Levinas, Plato, and the Desire for Transcendence

advertisement

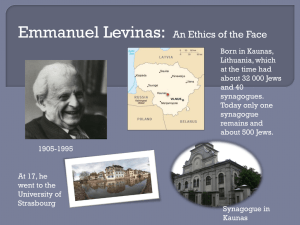

Emmanuel Levinas’ Renewal and Transformation of Plato’s Desire Part of the legacy of Emmanuel Levinas’ Totality and Infinity lies in the prominent distinction, although already made in Franz Rosenzweig’s The Star of Redemption, between the Same and the Other. The Same is defined by an intellectual cognition of entities in terms of their being. In contrast to this, Levinas phenomenologically describes the other in terms of a face that is never present, “knowable” only in the trace. By the trace, the realms of the Other and the Same “interact”. Even though critiques of Western Philosophy in terms of the Same are prominent within Totality and Infinity, Emmanuel Levinas wrote the book as an attempt to “return to Platonism” .1 In fact, when summarizing the content of Totality and Infinity for the Annales de l’Université de Paris, Levinas stated that “To show that the first signification emerges in morality . . . is to restrict the understanding of the reality on the basis of history; it is a return to Platonism” (121). Far from simply breaking from the philosophical tradition, Levinas contends that Totality and Infinity is a return to morality as first philosophy. To accomplish this feat, Levinas needed to restrict philosophy based in historical investigation. This move naturally lead him toward Plato’s ahistorical idealism. However, Levinas was not content to merely renew an ancient philosophical tradition. He sought to both renew and transform the Platonic tradition. This opens a quagmire. How can Levinas both break from the philosophical tradition while at the same time describe his philosophy as a return to its foundation, i.e. Platonism? Totality and Infinity, in Levinas’ own words, is a “return to Platonism”. Yet 1 Reprinted and Translated in Peperzak, Adriaan. Platonic Transformations: With and after Hegel, Heidegger, and Levinas. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1997, p.121. 2 at the same time, it is one of the most severe critiques of the philosophical tradition. So how can Totality and Infinity simultaneously break from the philosophical tradition while “return[ing] to Platonism”? Both Levinas’ break with the philosophical tradition and his return to Platonism can be seen in a close reading of Totality and Infinity. The book reveals both the break with philosophy and the return to Platonism primarily in two specific issues. First is Levinas’ renewal and transformation of Plato’s doctrine of the Same and the Other. Far from simply adopting Plato’s doctrine in renewed form, Levinas radically transforms it into the basis of an entirely new argument. Second is Levinas’ renewal and transformation of Plato’s analyses of desire found in the Symposium. Again, far from simply adopting desire as the need to fulfill something that is lacking, Levinas incorporates this concept into his own idea of an insatiable desire for the Other. By examining both Levinas’ renewal and transformation of the Platonic tradition we better understand how Levinas both breaks with the philosophical tradition while at the same time renewing and transforming its Platonic foundation. The Same and the Other At the heart of Totality and Infinity is the distinction between the Same and the Other. This distinction provides the structural basis for Levinas’ argument. 2 On the one hand, the Same is the realm of the philosophical tradition. It seeks to reduce everything 2 One need only to glance the table of contents of Totality and Infinity to see that its argumentation is structured around the doctrines of the Same and the Other. The Same is the realm of philosophy inspired by Plato. The Other is the realm of radical exteriority. Philosophy is the movement of the reduction of all objectivity to subjectivity, all exteriority to interiority. That which is different or other than the ego is assimilated, digested, and reused in the name of the ego. In this way, the ego becomes master over all things, subjecting all things to itself. This consumption of the exterior by the ego is the enjoyment of the world that characterizes the state of humanity. 