Dialect areas of the United States

advertisement

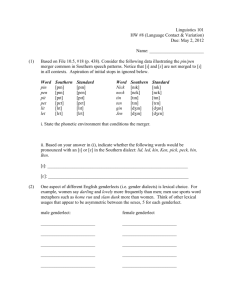

Udo Buffler, Birgit Lascho, Kai Schäfer, Alexander Schneider, Sarah Schneider, Daniela Thrasher Justus-Liebig-University, FB 05 – Department of English PS: English Dialects, Prof. Dr. Magnus Huber 1 1. Dezember 2005 American Regional Dialects Dialect areas of the United States This article is based on three different scholars and their approaches to define the major dialect regions of the United States and their results of investigating distinctive linguistic features of these regions. Hans Kurath, an American linguist with Austrian roots, started his investigation of the eastern U.S. in the 1930’s and identified three major dialect areas: Northern, Midland and Southern. He excluded the West because settlement-routes intermingled the eastern dialects. (1949) Craig M. Carver, an American dialectologist, stated that there are only two dialect areas: Northern and Southern. He rejected Kurath’s idea of a Midland area. Carver’s main contribution was to set up a linguistic Atlas for the entire USA (American Regional Dialects 1987) William Labov, another American linguist intended to simplify the methods of investigation. He overruled the fieldwork-methods used by Kurath and Carver mainly depending on lexical terms and variations. Labov started a national Telephone Survey (TELSUR) and brought up the Phonological Atlas of North America. The idea was to show sound-changes correlating to geography and to population. (1997) Chain-Shifts and Mergers The latest and obviously the most appropriate approach to the dialectolgical situation in the U.S. by W. Labov is indicated by the recognition of chain-shifts (vowel-shifts) and mergers (2 or more phonemes merge or collapse into one sound (either one of the two previous sounds, or another sound)). These are the two main types of sound changes. Udo Buffler, Birgit Lascho, Kai Schäfer, Alexander Schneider, Sarah Schneider, Daniela Thrasher Justus-Liebig-University, FB 05 – Department of English PS: English Dialects, Prof. Dr. Magnus Huber 2 1. Dezember 2005 The o/oh merger Map 1 shows the extent of this merger in speech production before /t/, as in cot vs. caught. The geographic appearance of this merger is quite broad it covers half the geographic area of the United States. Only the North, North Midland and Mid-Atlantic States where the population is high the o/oh sound is pronounced separately. The in~en merger This conditioned merger concerns the distinction between /i/ and /e/ before /m/ and /n/, as in pin vs. pen, him vs. hem. This is usually reflected in a high front vowel for both, so that both pin and pen sound like pin to speakers of other dialects. As a result, the two words are normally distinguished as ink pen and safety pin in these areas. Chain-Shifts The greatest difficulties for speech recognition are posed not by mergers but by chain shifts of vowels. Over the past two decades, two major patterns of chain shifting have been identified, which rotate the vowels of English in opposite directions. The Northern Cities Shift is found throughout the industrial inland North and most strongly advanced in the largest cities: Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, Cleveland, Toledo, Detroit, Flint, Gary, Chicago, Rockford. The shift begins when /æ/, the vowel of cad, moves to the position of the vowel of idea /i'/ (1). The vowel /o/ in cod then shifts forward so that it sounds like cad to speakers of other dialects (2). /oh/ in cawed moves down to the position formerly occupied by cod (3), /e/ in Ked moves down and back to sound like the vowel of cud (4), /cud moves back to the position formerly occupied by cawed (5), and /i/ in kid moves back in parallel to the movement of /e/ (6). Udo Buffler, Birgit Lascho, Kai Schäfer, Alexander Schneider, Sarah Schneider, Daniela Thrasher Justus-Liebig-University, FB 05 – Department of English PS: English Dialects, Prof. Dr. Magnus Huber 3 1. Dezember 2005 On the other hand, the Southern Shift, found throughout the Southern States, South Midland, and many other areas, moves vowels in an opposite direction. The shift begins when /ay/ becomes monophthongized and shifts slightly to the front (1). The nucleus of the diphthong /ey/ then falls along a non-peripheral track until it becomes the lowest vowel in the system (2). The nucleus of the diphthong /iy/ follows a parallel path towards mid-center position (3). The short front vowels /i, e/ shift forward and up until they reach the front peripheral positions formerly occupied by /iy/ and /ey/, and /æ/ moves in parallel (4). The nuclei