Northern Cape Province - State of the Environment South Africa

advertisement

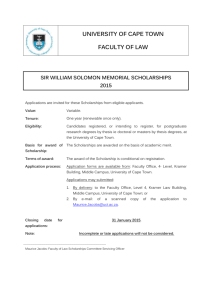

Northern Cape State of the Environment Report 2004 Land Specialist Report Northern Cape State of the Environment Report 2004 Land Specialist Report Final Version Prepared for: Department of Tourism, Environment & Conservation Private Bag X6102 Kimberley 8300 Project Manager: Abe Abrahams January 2005 Prepared by: Shamini Naidu and Linda Arendse CSIR Environmentek P O Box 17001 Congella 4013 This report forms part of a series of specialist reports produced for the 2004 Northern Cape State of the Environment Report. Cover Picture courtesy of Northern Cape Tourism Authority. The production of this report was made possible with a generous donation from the National Department of Environmental Affairs & Tourism through the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD). Table of Contents 1 Background ....................................................................................................... 1 2 Introduction to Land ......................................................................................... 2 3 Land Issues in the Northern Cape ..................................................................... 3 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 4 Land in the Northern Cape ................................................................................ 4 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 5 Land Degradation ........................................................................................... 3 Desertification ................................................................................................ 3 Land Use ....................................................................................................... 3 Land Ownership ............................................................................................. 4 Land cover ..................................................................................................... 4 Land degradation ........................................................................................... 7 Soil Salinisation ............................................................................................ 13 Desertification .............................................................................................. 15 Land Restitution ........................................................................................... 17 Responses ........................................................................................................ 18 5.1 5.2 5.3 International responses ................................................................................ 18 5.1.1 United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification ............................ 18 5.1.2 United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity ................................. 18 5.1.3 United Nations Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora ...................................................................... 18 National responses ....................................................................................... 19 5.2.1 National Environmental Management Act (Act 107 of 1998) .................. 19 5.2.2 Conservation of Agricultural Resources Act (Act 43 of 1983) .................. 19 5.2.3 National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Bill ........................... 19 5.2.4 National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act (Act 57 of 2003) ................................................................................................. 19 5.2.5 National Forests Act (Act 84 of 1998) ................................................... 20 5.2.6 Restitution of Land Rights Act (Act 22 0f 1994) .................................... 20 Provincial responses ..................................................................................... 20 5.3.1 Land Care South Africa ....................................................................... 20 6 Summary of Land ............................................................................................ 21 7 References ....................................................................................................... 22 8 Acknowledgements ......................................................................................... 24 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 1 BACKGROUND The Northern Cape Department of Tourism, Environment and Conservation (DTEC) (formerly the Department of Agriculture, Land Reform, Environment and Conservation (DALEC)) appointed CSIR to compile the 2004 Northern Cape State of the Environment (SoE) Report. The project process was divided into three phases, namely: Phase 1: Issues identification; Phase 2: Selection of Key Environmental Indicators; and Phase 3: Compilation of the 2004 SoE Report. During this process, both specialists and stakeholders were given the opportunity to contribute to the project. Phase 1 entailed the selection of key environmental issues, described as topics of strategic concern that will influence the environmental sustainability of the Province. A literature review of relevant and available information sources on environment was used to create a preliminary list of key environmental issues, which was reviewed at a stakeholder workshop convened in Kimberley on 9 December 2003. The broad key environmental issues were prioritised and related issues were highlighted, forming the final list of key environmental issues that was sent out for stakeholder comment. The broad key environmental issues identified in Phase 1 were then used as the basis for the development of a set of key environmental indicators in Phase 2. Specialist input was used to develop a proposed set of indicators. These environmental indicators, like the environmental issues, were grouped into broader categories, called ‘themes’. Although not every environmental issue listed has an indicator associated with it, the indicators selected for a theme provide the general understanding of the particular theme and allow the reader to gain insight into environmental trends within that theme. The draft set of key environmental