3 exterior into the interior realm of cognition. Descartes’ famous statement in his second meditation, “Cogito ergo sum”, perfectly summarizes this movement. For Descartes, the subject exists as interior thought. Only on the basis of thought can a “bridge” of the exterior be crossed. This “bridge” is not a way for the interior to become exterior. Quite the opposite, the “bridge” allows for the exterior to be interiorized in terms of human cognition. Thus, in Descartes’ Meditations we see the assimilation of the exterior into the interior of human cognition. On the other hand, the Other is that which is ontologically different from the Same. The Other is not a realm, space, place, time, or object that can be reduced to human cognition. The Other defies any attempts at assimilation. It differs radically from anything the Cartesian subject can cognize. Although the distinction between the Same and the Other is integral to his argument, it is by no means original to Levinas. The distinction between the Same and the Other finds its first systematic exposition in the philosophy of Plato. Aware of this origin, Levinas purposely renews and transforms Plato’s distinction, making it the basis of his own philosophy. Plato employs the distinction between the Same and the Other as the basis of his own philosophy. However, he spells out this distinction in very few places. It is primarily found in his later dialogues, specifically, the Timaeus3 and the Theaetetus.4 In the Timaeus, Plato contextualizes the distinction between the Same and the Other within a dialogue regarding the creation of the universe. In that discussion, Plato 3 Plato. "Timaeus." In Readings in Ancient Greek Philosophy, edited by Mark C. Cohen, Patricia Curd, C.D.C. Reeve, 546-76. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2000. 4 Plato. Theaetetus. Translated by M.J. Levett. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishers, 1992. 4 describes that the universe was made from a “mixture of the Same, and then one of the Different, in between their indivisible and their corporeal parts, divisible counterparts” (35ab). Of these three elements that comprise the universe, the Same, The Different or Other, and the mixture of the two, it is the Same that serves as the paradigm for universal ordering. In fact, Plato goes on to describe how the mixtures were made into a “uniform mixture” by “forcing the Different . . . into conformity with the Same” (35ab). At the cosmic level, the distinction between the Same and the Other was transgressed when the Other was forced into conformity with the Same. The Other, as non-ordered, was forced into the rational ordering of the Same. In the Timaeus, Plato describes the distinction between the Other and the Same in an account of creation. In this account, the Other was forced to conform to the ordering of the Same. Emmanuel Levinas adopts Plato’s assimilation of the Other to the Same. But instead of using the reduction at the cosmic level, he employs the reduction at the micro level. For Plato, the reduction ultimately meant that chaos would be conquered by rational human cognition. The Different was reduced to something that human beings could comprehend through reason. However, for Levinas, the Same describes the philosophical traditional insofar as it was characterized by the reduction of all exteriority to the interiority of the subject.5 Even though he adopts the Platonic assimilation of the Other to the Same, Levinas employs assimilation as characteristic of the Same. Levinas would transform the distinction between the Same and the Other by arguing that within the realm of the Same, the reduction of exteriority to interiority happens phenomenologically prior to human cognition. 5 Levinas characterizes the Same as the inner psychic life of the subject. The Same is separated from everything else insofar as everything exterior is reduced to the interior life of the subject. As Levinas states, “The separation of the Same is produced in the form of an inner life, a psychism” (54). 5 In Totality and Infinity, Emmanuel Levinas argues against Martin Heidegger that the primary means of knowing is not utility, but enjoyment. As where the philosophical tradition from Plato through Descartes up to Husserl, emphasized objective rational cognition as the means for arriving at truth, Martin Heidegger deviated from this standard in Being and Time6 by arguing that the primary means of arriving at the truth was utilizing objects in accordance with their function. Using the tool in accordance with its proscribed function brought humanity closer to its truth than objective reasoning. Levinas agreed that objective cognition is a deviation from a more primal understanding of the world, but he did not accept Heidegger’s analysis wholesale. Instead, Levinas argued that Heidegger was mistaken in his emphasis upon utility. Addressing Heidegger head on Levinas states the following: The things we ‘live from’ are not tools, or even implements, in the Heideggerian sense of the term . . . they are always in a certain measure – and even the hammers, needles, and machines are—objects of enjoyment . . . ‘living from . . . “ delineates independence itself, the independence of enjoyment and of its happiness, which is the original pattern of all independence (110). Human beings do not use objects simply because they are suited for particular functions. The ultimate purpose for using those objects is to attain happiness. Humans use tools because they enjoy them. For Levinas, enjoyment is more primal than utility. The subject does not simply use the world, the subject enjoys it. Through enjoyment the subject establishes itself as separate not only from anonymous being but also other egos. 7 6 Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time: A Translation of Sein Und Zeit. Translated by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson. San Francisco: Harper San Francisco, A Division of Harper Collins Publishers, 1962. 