of /uw/ and /ow/ then shift forward to front and center positions (5,6). /ohr/ (now most often merged with /owr/ ) moves up to high back position (7), and /ahr/ shifts up and back to the position that /ohr/ vacated (8). The Northern Cities Shift and the Southern Shift are both complex relations of 6 to 10 vowels. One of the goals of the Telsur project is to derive a small set of numerical parameters which can place each speaker's system within the overall configuration of the regional dialects of North America in a way that reflects both geographic and linguistic regularities. Two such parameters will only be mentioned here: æ/e reversal and e/o alignment. They are designed primarily as measures of participation in the Northern Cities Shift, but they also isolate Southern systems, since the movements of the Southern Shift are diametrically opposed to movements of the Northern Cities Shift. Udo Buffler, Birgit Lascho, Kai Schäfer, Alexander Schneider, Sarah Schneider, Daniela Thrasher Justus-Liebig-University, FB 05 – Department of English PS: English Dialects, Prof. Dr. Magnus Huber 4 1. Dezember 2005 Sociolinguistic differences – ethnicity and gender Race From a sociolingual perspective, what is popularly identified as „ethnicity” may be difficult to separate from various other factors such as region or class. Afro American Vernacular English (AAVE) represents the paradigmatic case for examining the role of ethnicity in dialect diversity. AAVE is for example strongly linked to social status within the community as well as to Southern regional English. Other linguistic varieties are for example only geographically linked to certain bilingual regions like Chicano English which is mostly spoken in the south western parts of the United States. Generally one can say, that the extent to which ethnic membership correlates with linguistic diversity varies from linguistic variable to linguistic variable, from race to race and in the race itself. Gender varieties Introduction/Background Knowledge: Historical development of “Gender and Language Variation”: In the past: male-female language differences in English were seen as uninteresting; this field has not traditionally been a central concern of dialect studies; Today: there exists and extensive collection of studies, anthologies, and books devoted exclusively to issues of language and gender in English (e.g. Deborah Tannen: “You Just Don´t Understand”) Cross-Sex Language Difference in Dialect Surveys: General Findings regarding male-female language differences: Fact 1: women tend to use more standard language features then men, whose speech tends to be more vernacular Fact 2: women adopt new language variants much earlier than men The contradiction between fact 1 and 2: women appear to be more conservative than men; they use more standard variants which often represent older language forms women appear to be more progressive then men because they adopt new variants more quickly; Fact 3: the patterning of male-female language differences depends not only on the language feature in question but also on the social class of the speaker Udo Buffler, Birgit Lascho, Kai Schäfer, Alexander Schneider, Sarah Schneider, Daniela Thrasher Justus-Liebig-University, FB 05 – Department of English PS: English Dialects, Prof. Dr. Magnus Huber 5 1. Dezember 2005 Explaining Cross-Sex Language Differences: The Prestige Approach: A: Labov (1984) explained that women are more prestige-conscious than men: Reason 1 (Labov): women are quicker to adopt innovative variants, which carry local prestige and which haven´t been in place long enough to acquire negative valuation in the lager community (be up to date) Reason 2 (Labov): women in the lower middle class are most likely to stigmatize features and adopt prestige features because members of this social class are more upwardly mobile than members of any other socioeconomic class Reason 3 (Labov): males tend to use more stigmatized variants in their speech than females; symbolic: males and females want to define themselves as either masculine or feminine (e.g. non-standard forms may symbolize masculinity and toughness) B: Trudgill (1983) goes a step beyond Labov; he asks why women are more prestige-conscious than men: Reason 1 (Trudgill): women want to transmit culture through childrearing Reason 2 (Trudgill): men and women have different occupational roles; men have traditionally been rated by their occupation; women have often been rated to a greater extend by how they appear; therefore the linguistic “cosmetic” of prestigious language may be more important for women than it is for men These