indicators from Phase 2 was presented at a stakeholder workshop in Kimberley on 19 January 2004. During the workshop, stakeholders were given the task of reviewing and finalising the indicators for either one or two themes. A handout of questions regarding the relevance and practicality of each indicator was used to guide the group discussions. Comments and suggestions as well as details of additional data sources were captured in answer sheets by a member of each group, and shared in the feedback session that followed. The finalised set of key environmental indicators was sent out for stakeholder comment. Phase 3 of the project involved the compilation of the SoER, where each of the themes was investigated through a separate specialist study. Specialists were involved in compiling the draft studies, which were then subjected to a review. During this phase the specialists made use of the environmental indicators in their theme to generate an understanding of the complex interactions occurring in the Northern Cape environment. These individual specialist reports will be used to compile the popular and web versions of the 2004 Northern Cape SoER. This document provides the results of one of these specialist studies. It represents only one of a series of seven specialist reports produced for this project. 1 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 2 INTRODUCTION TO LAND The Northern Cape Province forms part of the former Cape Province and includes a number of communal areas previously known as Coloured reserves (Hoffman et al, 1999). While it is the largest province in South Africa, it is also the most sparsely populated. The Northern Cape is characterised by very hot summers and very cold winters (South Africa, 2003). Its arid nature has resulted in activities such as stock and game farming being more widespread than crop farming. Mining is also an important activity and the Province is the diamond centre of South Africa, with Kimberley as its capital. A large portion of the Orange River catchment area falls within the Northern Cape, which provides for a healthy agricultural industry. The area is noted for its vineyards whilst the predominant land use is stock and game farming (Hoffman et al, 1999). However, mining is the prime income generator. In 1888, the diamond industry was formally created with the establishment of De Beers Consolidated Mines. Diamonds are also extracted from the beaches and coastal areas (South Africa, 2003). The food and processing industry is slowly growing in the Northern Cape for local and export markets (South Africa, 2003). The Province has several national parks and conservation areas including the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park South Africa together with the Gemsbok National Park in Botswana is Africa’s first transfrontier game park, known as the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park (South African Consulate General, 2003). The last remaining San (Bushman) people live in the Kalahari area of the Northern Cape. The area along the Orange and Vaal rivers, are rich in San rock engravings (South Africa Government online, 2003). The landscape is characterised by vast arid plains with haphazard rocky outcrops. The western coastal region, which receives small amounts of winter rain, is dominated by succulent shrubs. The interior of the Province has a mixture of low shrubs and grasses (Hoffman et al, 1999). Wind and sheet erosion is extensive with salinisation (build-up of salt within the soil) affecting the majority of the Province (Hoffman et al, 1999). Soil salinisation, which is usually a problem in arid areas, often results from irrigated agriculture. Water used for irrigation contains trace amounts of salt, and when water evaporates from the soil surface or from the leaves of plants, it leaves the salt behind. Salinisation can also occur in the absence of irrigation where there is a naturally high salt content in the soil, which is characteristic of the Northern Cape. Bush encroachment and changes in species composition are the most serious problems affecting the land (Hoffman & Ashwell, 2001). Alien plant invasions are also severe in many parts of the Northern Cape. An example is Prosopsis species which consumes more than 200 million m3 of water per year (Hoffman et al, 1999). These species are considerably reducing the amount of groundwater available for farmers and rural communities. This specialist report provides a review of the state of land in the Northern Cape and is based on actual and modelled data obtained for the Province. 2 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 3 LAND ISSUES IN THE NORTHERN CAPE 3.1 Land Degradation Land degradation results in a significant reduction in the productive capacity of the land. Human activities such as agricultural mismanagement, overgrazing, fuelwood consumption, industry and urbanisation, as well as natural disasters, could all contribute to land degradation (UNEP, 2002). Land degradation is defined by Hoffman & Ashwell, (2001) as the loss of biological or economic productivity of an area primarily caused by human activities. The Northern Cape is predominantly arid and thus, only 2% of the land is used for crop farming. When crop farming is undertaken, proper irrigation systems are required to ensure healthy growth of the crop (Hoffman et al, 1999). The majority of the Province is used for stock farming including cattle, sheep or goat farming and mining whilst only 3.98% is reserved for conservation (Hoffman et al, 1999). Overgrazing is therefore one of the main causes of land degradation in the Northern Cape (DEAT, 2002). Mining has had serious negative environmental consequences in cases where it has been conducted without due recognition of the need to mitigate negative impacts (Northern Cape Provincial Government, 2002a). Alien plant invasions are posing a threat to the rich flora of the region (DEAT, 2002). The Northern Cape is also one of the worst affected areas in terms of bush encroachment which implies that large areas of grazing land are lost, species diversity is reduced and habitats are transformed (DEAT, 2002). These land use activities all contribute to a loss of vegetation cover, soil erosion and ultimately land degradation. Land degradation is thus, an important issue to rural communities and farmers that depend on the land for their livelihood. 