Fed Takes Foot Off the Gas

advertisement

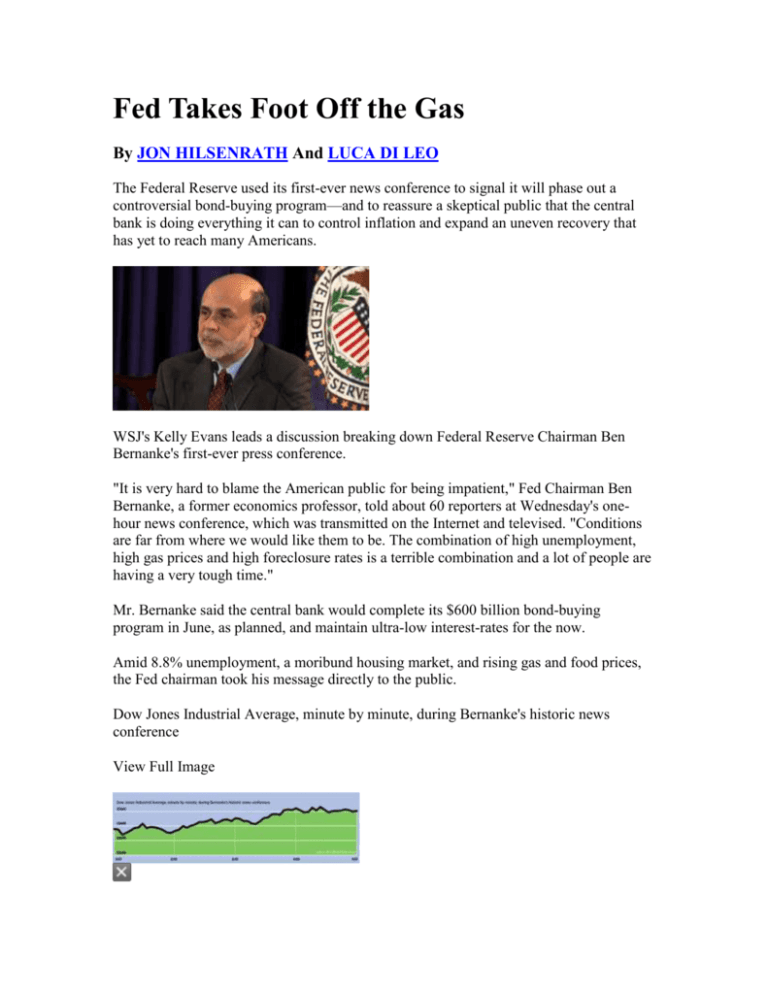

Fed Takes Foot Off the Gas By JON HILSENRATH And LUCA DI LEO The Federal Reserve used its first-ever news conference to signal it will phase out a controversial bond-buying program—and to reassure a skeptical public that the central bank is doing everything it can to control inflation and expand an uneven recovery that has yet to reach many Americans. WSJ's Kelly Evans leads a discussion breaking down Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke's first-ever press conference. "It is very hard to blame the American public for being impatient," Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, a former economics professor, told about 60 reporters at Wednesday's onehour news conference, which was transmitted on the Internet and televised. "Conditions are far from where we would like them to be. The combination of high unemployment, high gas prices and high foreclosure rates is a terrible combination and a lot of people are having a very tough time." Mr. Bernanke said the central bank would complete its $600 billion bond-buying program in June, as planned, and maintain ultra-low interest-rates for the now. Amid 8.8% unemployment, a moribund housing market, and rising gas and food prices, the Fed chairman took his message directly to the public. Dow Jones Industrial Average, minute by minute, during Bernanke's historic news conference View Full Image He aimed in part to better explain the thinking within a central bank whose reputation has been bruised by the recession and its aftermath. That reputation is especially important right now, because Mr. Bernanke needs to convince the public that he won't let inflation take off after pushing interest rates to near zero or employ unconventional measures, such as the bond-buying program, to boost growth. By ending the bond purchases, the Fed has effectively decided that it won't do more to boost growth, even though the economy appeared to stumble during the first quarter. Fed officials now will turn their attention to when the central bank might start raising interest rates. Mr. Bernanke made clear he isn't inclined to do that for a long time, unless the inflation outlook worsens. Financial markets, particularly riskier assets such as stocks and commodities, rose in response to the Fed's action and Mr. Bernanke's comments. The Dow Jones Industrial Average rose 95.59 points, or 0.76% to 12690.96, with the bulk of the gains coming after the Fed released its policy statement at 12:30 p.m., about two hours before the press conference began. Gold prices jumped 0.91% to $1516.70 an ounce, while silver surged 2.01% to $45.9640 an ounce. Investors punished the dollar. The euro rose more than 0.7% to nearly $1.48 against the greenback. The British pound rose to $1.66. Critics say the Fed is hastening the dollar's decline by flooding the financial system with so much of the currency through its bondbuying programs. Mr. Bernanke countered that the best medicine for the dollar in the long run was a faster-growing economy, which he is trying to promote with his policies. Treasuries didn't move much. The benchmark 10-year Treasury note ended the day yielding 3.368%, roughly matching its level before the Fed released its policy statement. Brett Arends and Dennis Berman give us their assessment on how Bernanke did in his first-ever press conference. The decision about when to raise interest rates will be challenging. The Commerce Department is expected to report Thursday that the economy grew slowly in the first quarter, at a subpar annual rate of less than 2%—a condition that could justify leaving rates very low. But with prices marching higher for oil, grain, and other