7 Levinas’ extremely interesting article “On Escape” addresses this issue more fully. In it he argues that Western Philosophy is wrong to seek a fusion with beings. Instead the point is to escape the clutches of anonymous being. Levinas, Emmanuel. On Escape. Translated by Bettina Bergo. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003. 6 Unlike Descartes,8 who establishes subjectivity on objective thinking, Levinas argues that the ipseity of the subject is established on the basis of its assimilation of the exterior into the interior through enjoyment. Instead of a being a “thinking thing”, the subject is established primarily by enjoying its world. In the Theaetetus,9 Plato describes the difference between the Same and the Other as relative to the difference between the materiality and immateriality. As materiality has one type of determination, immateriality has another. Likewise, the Same has its own determination that differs from the Other. Unlike the Timaeus, where the Other was brought into conformity with the Same, here Plato allows the Same and the Other to rest in a dialectical tension. Neither the Same is reduced to the Other nor the Other to the Same. Instead, they are related to each other through their differentiation. As Plato has Theaetetus say: You mean being and not-being, likeness and unlikeness, same and different; also one, and any other number applied to them. And obviously too your question is about odd and even, and all that that involved with these attributes; and you want to know through what bodily instruments we perceive all these with soul (185c) Socrates responds further down: . . . while the soul considers some things through the bodily powers, there are others which it considers alone and through itself (186a). Even though the material and immaterial are related in difference, the immaterial is higher in ontological reality. The immaterial can function both independent of the material and also within its confines. But the material is dependent upon the immaterial. That is why Socrates tells Theaetetus that some things are known by the soul through the 8 Contra Descartes Meditations on First Philosophy, thinking is not the foundation of subjectivity. Instead, Levinas argues that “it is not knowing but enjoyment, and, as we shall say, the very egoism of life” (112). Descartes, Rene. Discourse on Method and Meditations on First Philosophy. Translated by Donald A Cress. 4th ed. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishers, 1998. 9 Plato. Theaetetus. Translated by M.J. Levett. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishers, 1992. 7 powers of both the body and the soul but others are by the soul alone. The soul, as immaterial, can know things that body by itself cannot (185c). Even though the Same and the Other have different ontological determinations, they are related to each other in their differentiation.10 Emmanuel Levinas both renews and transforms the distinction between the Same and the Other found in Plato. Levinas renews the Platonic emphasis upon the reduction of the Other to the Same. He renews the idea of the reduction of the Other to the Same but employs it as the reduction of the exterior to the interior, an event that characterizes the philosophical tradition as the realm of the Same. In the Same, everything exterior is reduced to the interiority of the subject. Levinas also transforms the distinction by claiming an absolute alterity of the Other in respect to the Same. The Other remains infinitely transcendent, infinitely foreign, his face in which his epiphany is produced and which appeals to me breaks with the world that can be common to us, whose virtualities are inscribed in our nature and developed by our existence. Speech [the relation between the Other and the Same] proceeds from absolute difference (194). The Other is irreducible to human cognition; it cannot be known objectively. It is not a thing to be assimilated into the subject’s interior cognition. In Sensibility and Singularity: The Problem of Phenomenology in Levinas, John Drabinski argues that here also Levinas is drawing from the Platonic tradition. He argues that in the relation between the Same to the Other described in terms of intentionality, the subject intends 10 In the Sophist (254b-256d), the Other and the Same are irreducible. The categories of the Same and the Other are discussed in while debating the properties of motion. The Same and the Other are never reduced nor related to each other. Unlike the Theaetetus, the distinction between the Same and the Other designate ontological categories that are neither linked dialectically nor coupled “to[gether] as straightforward contradiction” (Peperzak, 114). The only “link” that the Same might have with the Other consists in their absolute separation (Peperzak, 114). The Sophist describes the distinction between the Same and the Other as irreducible unrelated ontological categories. 