3.2 Desertification Desertification refers to land degradation in arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas resulting from various factors such as climatic variation and human activities (UNCCD, 2003). Land degradation includes bush encroachment, loss of vegetation cover as well as change in species composition (GEM, 2002). In some cases, desertification follows localised overgrazing which leads to a loss of vegetation cover. The continuation of these poor land management practices causes degraded land to coalesce and become desertified (Hoffman & Ashwell, 2001). In South Africa the main desertification problems lie across large parts of the Northern Cape. This is due to the dry and arid characteristics of the Northern Cape. It should also be acknowledged that desertification is strongly linked to poverty and food security as a result of the social and economic importance of natural resources and agriculture to people living in poverty (UNCCD, 2003). This is especially true of the Northern Cape since the majority of the people live below the poverty line and have no choice but to overexploit the land (Hoffman et al, 1999). 3.3 Land Use Different land uses have varying effects on the ecological functioning of the land. It is therefore necessary to understand the different land use activities in order to effectively combat soil erosion, overgrazing, loss of vegetation cover and desertification. The predominant land use activities within the Northern Cape are mining and sheep, goat, cattle and game farming. Mining is slowly decreasing in the Province and retrenched workers often 3 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 purchase livestock to earn a living thus ultimately contributing to increased land degradation (Hoffman et al, 1999). Crop farming accounts for 2% only of the land used (Hoffman et al, 1999). This is primarily due to the climatic conditions experienced in the Province. In the past mining caused considerable conflict in the Northern Cape. The controversy began because of the granting of permits to small mining enterprises on Canteen Koppie (SAEP, 2003). In addition, diamond mining has been the root of many problems, including diamond smuggling activities (Third Word Traveller, 2004). 3.4 Land Ownership The land reform process is currently in progress in the Northern Cape and consists of land restitution, redistribution and tenure reform. Land restitution involves returning land which was lost due to racially discriminatory laws. Land restitution can also be achieved through monetary compensation (DLA, 2003). Land redistribution enables disadvantaged people to buy land, while land tenure reform aims to bring all people occupying land under one system of landholding (DLA, 2003). There are a number of issues relating to land tenure and access to land which pose a major obstacle to the development and management of land. Almost all the land in the Northern Cape is privately owned (DWAF, 2004). In the past, state agricultural land has been made available to emerging commercial farmers, in the form of leasing, outright sale and access to grazing land (Northern Cape Provincial Government, 2002b). By the end of 2003, the Northern Cape had processed 2 606 land claims out of 2 773 (International Marketing Council, 2003). In 2002, the Northern Cape Government successfully settled a land claim with the San and Mier communities. The land was situated in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park and 25 000 hectares of land was handed over to the San and Mier communities (Northern Cape Provincial Government, 2002b). The San and Mier communities entered into a contractual arrangement with the park authorities to manage the land on behalf of the San and Mier people (Northern Cape Provincial Government, 2002b). The Northern Cape recently launched the Land Redistribution for Agricultural Development (LRAD) programme which is designed to reduce rural poverty (Northern Cape Provincial Government, 2001). The LRAD programme targets previously disadvantaged people in rural areas to improve their standard of living by enabling them to manage their own farms effectively. 4 LAND IN THE NORTHERN CAPE 4.1 Land cover Land use is an important factor contributing to the condition of the land since land use impacts on land cover, which in turn affects the condition of the land. Different uses have varying effects on the integrity of the land. The land cover indicator is a state indicator that provides information on the current state of land cover in the Province (Thompson, 1999). It has been derived by the CSIR for the National Land Cover Database and is differentiated into a number of categories. The data are given a high confidence rating as it is based on satellite imagery which is then verified in the field by evaluating a series of grid-point locations in terms of the actual and classified land-cover types. Table 1 depicts the area (ha) and percentage area (%) for each land cover type, while Figure 1 illustrates the different land cover types in the Northern Cape (Thompson, 1999). 4 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 Table 1: Land cover types for the Northern Cape (Thompson, 1999) Land cover description Barren rock Cultivated: permanent-commercial dryland Cultivated: permanent-commercial irrigated Cultivated: temporary-commercial dryland Cultivated: temporary-commercial irrigated Degraded: shrubland & low Fynbos Degraded: thicket & bushland Degraded: unimproved grassland Dongas & sheet erosion Forest Forest & Woodland Forest Plantations Herbland Improved grassland Mines & Quarries Shrubland & Low Fynbos Thicket & bushland Unimproved grassland Urban/built-up land: commercial Urban/built-up land: industrial/transport Urban/built-up land: residential Urban/built-up: residential (small holdings: bushland) Urban/built-up land: residential (small holdings: shrubland) Waterbodies Wetlands Unclassified Total Area (ha) % 157469.4 0.4 638.9 0 34760.4 0.1 100545 0.3 130184 0.4 75560 0.2 43379.9 0.1 136022.2 0.4 63812.2 0.2 139.9 0 99939.1 0.3 2474.3 0 242872.3 0.7 2372.8 0 28735.5 0.1 25253446.2 69.7 