Conservatism: Emphasis on the role of tradition as the basic

advertisement

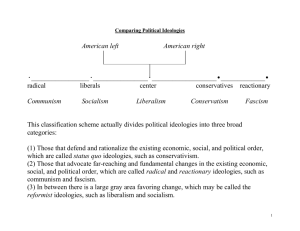

Honors World History The Age of the ism’s Mr. Soff Conservatism: Emphasis on the role of tradition as the basic underpinning for the rights of those in positions of authority. Rooted in the writings of Edmund Burke, whose Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) was widely read throughout Europe. Two components of Burke’s work were extremely popular in the Restoration period: 1). His attack on the principle of the rights of man and natural law as fundamentally dangerous to the social order and, 2). His emphasis on the role of tradition. Burke argued that the revolutionaries erred in thinking they could construct an entirely new government based on reason. Government had to be rooted in experience, which evolved over generations. Burke admitted the possibility of political change, but felt it must proceed slowly and cautiously. The “rights of man” could not stand alone as a doctrine based on nature and reason. The community too had rights, more important than those of any individual. Established institutions (the church, the government, the family) best represented the “proper” social order as faith, history, sentiment, and tradition needed to fill the vacuum left by the failures of reason and individual rights. Conservatism argued that only the smartest, most talented people (i.e. the aristocracy) should rule. On the continent a more extreme form of Conservatism appeared in the writings of Joseph de Maistre, an émigré from the French Revolution. De Maistre argued that the Church should stand as the very foundation of society because all political authority stemmed from God. De Maistre believed that monarchs should be extremely harsh with those who advocated even the slightest degree of political reform and that the “first servant of the crown should be the executioner.” Liberalism: Liberalism is deeply rooted in the French Revolution with Jefferson’s/Lafayette’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen serving as the basic creed. Nineteenth century liberals (being liberal has a different meaning today) wanted to protect the rights of the individual by limiting on the power of the government by emphasizing an individual’s rights to religious freedom, freedom of the press, and equality under the law. Liberals at the time were greatly influenced by Adam Smith’s economic theories in his Wealth of Nations. Smith advocated laissez-faire – minimal governmental regulation of the economy. Most liberals applauded the social and economic changes produced by the Industrial Revolution (since most liberals came from the rapidly expanding middle-class). Not all liberals followed Smith’s ideas. One of the most influential liberals of the nineteenth century was John Stuart Mill, who argued that the role of government is to provide “the greatest happiness for the greatest number.” Mill wrote the hugely influential Principles of Political Economy (1848) and argued that it may be necessary for the state to intervene and help workers achieve economic justice. Mill was also among the first to call for the granting of full equality for women. It was the liberals in Britain and France who took the lead in forming antislavery societies (civil liberties at home and slavery in the West Indies was intolerable). Although liberals wanted broader political participation, they were not necessarily advocates of democracy. Liberals didn’t like aristocrats but they also didn’t like the lower, uneducated, un-propertied classes. Liberals transformed the 18th century concept of aristocratic liberty into a new concept of privilege based on wealth and property rather than birth. Liberals want governments reformed so that educated, responsible citizens (like themselves) could participate. Nationalism: A population’s identity is defined by their connection with a nation and it is to this nation that they owe their primary loyalty. No longer is loyalty based on your village, your region, your family, etc. Nationalism is usually based on a common culture, common language, common traditions, common religion, or ethnic background. For example, the French live in France, the Germans in Germany, the Spaniards in Spain, the English in England, the Chinese in China, etc. Coming out of the French Revolution, the calling of all young men to military service (national conscription) helped create the idea of a citizen, whose primary loyalty lies not to the village or province, but to the nation. Nationalism became important in other parts of Europe in reaction to the expansion of France under Napoleon. In the German and Italian states, the desire to rid their lands of the French soldiers created a unifying purpose that helped establish a national identity. This growing national identity also had a literary component as writers such as the Brothers Grimm recorded old German folk tales to reveal a traditional German national spirit that was of a common past, whether you lived in Bavaria, Saxony, or any of the other German states. Nationalism was often tied to liberalism because many nationalists—like the liberals—wanted political equality and human freedom to serve as the foundation for a new state. Romanticism: Romanticism is often associated with Conservatism, although not all Romantics were conservative and not all Conservatives followed Romanticism. Those known as Romantics opposed the values and scientific narrowness of the philosophies of the Enlightenment and Scientific Revolution. Philosophy and science had reduced every subject to geometrical or mathematical models thereby ignoring feelings and imagination. Where the philosphes (like Rousseau, Voltaire, and Franklin) had often criticized religion and faith, the Romantics saw religion as basic to human nature and faith as a means to knowledge. Romanticism emphasized the glorification of the medieval past and the age of theocratic monarchies; artists looked to emotion rather than science or reason. In England, the poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth proposed discarding the formal rules of poetry and instead directed their writings toward revealing their emotional response to nature. Romanticism helped create a craze for anything medieval, in part inspired by the writings of Sir Walter Scott and Victor Hugo, both of who set their novels (Ivanhoe and the Hunchback of Notre Dame) in medieval times. Their work helped inspire the neo-gothic style in architecture, which explains why nearly every church built in the nineteenth century looks like it was built in the thirteenth. Britain’s Parliament and Big Ben are also examples of Romantic neo-gothic architecture. In painting, influential works such as Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1819) showed the deeply emotional nature of the Romantics. Gericault based his work on the true story of the sinking of a ship and the barbaric events that happened afterward (which included cannibalism). Even though he did not paint the ship’s survivors settling down to an afternoon snack on Ensign Johnson’s left leg, the turmoil aboard the raft does show the breakdown of human beings into their more animalistic state, contrasting sharply with the eighteenth century emphasis on man as a rational being. Socialism: The idea for Socialism, like the other ideologies we’re discussing, is rooted in the French Revolution. A number of radical Jacobins had the idea of political equality for all (Liberalism) and moving it to the next step: economic equality for all through the common ownership of all property. The impoverished working class wanted economic equality and they looked to the government (state) to regulate life and make it fairer for everyone. Early socialists believed that if workers were placed in the correct surroundings, they and their character would be improved. It was the poor environments of the slums that corrupted human nature. The early socialists were visionaries, ashamed of the increasingly wide gap between wealth and poverty and the plight of working class people in the cities. Karl Marx dubbed these socialists as “Utopian Socialists,” and he viewed these theorists with contempt because he felt they offered non-scientific, unrealistic solutions to the problems of modern society. Marxist Socialism (named after Karl Marx’s/Frederick Engel’s Communist Manifesto 1848), espoused more radical socialism. Communism, as it became known, implied the outright abolition of private property with everything belonging to the state. The Communist Manifesto would become the most influential political document in modern European history.