8 toward an exterior that surpasses “the boundaries of possible cognition” (112).11 Levinas renews Plato’s distinction between the Same and the Other by making the reductive aspects characteristic of the Same. He transforms Plato’s distinction by making each category exist in an absolute separation of alterity. Levinas recontextualizes Plato’s distinctions within his own philosophy. The renewed and transformed doctrine of the Same and the Other demonstrates Levinas’ claim that Totality and Infinity is a “return to Platonism”. In Totality and Infinity Levinas both renews the Platonic doctrine of the Same and the Other but at the same time transforms it into his own philosophy. For Plato, the Same was the privileged realm which the Other was made to conform in the Timaeus. The Theaetetus used the Same and the Other to describe different ontological determinations related in their differences. Levinas renews this tradition by making the distinction between the Same and the Other the organizing principle of his philosophy. The Same is characterized by the reduction of all exteriority to interiority. The Other is characterized by an absolute alterity from the Same. In Totality and Infinity, Emmanuel Levinas both renews and transforms Plato’s distinction between the Same and the Other. Plato, Levinas and Desire Using the distinction between the Same and the Other as their basis, both Plato and Levinas make desire the focal point of their philosophy. Desire is the medium through which the subject transcends the realm of materiality (Plato) and the Same 11 Drabinski, John E. Sensibility and Singularity: The Problem of Phenomenology in Levinas. Edited by Dennis J. Schmidt, Suny Series in Contemporary Continental Philosophy. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2001. 9 (Levinas) into the immaterial (Plato) and the Other (Levinas). In the Symposium12, Aristophanes details how desire arises from the lack of one’s soul mate. In Totality and Infinity, Levinas describes how desire is operative in both the realm of the Same and in the transcending movement the subject to the Other. A close reading of the Symposium reveals the nature of desire in Plato’s philosophy of transcendence. It also reveals that nature of desire as arising from an unfulfilled need. Plato’s desire is renewed and transformed by Levinas’ philosophy of transcendence as a movement from the Same to the Other. The Symposium describes desire as emerging from an unfulfilled need. The speech of Aristophanes explains that humans were originally attached to each other. However, after an unsuccessful attack upon the gods, they were punished by being split in half (190b). Out of this split “the innate desire for human beings for each other started” (191c). Humans began innately desiring each other in order to “make one out of two and to heal the wound of human nature” (191c). The split of humans into two separate beings created a need for something that was lacking. Edith Wyschogrod describes this split as the boundary between the immanent and the transcendent.13 The soul mate, the other half of the immanent being remains transcendent from the subject. Humans desire to complete themselves by bringing the transcendent back into immanence. On account of this, it is not surprising to see Plato describing human life as characterized by desire seeking to fulfill its most innate need. Desire seeks to fill what is needed. As Socrates remarks to Agathon: 12 Plato. The Symposium, Penguin Classics. London: Penguin Group, 1999. Wyschogrod, Edith. Emmanuel Levinas: The Problem of Ethical Metaphysics. New York: Fordham University Press, 2000, p.127. 