5153920.2 14.2 4335807.3 12 1108 0 3936.4 0 21706.7 0.1 1118.9 0 0 0 57724.9 0.2 294934.8 0.8 10.3 0 36243188 100 5 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 Figure 1: Land cover types for the Northern Cape (Thompson, 1999) 6 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 Most of the Province is dominated by vast open areas of natural vegetation (69.7% of the total area is covered by shrublands and low fynbos). These areas are characterised by low, woody, self supporting, multi-stemmed plants that branch at or near the ground and are usually between 0.2 and 2 m in height. Typical examples of this type of vegetation include low Fynbos, Karoo and Lesotho (alpine) plant communities (Mudau, pers comm., 2003). A further 14.2% of the Northern Cape is dominated by thicket vegetation and bushlands. This type of cover can be described as tall, woody, self-supporting, single or multi-stemmed plants (branching at or near the ground), that have no clearly definable structure. The plant communities are essentially indigenous species, growing under natural or semi-natural conditions. Self-seeded exotic species along riparian zones may also be included in this category (Mudau, pers comm., 2003). A total of 0.7% of the Province is classified as degraded whilst 0.2% is dongas and sheet erosion areas. In addition, 12% of the land cover in the Province is unimproved grasslands characterised by less than 10% tree and/or shrub canopy cover, with greater than 0.1% of total vegetation cover. The plant communities are largely indigenous species growing under natural or semi-natural conditions which are dominated by grass-like, non-woody, rooted herbaceous plants (Mudau, pers comm., 2003). Urbanisation in the Province is relatively low (0.1%). However, it should be noted that these figures are based on the 1994/5 National Land Cover Database and may change in the new land cover map currently being developed by the CSIR. The New National Land Cover Database has been designed to accommodate the needs of a wide variety of potential users and it also conforms, as far as possible, to the land-cover classification standards proposed for the international AFRICOVER project of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 4.2 Land degradation Land degradation is defined as “reduction or loss, in arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas, of the biological or economic productivity and complexity of rainfed cropland, irrigated cropland, or range, pasture, forest and woodlands. This results from land uses, or from a combination of processes arising from human activities, and habitation patterns” (UNCCD, 1995 in Hoffman & Ashwell, 2001). The land degradation indicator is based on three indices that were developed in an effort to resolve South Africa’s problems of land degradation (Hoffman et al, 1999). The indices form part of a NAP for South Africa and include: The combined degradation index (CDI); The soil degradation index (SDI); and The vegetation degradation index (VDI). The study was undertaken by the National Botanical Institute (NBI) as the first step in the formulation of the NAP. The NAP is a requirement of South Africa’s ratification of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD, 2003). A total of 367 magisterial districts were evaluated and an SDI and VDI for South Africa were developed. The SDI and VDI together form the CDI (Hoffman et al, 1999). The first component of the NBI study comprised an assessment of soil degradation in the magisterial districts. Soil degradation was divided into erosive forms such as water and wind erosion, and non-erosive forms such as acidification and salinisation (Hoffman et al, 1999). 7 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 The second component concerned veld degradation and six main types of veld degradation were identified including: Loss of cover; Change in species composition; Bush encroachment; Alien plant invasions; Deforestation; and A general category of “Other”. The land degradation indicator will therefore measure the percentage of each magisterial district of the Northern Cape that falls into the different land degradation classes as defined by Hoffman et al (1999). It is an impact indicator and confidence in the data was given a high rating. However, the NBI study was conducted in 1999 and the extent/status of land degradation in the Northern Cape could since have changed. Table 2 and Figure 2 illustrate the degraded areas in the Northern Cape using the combined degradation index. Figure 3 and 4 present the VDI and the SDI respectively (Hoffman et al, 1999). Table 2: Percentage of the Northern Cape land area in each degradation category (CDI) (Hoffman et al, 1999) Categories of Degradation Insignificant Light Moderate Extreme Value Range % Area < 72 24.2 72-277 21.2 277-482 30.3 > 482 24.2 As is evident from Table 2 and Figure 2, the overall measure of land degradation in the Province is “insignificant” to “light”. Approximately 30% is moderately degraded whilst less than half of the Province is categorised by “light” degradation. Only 24.2% of the Province is “extremely” degraded. Results from the NBI investigation concluded that the Northern Cape is one of the least degraded provinces in South Africa (Hoffman et al, 1999). However, veld degradation was found to be serious, since the Province has one of the third highest provincial veld degradation indices in South Africa. It was found that change in species composition and bush encroachment1 were the most common problems (Hoffman et al, 1999). Gordonia and Fraserburg had the highest veld degradation index values (Figure 3). It should be noted that veld degradation has decreased to an extent in the Province due to an increase in good management practices, government sponsored schemes and bush clearing (Hoffman et al, 1999). Agricultural extension services, farmer study groups, drought subsidies and strict application of agricultural legislation have also assisted in reducing degradation in the Northern Cape (Hoffman et al, 1999). However, issues still to be resolved according to Hoffman et al (1999), include insufficient access to land, poor infrastructure, and lack of education, finance and government support. Soil degradation on the other hand was not perceived to be a serious problem; Prieska and Britstown were found to have the highest provincial indices of soil degradation (Figure 4). These areas are predominantly characterised by wind and sheet erosion and salinisation (Hoffman et al, 1999). 