risk, rents and regressivity

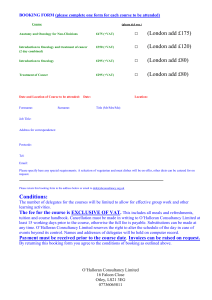

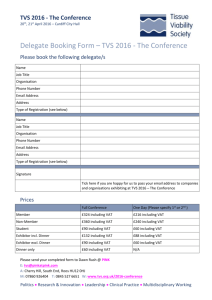

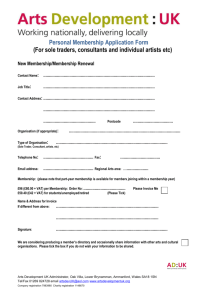

advertisement