commodities, the Fed is under increasing pressure to respond to inflation threats with higher rates. The Fed raised its inflation forecasts at the meeting. In January, Fed officials said they expected 1.3% to 1.7% inflation in 2011. Now, because of soaring gasoline prices, they expect inflation of 2.1% to 2.8%, but they expect it to drop back below 2% in 2012 and 2013. They forecast the unemployment rate, now 8.8%, to finish the year between 8.4% and 8.7%, and to finish 2012—just after the next presidential election—somewhere between 7.6% and 7.9%. "Bernanke handled himself very adroitly," said Michael Feroli, an economist with J.P. Morgan. "He didn't speculate on decisions that have not yet been made by the FOMC." The FOMC, or Federal Open Market Committee, is the decision-making body of the Fed. At the news conference, which capped two days of policy discussions with other Fed officials, Mr. Bernanke took questions in a calm, deliberative manner, seeming to gain confidence as he proceeded. His critics, however, weren't swayed by the performance, saying he once again avoided saying when the Fed will tighten policy to keep simmering inflation under control. "He's skilled. He's been dodging questions in Congress for a long time now," said Allan Meltzer, a Fed historian. WSJ's Kelly Evans leads a discussion about the impact of today's statement by the Federal Reserve and the decision to leave the Fed Funds target unchanged. While the Fed chief acknowledged the public's impatience, he also said there was little he could do to bring down gasoline prices, which he said were being driven up largely because of worries about oil supplies in the Middle East and strong demand from fastgrowing developing economies. "The Fed can't create more oil," he said. "We don't create the growth rates of emerging market economies." Measures of expected inflation in the bond market and in consumer surveys have recently been creeping up toward the high end of the range they have been in for several years. Mr. Bernanke made clear that one of his biggest concerns right now is that, if people expect inflation to go up, businesses may be quicker to raise prices and consumers more willing to pay them, and workers more likely to demand higher wages—turning the expectations into a self-fulfilling prophecy. But he said he was comfortable that the public's inflation expectations remained well anchored. Ending the bond-purchase program in June is now its next order of business. The Fed first announced its bond purchases in November 2008 as one of its many untested attempts to fight the then-worsening financial crisis. It ramped up the program in March 2009, allowed it to expire, and then resumed it in November when the economy appeared to lose momentum. View Slideshow Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, center, took questions at the press conference in Washington Wednesday. Fed officials for the most part believe the multiple rounds of purchases—known as quantitative easing—helped to ease financial conditions, lift the economy and fight off the threat of deflation, a decline in the overall level of prices. The latest round was accompanied by a soaring stock market and falling unemployment. Critics include some regional Fed bank presidents. Divisions have already surfaced within the Fed on the appropriate response to higher commodity prices, with a vocal minority of regional officials urging tighter credit this year to head off building inflation. Charles Plosser from the Philadelphia Fed and Richard Fisher from the Dallas Fed have been the most outspoken in warning about the dangers of raising rates too late. But they didn't dissent at the latest FOMC meeting. —Mark Gongloff contributed to this article.