1 Bush encroachment refers to the transformation of a grass-dominated vegetation type into a woody species-dominated type. 8 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 Overall, land degradation is not a serious problem in the Northern Cape but, there are eight areas within the Province that require priority attention. These areas are commercial farming areas and are as follows (Hoffman et al, 1999): Britstown; Gordonia; Prieska; Carnarvon; Hay; Williston; Fraserburg; and Hopetown. This is fairly significant, when considering the potential for desertification as farmlands are most at risk for desertification (Hoffman & Ashwell, 2001). It should also be noted that the degraded areas in Figure 2 closely correlate with the degraded areas presented on the land cover map (Figure 1). 9 Figure 2: Map depicting land degradation in the Northern Cape based on the combined soil degradation and veld degradation indices (Hoffman et al, 1999) 10 Figure 3: Map depicting veld degradation in the Northern Cape (Hoffman et al, 1999) 11 Figure 4: Map depicting soil degradation in the Northern Cape (Hoffman et al, 1999) 12 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 4.3 Soil Salinisation Soil salinisation is a problem in the Northern Cape, particularly in areas where irrigated agriculture is practised. This state indicator shows the extent of salt affected soils in the Province. In areas where rainfall is approximately five to ten times less than the potential evaporation, salts derived from rock weathering, bio-cycling, evaporation and atmospheric deposition may accumulate in sub- and bottomland soils2. Under higher rainfall regimes and poor or impeded soil drainage conditions, lateral leaching of dissolved solids in the groundwater along slopes may also result in bottomlands being slightly enriched in salts (ARC-ISCW, 2004). In saline soils, the restricting effect of the osmotic pressure of the salts on water uptake by plant roots may affect the growth of non-salt tolerant plants. Sodicity results in adverse structure in soils (ARC-ISCW, 2004) and this may have a negative effect on plant growth. (A sodic soil is a soil with a low soluble salt content and a high exchangeable sodium percentage (usually ESP > 15) (Soil Classification Working Group, 1991). Soil salinity and sodicity may lead to a loss in crop production (Badenhorst, 2002) and may affect the long term agricultural potential of land in the Northern Cape. Soil salinisation is caused by poor drainage and it can be treated by implementing drainage measures in affected areas. A map of salt affected soils3 in the Northern Cape can be found in Figure 5. There are three main categories of salt affected soils and these categories are further divided into different classes (refer to Table 3). Table 3: Main categories of salt affected soils, classes associated with each category and the area that falls into each class of salt affected soils (ARC-ISCW, 2004). Area (km2) Saline Saline-Sodic Sodic Non-Saline Slightly Saline Moderately Saline Non-Alkaline Saline-Sodic Alkaline Saline Sodic Sodic Total area 176849 48818 3208 51626 78937 3132 362571 % 48.78 13.46 0.88 14.24 21.77 0.86 100 According to Table 3 above, 63.12 % of the Northern Cape can be classified as saline. This could be due to naturally occurring salts in water which has accumulated in the soil, natural soil or geological processes (e.g. rock weathering) or it could be induced by certain agricultural practices. The map of salt affected soils (Figure 5) does not show major occurrences of natural soil salinity and sodicity. Due to low sample density, soil salinity associated with riverine lowlands and irrigated areas, has not been shown (ARC-ISCW, 2004). Data confidence is rated as low since a realistic situation may not be reflected due to the quality of the data that was used (ARC-ISCW, 2004). 2 Sub-soil refers to underlying surface soil and bottomland soil is a lowland soil formed by alluvial deposit around a lake basin or a stream. 3 The map is based on electrical conductivity (ds/m), pH, exchangeable sodium percentage (ESP), and geological and mineral resources coverage. These were physically superimposed and interpreted, making use of best available knowledge. 13 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 Figure 5: Salt affected soils in the Northern Cape (ARC-ISCW, 2004) 14 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 4.4 Desertification The Northern Cape is arid with 2% of the land used for crop farming, 96% used for stock farming (including beef cattle, sheep, goats, and game), and 1% for conservation (Hoffman and Ashwell, 2001). Mining activities utilise part of the remaining land although exact figures are not mentioned (Hoffman et al, 1999). The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification in Countries Experiencing Serious Drought and/or Desertification, particularly in Africa (UNCCD) defines desertification as ‘land degradation in arid, semi-arid and dry subhumid areas resulting from various factors, including climatic variations and human activities’ (UNCCD, 1994). These areas of the world are called ‘affected drylands’. These aridity classes set out by the UNCCD are defined by calculating the ratio of mean annual precipitation (MAP) to potential evapotranspiration (PET). This indicator is a state indicator depicting the extent of affected drylands over the total area of the Northern Cape. Affected drylands are areas in which the ratio of MAP to PET falls within the range 0.05 to 0.65 (Hoffman & Todd, 1999 in Hoffman et al, 1999). The extent of affected drylands in the Northern Cape is depicted in Table 4 and Figure 6 which provides the area and percentage of the Province that falls into each aridity zone. Table 4: The area and percentage of the Northern Cape that fall into the five aridity zones (Schulze et al, 1997) Aridity class Hyper-arid Arid Semi-arid Dry sub-humid Humid MAP:PET < 0.05 0.05 – 0.2 0.2 – 0.5 0.5 – 0.65 > 0.65 Area (km2) 26648.21 