. As for an adult, the sooner the child is defibrillated, the more likely the return to a rhythm with an output. It may be appropriate to perform one cycle of basic life support before moving the child as a primed myocardium has been shown to respond better to energy —particularly if the arrest is thought to be due to hypoxia, as oxygenation is also crucial. The remainder of this section deals with what is considered to be the optimum management of asystole and PEA (non-shockable rhythms) (Figure 3.4) and ventricular fibrillation (VF) and ventricular tachycardia (VT) without an output with full facilities available (see Figures 3.5). It is, however, important to appreciate that it will not always be possible to perform all the suggested interventions and drug regimes outside hospital without compromising transportation times and good basic life support with oxygen. Rapid transportation is still the mainstay of the management of cardiac arrest in the pre-hospital setting. MANAGEMENT OF NON-SHOCKABLE RHYTHMS (asystole or PEA) Good basic life support should be commenced and remain continuous and the child ventilated with oxygen as soon as possible. 54 (Updated January 2010) THE MANAGEMENT OF CARDIAC ARREST Adrenaline 10 mcg /kg should be administered every 3-5 minutes. Throughout management, possible underlying causes should be sought (see figure 3.4). Hypovolaemia, tension pneumothorax and hypothermia should be considered. Other causes cannot generally be managed before hospital. Pulseless electrical activity (Figure 3.4) should usually be treated with rapid volume expansion (20 ml/kg of crystalloid or colloid) because hypovolaemia is the commonest cause. SHOCKABLE RHYTHMS Asynchronous electrical defibrillation should be carried out immediately at a dose of 4 joules/kg. Paediatric paddles (4.5 cm) should be used for children under 10 kg. One electrode is placed over the apex in the mid-axillary line, while the other is put immediately below the clavicle just to the right of the sternum. If only adult paddles are available for an infant under 10 kg, one may be placed on the infant’s back and one over the left lower part of the chest at the front. See Practical Procedures (Part VII). Refer to AED section for AED use. Following each shock, CPR should be resumed immediately, commencing with compressions. After 2 minutes, if the monitor still shows VF /Pulseless VT, a second shock of 4 J/kg should be administered and, if the rhythm remains shockable, a third shock of 4 J/kg is administered after another 2 minutes, this time giving adrenaline 10mcg/kg immediately before the shock. If the child remains in VF/VT after 3 shocks, 5mg/kg amiodarone should be given and the sequence of shock at 4J/kg – 2 minutes CPR continued until arrival at hospital. Adrenaline 10mcg/kg should be given immediately before alternate shocks. The child should be transported as soon as possible, if necessary stopping the ambulance to defibrillate the child. Oxygen and good basic life support must be continued throughout. During the resuscitation, the underlying cause of the arrhythmia should be considered. If VF is due to hypothermia then defibrillation may be resistant until core temperature is increased. If VF has been caused by drug overdose, then specific antiarrhythmic agents may be needed, so urgent transfer to 55 (Updated January 2010) THE MANAGEMENT OF CARDIAC ARREST hospital is required. POST-RESUSCITATION MANAGEMENT Once spontaneous cardiac output has returned, frequent clinical reassessment must be carried out to detect deterioration or improvement until arrival at hospital. All patients should have continuing assessment of: Pulse rate and rhythm Oxygen saturation The blood sugar should be measured and corrected if necessary Often children who have been resuscitated from cardiac arrest die hours or days later from multiple organ failure. In addition to the cellular and homeostatic abnormalities that occur during the preceding illness, and during the arrest itself, cellular damage continues after spontaneous circulation has been restored. This is called reperfusion injury and is caused by the following: Depletion of ATP Entry of calcium into cells Free fatty acid metabolism activation Free oxygen radical production Post-resuscitation management both before and after arrival at hospital aims to achieve and maintain homeostasis in order to optimise the chances of recovery. WHEN TO STOP RESUSCITATION If there have been no detectable signs of cardiac output, and there has been no evidence of cerebral activity despite up to 30 minutes of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, it is reasonable to stop resuscitation, and a suitably qualified practitioner may elect to do so. Exceptions to this rule include the hypothermic child (in whom resuscitation must continue until the core temperature is ◦ at least 32 C or cannot be raised despite active measures) and children who have taken overdoses of drugs. In these cases prolonged resuscitation attempts will be necessary and should always be continued for the full journey 56 (Updated January 2010) THE MANAGEMENT OF CARDIAC ARREST time to hospital. The decision to stop resuscitation, in reality, is usually taken after the child has arrived in hospital. The teaching in this section is consistent with the ILCOR and Resuscitation Council (UK), Resuscitation 2005. An enormous number of references have informed these guidelines which are available on the ALSG Web site for those who are interested. See details on the “Contact Details and Further Information” page. 57 (Updated January 2010) THE MANAGEMENT OF CARDIAC ARREST Asystole or PEA Establish cardiac arrest Ensure minimal interruptions in CPR with 100% oxygen IO or IV access Check blood sugar LMA, intubate for