Qualitative Research on Immunization

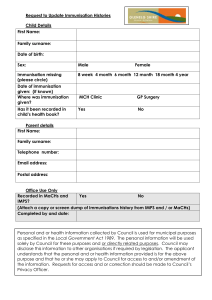

advertisement