300573.46 34977.01 0 0 Percentage of Province (%) 7.4 83.0 9.7 Affected Drylands 0 0 Approximately 93% of the Northern Cape can be classified as affected drylands, with 7.4% of the Province having a MAP: PET ratio below the limit for areas that are defined as affected drylands. This is an indication that most of land in the Northern Cape is potentially susceptible to desertification and should be managed in such a manner as to prevent land degradation from increasing, and to protect the land resources from desertification. Data confidence is rated as high. 15 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 Figure 6: The distribution of the aridity classes over the Northern Cape. The aridity classes are defined by calculating the ratio of MAP to PET (Schulze et al, 1997) 16 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 4.5 Land Restitution4 There have been 2 773 land claims submitted in the Northern Cape, and the Land Claims Commission had processed 2 606 of these by the end of 2003 (International Marketing Council, 2003). This indicator shows the land restitution projects that have been settled in the Northern Cape, the area of land that has been allocated under each project and the number of households that have been allocated land per project. Table 5 indicates that 3 997 645.19 ha of land has thus far been allocated to people under the Land Reform process. (Only cases where land has been involved are reflected in Table 5; those cases where people have decided to receive financial compensation are not reflected.) The households that are mentioned in Table 5 are not necessarily currently settled on the land. In these cases, there are some community members who have already settled on the land but the rest of the community members are waiting for the planning for establishment of townships and the building of houses to be completed. The only case where the community has been settled completely on the land is Riemvasmaak in 1994 (Mokomele, pers comm., 2004). It is not clear what the average number of people is per household, it is therefore difficult to give an indication of what impact the settled people will have on the areas where they have been settled. The land uses that the communities will adopt, combined with the current condition of the land, will play a role in determining the impact that they will have on the land. Data confidence is rated as medium. Table 5: Land restitution in the Northern Cape: Projects settled from 1994 to 2003 (Mokomele, pers comm., 2004) Project Area (hectares) Riemvasmaak Groenwater Skeyfontein Kono Ronaldsvlei Hartswater Schmidtsdrift (Batlhaping) Schmidtsdrift (Griqua claim) Khomani San (two claims) 74 562.81 166 11 849.39 500 12 957.76 500 10 685.24 400 3 71 1447.00 300 249.15 440 31 816.18 800 Not quantifiable 36 891.21 200 25 000.00 297 7 000.00 Not verified 27 000.00 10 218.12 800 1 657.10 380 6 821.64 178 22 489.59 214 3 997 645.19 5175 Mier (two claims) Majeng Bucklands Grootvlakfontein Khuis Total Households 4 The indicator was previously called Land Reform but has since been renamed to Land Restitution because the only data available on Land Reform was restitution claims 17 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 5 RESPONSES 5.1 International responses 5.1.1 United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification in Countries Experiencing Serious Drought and/or Desertification, particularly in Africa (UNCCD) has been established to address land degradation in arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas of the world. The UNCCD aims to promote effective action through innovative local programmes and supportive international partnerships (UNCCD, 2004). South Africa became a signatory to the UNCCD in 1995 and is obliged to develop a NAP to combat desertification. South Africa is in the process of finalising its NAP. 5.1.2 United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity The objectives of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) are: The conservation of biodiversity; The sustainable use of biological resources; and The fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the use of genetic resources (DEAT, 2003b). As a signatory to the Convention, South Africa is required to develop national strategies, plans and programmes for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. South Africa has, in response to the Convention, embarked on a process to develop a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP). This Plan will build on the 1997 White Paper on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of South Africa’s Biological Diversity (DEAT, 1997) by translating policy goals into an implementation plan, with firm targets, clear roles and responsibilities, realistic timeframes and measurable indicators. The NBSAP will help identify priorities to ensure that South Africa’s biological diversity is preserved for future generations, that biological resources are used wisely and that all South Africans appreciate, care for and benefit from our biological diversity (DEAT, 2003a). 5.1.3 United Nations Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is an international agreement whose primary objective is the control of international trade in endangered species of flora and flora and their products. CITES provides a framework which is to be respected by each party to the Convention, but each Party has to adopt its own domestic legislation to ensure that the Convention is implemented at a national level (CITES, 2004). The National Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism (DEAT) is responsible for coordinating the implementation of the Convention and acts as a channel of communication 18 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 between South Africa, the CITES Secretariat and other Parties. The provincial authorities are responsible for implementing the Convention in their respective provinces (DEAT, 2003c). At provincial level, the local law enforcement units enforce legislation with regard to CITES. This Convention plays an important role in controlling the trade in endangered species of flora and fauna in the Province. 