reasons are not only theories. Labov´s and Trudgill´s notions that women´s linguistic behaviour can be explained in terms of their focus on social prestige are of widespread acceptance. Lexical and grammatical differences in American regional dialects 1. Lexical differences 1.1. Definition we talk about lexical differences in regional dialects if the same object is described by different labels by this process the meaning of words can change in two ways: it can be narrowed or broaded. Udo Buffler, Birgit Lascho, Kai Schäfer, Alexander Schneider, Sarah Schneider, Daniela Thrasher Justus-Liebig-University, FB 05 – Department of English PS: English Dialects, Prof. Dr. Magnus Huber 6 1. Dezember 2005 1.2. Examples: the words "creek" and "ditch" taken from the dialect spoken in the Outer Bank islands of North Carolina 1.2.1 Creek Other islands in the Outer bank bay in a common meaning Island of Overcake refers only to a specific body of water 1.2.2 Ditch Other islands in the Outer bank small river in general Island of Overcake refers only to the inlet which allows boats to enter the creek At both examples the meanings are narrowed, but the opposite is also possible. 2. Grammatical differences 2.1. Definition grammatical differences in regional dialects means that a special grammatical word category like the plural can be described by different word forms. In one dialect for example the plural could be marked by the suffix "s" and in another dialect it could be marked without the suffix "s". Other grammatical changes are also possible like the use of the “-ed”-ending in verbs, the use of the “-ing”-ending in verbs or the use of prepositions. 2.2. Example: The use of the plural-s in some dialects spoken in the Anglo-American South in some Anglo-American dialects the plural “-s” is used: The cats are nice. in some dialects spoken in the Anglo-American Southern the plural-s is eliminated by nouns indicating weights and measures if the plural noun is preceded by a specific number, since this number serves as a clear marker that the following noun is plural, thus making the “-s”-ending superfluous. Go about four mile_ up the road. Udo Buffler, Birgit Lascho, Kai Schäfer, Alexander Schneider, Sarah Schneider, Daniela Thrasher Justus-Liebig-University, FB 05 – Department of English PS: English Dialects, Prof. Dr. Magnus Huber 7 1. Dezember 2005 Some phonological aspects about different dialects Some selected features: Midland & West Rural Southern White rhotic conservative vowel sheme – have remained monophthongal vowel shift: o and au shift into an intermediate vowel: cot and caught are merged not to be fit into larger group New England non-rhotic (Boston, Eastern NE) car [ka:] park [pa:k] “southern drawl” southern shift triphtongization glide weakening pin/pen/merger northern shift: vowel shift: o and au shift into an intermediate vowel: cot and caught are merged (homophones) “ju” (jod-dropping): after [n] [d] [t] [s] [z] [l] new [n(j)u:], Tuesday [t(j)uzdeı] Some words as examples (vowel pronunciation, supported by audio-samples): GA kit Midland & West New England Rural southern white ɪ æ ɪ æ ɪ εə i æε α α α~ɒ α strut ʌ ɜ ə ɜ choice ɔɪ oɪ ɪ oi face eɪ εi eɪ εi ~ æi price αɪ ai > əɪ αɪ > əɪ ai ~ a:æ ~ a: north ɔɚ(r) æ a o æ ɔ (r) æ > εə a oɚ æ α a α~ɔ ɔo ~ ɒo ~ αo nurse ɚ ə ə (r) ɚ > ɐɚ > ɜi mouth aʊ əʊ aʊ > əʊ æɔ~æɒ~aɒ trap lot bath thought Udo Buffler, Birgit Lascho, Kai Schäfer, Alexander Schneider, Sarah Schneider, Daniela Thrasher Justus-Liebig-University, FB 05 – Department of English PS: English Dialects, Prof. Dr. Magnus Huber 8 1. Dezember 2005 Sources: Berg Flexner, Stuart: I hear America talking, N.Y. (1976) Carver, Craig M.: American Regional Dialects: A Word Geography, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press (1989) Fought, Carmen: Chicano English in Context, Houndmills (2002) Kortman, Bernd: English Linguistics: Essentials (Anglistik – Amerikanistik), Cornelsen Verlag (2005) Kortmann, Bernd, Schneider, Edgar W. (eds.): A handbook of Varieties of English, Vol. 1, Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter (2004), including the accompanying CD Poplack, Shana (ed.): The English History of American English, Malden, Mass. (2000) Rickford, John R.: Afro American Vernacular English, Malden, Mass. (1999) Viereck, Wolfgang /Karin, Ramisch, Heinrich: dtv-Atlas: Englische Sprache, dtv-Verlag (2002) Wolfram, Walt, Schilling-Estes, Natalie: American English, 2nd edition, Blackwell Publishing (2006) Internet-Sources: www.wikipedia.org (28th Nov 2005) www.evolpub.com/Americandialects(11th Nov. 2005) www.ling.upenn.edu/phono_atlas/ (26th Nov. 2005)