prolonged transfer or failure to ventilate only This is the most common arrest rhythm in children, because the response of the young heart to prolonged severe hypoxia and acidosis is progressive bradycardia leading to asystole. The ECG will distinguish asystole from ventricular fibrillation and electromechanical dissociation. The ECG appearance of ventricular asystole is an almost straight line; occasionally P waves are seen. Check that the appearance is not caused by an artifact, eg a loose wire or disconnected electrode. Turn up the gain on the ECG monitor, switch through leads. Adrenaline (Epinephrine) 10 micrograms/kg IO Consider and Manage Reversible Causes 2 minutes CPR Hypoxia Adequate airway, 100% oxygen 02 manage respiratory problems then transport. Hypovolaemia Fluid challenge 20ml/kg x1 then transport Hypo/hyperkalaemia Rapid transport Hypothermia Passive warming, no more than 3o shocks & no drugs until temp >30 C (3 shocks then transport) Tension pneumothorax Needle decompression then transport Tamponade (cardiac) Rapid transport Toxins Naloxone for opiates Glucagon for betablockers otherwise, rapid transport Thromboembolism Rapid transport If hypoglycaemic give 5ml/kg 10% dextrose Consider and correct reversible causes. Move to ambulance and transport to hospital Figure 3.4. Asystole and PEA algorithm Vascular access Intraosseous access (IO) is the recommended route for vascular access in cardiac arrest in young children. 58 (Updated January 2010) THE MANAGEMENT OF CARDIAC ARREST Adrenaline (epinephrine) Adrenaline (epinephrine) is the first line drug for asystole. The initial intravenous dose is 10 mcg/kg (0.1 ml/kg of 1:10 000 solution). This is given through a peripheral or intraosseous line followed by a normal saline flush (2 – 5 ml). If there is no vascular access, the endotracheal tube can be used, but absorption is erratic via this route. Ten times the intravenous dose (i.e. 100 mcg/kg) should be given via this route. The drug should be injected quickly down a narrow-bore suction catheter beyond the tracheal end of the endotracheal tube and then flushed in with 1 or 2 ml of normal saline. In patients with pulmonary disease or prolonged asystole, pulmonary oedema and intrapulmonary shunting may make the endotracheal route less effective. If there has been no clinical effect, further doses should be given intravenously or IO as soon as vascular access has been secured. Fluids In some situations, where the cardiac arrest has resulted from circulatory failure, a standard (20 ml/kg) bolus of fluid should be given if there is no response to the initial dose of adrenaline (epinephrine). The nature of the fluid is less important than the volume - crystalloid such as normal (0.9%) saline is suggested. Alkalising agents Children with asystole may be profoundly acidotic as their cardiac arrest has usually been preceded by respiratory arrest or shock. However, the routine use of alkalising agents has not been shown to be of benefit and these agents should be administered only in cases where alkalinisation may be helpful such as tricyclic overdose or hyperkalaemia. Bicarbonate is the most common alkalising agent currently available, the dose being 1 mmol/kg (1-2 ml/kg of a 8.4% solution). The tracheal route must not be used, and interactions with other drugs must be borne in mind. Second adrenaline (epinephrine) dose There is no convincing evidence that a tenfold increase in adrenaline (epinephrine) dose is beneficial in children and it may even lead to a worse neurological outcome. It should only be used exceptionally for a specific reason such as ß–blocker overdose. Adrenaline should be given every 3-5 minutes. 59 (Updated January 2010) THE MANAGEMENT OF CARDIAC ARREST Ventricular Fibrillation CPR with 100% O2 and minimal pauses until defibrillator ready Check monitor Ventilate with O2 LMA / Intubate DC Shock 4J/kg or AED (see note 2) 2 min CPR Check monitor Ventilate with O2 IO Access Check blood sugar Give 5ml/kg 10% dextrose if hypoglycaemic DC Shock 4J/kg or AED Consider and treat reversible causes 2 min CPR Check monitor This arrhythmia is uncommon in children but is commoner in those who are electrocuted, those with from hypothermia, those poisoned by tricyclic antidepressants, and those with cardiac disease. Dose Adrenaline (epinephrine) - 10 μg/kg Amiodarone 5mg/kg - maximum 300mg Lidocaine (Lignocaine): <12yrs – 500 μg/kg to 1 mg/kg >12 yrs 50-100mg (see formulary) Give drugs via IO route Ventilations at 10 per minute. Adrenaline then DC Shock 4J/kg or AED Consider and Manage Reversible Causes 2 min CPR Check monitor Amiodarone then DC Shock 4J/kg or AED If amiodarone is unavailable then lidocaine may be used (see below) 2 min CPR Check monitor Move to ambulance and commence transportation Hypoxia Adequate airway, 100% oxygen 02 manage respiratory problems then transport. Hypovolaemia Fluid challenge 20ml/kg x1 then transport Hypo/hyperkalaemia Rapid transport Hypothermia Passive warming, no more than 3 shocks & no drugs until temp >30oC (3 shocks then transport) Tension pneumothorax Needle decompression then transport Tamponade (cardiac) Rapid transport Toxins Naloxone for opiates Glucagon for betablockers otherwise, rapid transport Thromboembolism Rapid transport Adrenaline then DC Shock 4J/kg or AED Notes 2 min CPR Check monitor DC Shock 4J/kg or AED i.e. Adrenaline before every other shock 1. Move as soon as is logistically reasonable 2. An adult AED may be used in children over the age of 8 years. In children 1yr–8yrs an AED with paediatric attenuation should be used if available. In children under 1, nearly all had severe hypoxia and the use of AEDs remains controversial. 2 min CPR Check monitor Figure 3.5. Ventricular fibrillation algorithm 60 (Updated January 2010)