13 10 So this and every other case of desire is desire for what isn’t available and actually there. Desire and love are directed at what you don’t have, what isn’t there, and what you need (200e1-3). Even though it first appears in the speech of Aristophanes, Socrates embraces the idea that desire arises out of a lack of fulfillment. Desire seeks was it not actually there but is available. Plato’s philosophy of desire begins with desire emerging from an unfulfilled need within humanity. Through an analogy of a staircase, Plato explains that the ultimate fulfillment of human desire occurs in the transcendence of the soul into the Good. Building on the idea that desire seeks to fulfill what it lacks, Plato describes a staircase of desire in which the fulfillment of one desire directly leads to another. These desires continue to increase until the soul transcends the material into the Good. The staircase begins with desire for other human beings then moves to ontologically higher objects ending in a desire for the good itself. As Diotima14 tells Socrates: Like someone using a staircase, he should go from one to two and from two to all beautiful bodies, and from beautiful bodies to beautiful practices, and from practices to beautiful forms of learning which is of nothing other than that beauty itself so that he can complete the process of learning what beauty really is (211c). The desire became innate to humanity when humans were split fails to find its ultimate fulfillment in another human being. Instead, it moves past that human onto ontologically higher and more beautiful objects. This movement continues until the soul sees beauty itself. But notice the role of learning plays in this movement. Learning as a cognitive event marks the transition from one step to another that ultimately leads to transcendence. As mentioned earlier, desire seeks to fulfill a need. In For an excellent discussion of the role of Diotima in Symposium with reference to Plato’s influence upon Levinas’ doctrine of materinity see: Sanford, Stella. "Masculine Mothers? Maternity in Levinas and Plato." In Feminist Interpretations of Emmanuel Levinas, edited by Tina Chanter, 180-202. University Park: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001, p. 191-195. 14 11 the case of a human being, its ultimate need is its return to the Good. The memory of the soul’s prior vision of the Good, which Plato describes in the Pheadrus15, remains within the human soul. Thus, when the soul sees a beautiful body it desires to make that body its own. But making an external object a part of the soul is a cognitive activity (211c). The soul, as immaterial, sees the idea of the body. That idea triggers the memory of the Good causing the soul to desire what it once possessed but now needs, the vision of the Good. The body is assimilated into the soul through the cognition of its idea. But the cognition of the idea does not ultimately satisfy the need for the Good. As a result the soul pursues beautiful practices and so forth until it reaches the Good itself. But nonetheless, the desire of the soul finds its ultimate fulfillment a cognitive transcendence of objective reality into Goodness itself.16 Emmanuel Levinas renews Plato’s doctrine of desire as assimilation by objective cognition in his doctrine of the Same. As mentioned earlier, the Same is the realm of assimilation of exteriority to interiority. Also mentioned earlier was that Plato described this assimilation taking place in objective cognition. Contra Plato, Levinas described the assimilation of objects not as cognition but as enjoyment. It is through enjoyment that the subject encounters the truth of the object. It is also by enjoyment that the subject appropriates its world for its own purpose. This appropriation, assimilation is a direct renewal of Plato’s doctrine of desire as cognitive assimilation. However, Levinas alters 15 Plato. Phaedrus. Translated by Alexander Nehamas and Paul Woodruff. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 1995. 16 Like Plato and Descartes, Levinas describes the good as beyond being. To reach the good one must transcend the realm of the Same cf. Critchley, Simon. "Introduction." In The Cambridge Companion to Levinas, edited by Simon adn Robert Bernasconi Critchley, 1-32. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. 12 the doctrine by claiming that the truth of the exterior is not encountered cognitively but as it is enjoyed. The transformation of Plato’s doctrine of desire occurs along a different path. Instead of confining desire to the Same, Levinas makes desire the means of transcending the Same. He transforms the transcending aspects of Plato’s desire from cognitive assimilation to desire for exteriority. As Levinas states: Metaphysics or transcendence is recognized in the work of the intellect that aspires after exteriority, that is, Desire. But the Desire for exteriority has appeared to us to move not in objective cognition but in Discourse . . . (82). Desire for exteriority is the work of the intellect as it seeks the Other. The difference between the Same and the Other mentioned previously now plays a significant role. The radical alterity of the Other transforms desire from a simple assimilation to desire that opens to the unknown, the