The Impact of the NCEA on Student Motivation

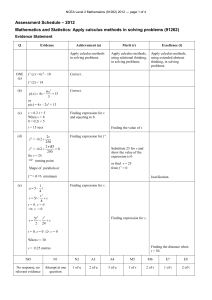

advertisement