5.2 National responses 5.2.1 National Environmental Management Act (Act 107 of 1998) The National Environmental Management Act (NEMA) provides for co-operative environmental governance by establishing principles for decision making on matters affecting the environment, institutions that will promote co-operative governance and procedures for coordinating environmental functions exercised by organs of state. It recognises that all South Africans have the right to an environment that is not harmful to his or her health or well-being and that the State must protect and fulfil the socio-economic and environmental rights of all and strive to meet the basic needs of the previously disadvantaged communities (Republic of South Africa, 1998b). 5.2.2 Conservation of Agricultural Resources Act (Act 43 of 1983) The purpose of this Act is to provide for control over the utilization of the natural agricultural resources of South Africa, in order to promote the conservation of the soil, water resources, and vegetation, and the combating of weeds and invader plants (Republic of South Africa, 1983). 5.2.3 National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act (Act 10 of 2004) This Act provides for the management and conservation of South Africa’s biodiversity within the framework of NEMA. It provides for: (a) (b) (c) (d) 5.2.4 The protection of species and ecosystems that warrant national protection; The sustainable use of indigenous biological resources; The fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from bio prospecting involving indigenous biological resources; and The establishment of a South African National Biodiversity Institute (Republic of South Africa, 2004a). National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act (Act 57 of 2003) The framework in which this legislation is to be implemented is provided for in NEMA, where environmental principles are set out and sections common to other legislation in the suite are located. This Act seeks to bring the system of protected areas in line with the Constitution and legal order, as well as the policies and programmes of the Government. This Act provides for the establishment of a representative system of protected areas as part of the national strategy to protect South Africa’s biodiversity and to ensure that the sustained biodiversity benefits future generations. It further provides for the participation by communities in conservation and its associated benefits, and for co-operative governance in the management of protected areas (Republic of South Africa, 2003). 19 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 This Bill, when enacted, will impact on the way that land in the Northern Cape is set aside for conservation and the manner in which that conserved land is managed. 5.2.5 National Forests Act (Act 84 of 1998) This Act provides for (amongst others): The sustainable management of all forest types (including woodlands); The monitoring and reporting on the state of forest resources; Setting aside of protected areas; and The promotion of rights of access for recreational and cultural purposes (Republic of South Africa, 1998a). These measures may play an effective role in proactively protecting land in the Northern Cape which may be susceptible to land degradation or desertification. 5.2.6 Restitution of Land Rights Act (Act 22 0f 1994) This Act provides for the restitution of land rights to persons or communities who were disposed of land under or for the purpose of furthering the objects of any racially based discriminatory law (Republic of South Africa, 1994). There have been 2 773 claims for land restitution submitted in terms of this Act in the Northern Cape. The implementation of this Act will therefore have an impact on land use patterns and management in the Province. This Act also makes provision for people who have been disposed of land to gain security of tenure and this may have an effect on the way that communal land is managed in the Province. 5.3 Provincial responses 5.3.1 Land Care South Africa Land Care is a community-based and government supported approach to the sustainable management and use of agricultural natural resources. The overall objective of Land Care is to optimise productivity and the sustainability of natural resources, leading to a greater productivity, food security, job creation and a better quality of life for all. The National Land Care Secretariat co-ordinates the National Land Care programme in consultation with relevant National or Provincial departments as well as the wider community. Land Care projects or programmes are implemented and funded by government departments, parastatals, non-governmental organisations, community-based organisations, communities and individuals. A number of Land Care projects have been implemented in the Northern Cape. Some of these have focussed on the management of grazing land, upgrading of fences and water points, eradication of alien plants, restoration of degraded land and stabilisation of dunes (Land Care South Africa, 2004). 20 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 6 SUMMARY OF LAND The Northern Cape Province is an arid province which is susceptible to land degradation and desertification. Policies and programmes are required to promote the sustainable management of land resources in the province. Mining has played a major role in shaping the economic development of the Province, but has also had a negative impact on land resources in certain parts of the Province. The following issues were identified as being the key issues relating to land resources in the Province: Land degradation; Desertification; Land use; and Land ownership. These issues were measured by the use of the following indicators: Land cover; Land degradation; Soil salinisation; Desertification; and Land restitution. An assessment of the Land Cover indicator reflects that most of the Province is dominated by open areas of natural vegetation consisting of shrublands and low fynbos. A small percentage (0.7%) is classified as degraded, while 0.2% of the area is affected by dongas and sheet erosion. The land degradation indicator shows that 30.3% of the Province can be classified as moderately degraded and 24.2% of the land falls into the extremely degraded category (according to the combined soil and veld degradation