radically different. Contra Plato, Levinas does not see desire as the fulfillment of the subject’s need. Desire is not based upon a lack that humanity feels as an innate desire. Instead, this desire is for something radically different from the subject and its needs. Levinas transforms Plato’s desire from assimilation into a movement toward the radically Other. Conclusions Levinas’ Totality and Infinity is both a renewal and transformation of the Platonic tradition. He renews Plato’s distinction between the Same and the Other. He transforms it by making the Same and the Other absolutely different instead of assimilating the Other to the Same. He also renewed and transformed the Platonic emphasis upon desire as the vehicle toward transcendence. Levinas renews that tradition by making desire the central focus of transcendence. However, he transforms the tradition by making the Same, in the 13 subject, transcend into the Other. Levinas’ philosophy can be read as a “return to Platonism” insofar as Levinas both renews and transforms the Platonic tradition Even though Emmanuel Levinas’ philosophy is a sharp critique of the Western Philosophical tradition, it remains a work within the Western Philosophical tradition. Levinas’ work is thoroughly influenced by Plato. His arguments are philosophical arguments dealing with philosophical problems. His methodology is philosophical. And his conclusions are philosophical. A reading of Levinas that emphasizes his critiques of philosophy to the neglect of his debt to Plato fails to see the profound impact the philosophical tradition plays in his philosophy. Levinas renews and transforms the Platonic tradition in his book Totality and Infinity. When read closely, the book reveals a significant debt to the philosophical tradition that it sets out to critique. Even though he is one of its sharpest critics, demonstrating Levinas’ renewal and transformation of the Platonic tradition allows us to better appreciate Levinas’ place within Western Philosophy. 14 Works Cited Critchley, Simon. "Introduction." In The Cambridge Companion to Levinas, edited by Simon adn Robert Bernasconi Critchley, 1-32. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. Drabinski, John E. Sensibility and Singularity: The Problem of Phenomenology in Levinas. Edited by Dennis J. Schmidt, Suny Series in Contemporary Continental Philosophy. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2001. Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time: A Translation of Sein Und Zeit. Translated by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson. San Francisco: Harper San Francisco, A Division of Harper Collins Publishers, 1962. Katz, Claire Elise. "Reinhabiting the House of Ruth: Exceeding the Limits of the Feminine in Levinas." In Feminist Interpretations of Emmanuel Levinas, edited by Tina Chanter, 145-70. University Park: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001. Levinas, Emmanuel. On Escape. Translated by Bettina Bergo. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003. ———. Totality and Infinity. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1998. Moyaert, Paul. "The Phenomenology of Eros: A Reading of Totality and Infinity, Iv.B." In The Face of the Other & the Trace of God: Essays on the Philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas, edited by Jeffrey Bloechl, 43-61. New York: Fordham University Press, 2000. Peperzak, Adriaan. Platonic Transformations: With and after Hegel, Heidegger, and Levinas. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1997. ———. To the Other: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas. Edited by Arion Kelkel, Purdue Series in the History of Philosophy. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, 1993. Plato. Phaedrus. Translated by Alexander Nehamas and Paul Woodruff. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 1995. ———. Plato's Sophist. Translated by William S. Cobb. Savage: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1990. ———. Republic. Translated by G.M.A. Grube. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 1992. ———. The Symposium, Penguin Classics. London: Penguin Group, 1999. 15 ———. Theaetetus. Translated by M.J. Levett. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishers, 1992. ———. "Timaeus." In Readings in Ancient Greek Philosophy, edited by Mark C. Cohen, Patricia Curd, C.D.C. Reeve, 546-76. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2000. Sanford, Stella. "Masculine Mothers? Maternity in Levinas and Plato." In Feminist Interpretations of Emmanuel Levinas, edited by Tina Chanter, 180-202. University Park: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001. Wyschogrod, Edith. Emmanuel Levinas: The Problem of Ethical Metaphysics. New York: Fordham University Press, 2000.