indices). This indicates that just over half the Province falls into the moderate and extreme degradation categories. This is a cause for concern and measures need be devised to ensure that the situation does not worsen. Soil salinisation is a problem in the Province, particularly in areas where irrigated agriculture is practised. Soil salinisation is represented using a map of salt affected areas for the Province; however, this map may not reflect the true situation due to the quality of the data that was used to produce this map. Salinisation of soils can lead to a change in soil structure and a loss of agricultural potential which is not easily reversible. Programmes to prevent salinisation of soils should therefore be instituted and farmers should be assisted to enable the application of the most appropriate practices for their farming conditions. The desertification indicator shows that 92.6% of the Province can be classified as ‘affected drylands’ with a further 7.4% having a MAP: PET ratio lower than that of the ‘affected drylands’. The Province is therefore very susceptible to desertification and additional programmes to promote sustainable land management should be established. The NAP to combat desertification and land degradation should take the Northern Cape as one of its focal areas in which to implement interventions. 21 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 There have been 2 773 claims for land restitution submitted in the Northern Cape and the Land Claims Commission had processed 2 606 of these by the end of 2003 (International Marketing Council, 2003). The Land Restitution indicator shows that 3 997 645.19 ha of land is being claimed. Concerns have been raised over the changes in land use that may take place as a result of people being resettled on land as part of the Land Reform programme. The Department of Land Affairs, together with the provincial and local authorities should ensure that appropriate and sustainable land management systems are implemented in areas where people are resettled. 7 REFERENCES Agricultural Research Council - Institute for Soil, Climate and Water (ARC-ISCW). 2004. Overview of the status of the Natural Agricultural Resources of South Africa. ARC-ISCW Report No. GW/A/2004/13. Badenhorst, J.W. 2002. Soil Conservation Report on Sub-Surface Drainage for the Financial Year 2001/2002. Report compiled for the Northern Cape Department of Agriculture, Land Reform, Environment and Conservation. CITES. 2004. What is http://www.cites.org/eng/disc/what.shtml CITES? [Online]. Available at: DEAT. 2003a. National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan. Newsletter: November 2003. DEAT. 2003b. Convention http://www.environment.gov.za on Biological Diversity. [Online]. Available: DEAT. 2003c. What is CITES? [Online]. Available: http://www.environment.gov.za DEAT. 2002. Environmental indicators for the National State of the environment reporting. [Online]. Available at: www.ngo.grida.no/soesa/nsoer/issues/land/state2.htm DEAT. 1997. White Paper on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of South Africa’s Biological Diversity. Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism. DLA. 2003. Land reform programmes. Department of Land Affairs. [Online]. Available at: http://land.pwv.gov.za/home.htm DWAF. 2004. Northern Cape Strategy. Department of Water Affairs and Forestry. [Online]. Available at: http://www.dwaf.gov.za/Forestry/Community %20Forestry/Where/Northern%20Cape/ GEM. 2002. South Africa’s implementation of the UN Convention to Combat Desertification. Group for Environmental Monitoring. [Online]. Available at: www.gem.org.za/html/document/unconv.pdf Hoffman, T. Todd S. Ntshona, Z. & Turner, S. 1999. A National Review of Land Degradation in South Africa. [Online]. Available at: http://www.nbi.ac.za/landdeg/index.htm 22 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 Hoffman, T. & Ashwell, A. 2001. Nature Divided: Land Degradation in South Africa. University of Cape Town. International Marketing Council. 2003. Land claims successfully settled. [Online]. Available at: http://www.safrica.info/what_happening/news/landclaims_210103.htm Land Care South Africa. 2004. Frequently asked Questions. http://www.nda.agric.za/docs/landcarepage/FAQ.htm [Online]. Available: Mokomele, P.M. (pers comm.) 2004. Department of Land Affairs, Regional Land Claims Commission - Free State and Northern Cape. Mudau, H. (pers comm.). 2003. Remote Sensing Specialist, Project Manager - NLC 2000 Northern Cape Provincial Government. 2002a. Agriculture, Land Reform, Environment and Conservation Budget Speech 2002/2003 - MEC Rooi. [Online]. Available at: http://www.northern-cape.gov.za/docs/sp/showsp.asp?ID=144 Northern Cape Provincial Government. 2002b. Mbeki to hand over San Land. [Online]. Available at: http://www.northern-cape.gov.za/docs/nz/shownz.asp?ID=88 Northern Cape Provincial Government. 2001. Development. [Online]. Available cape.gov.za/current/projects.lrad.asp Land Redistribution for Agricultural at: http://www.northern- Republic of South Africa. 2004a. National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act, Act 10 of 2004. Pretoria: Government Gazette. Republic of South Africa. 2003. National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act, Act 57 of 2004. Pretoria: Government Gazette. Republic of South Africa. 1998a. National Forests Act, Act 84 of 1998. Pretoria: Government Gazette. Republic of South Africa. 1998b. National Environmental Management Act, Act 107 of 1998. Pretoria: Government Gazette. Republic of South Africa. 1994. Restitution of Land Rights Act, Act 22 of 1994. Pretoria: Government Gazette. Republic of South Africa. 1983. Conservation of Agricultural Resources Act, Act 43 of 1983. Pretoria: Government Gazette. SAEP. 2003. Mining and the Environment. Southern Africa Environment Page. [Online]. Available at: http://www.save.org.za/Mining/mining.htm Schulze, R.E., Maharaj, M., Lynch, S.D., Howe, B.J. and Melvil-Thomson, B. 1997. South African Atlas of Agrohydrology and Climatology. Water Research Commission, Pretoria. Soil Classification Working Group. 1991. Soil Classification. A Taxonomic System for South Africa. Memoirs on the Agricultural Natural Resources of South Africa No. 15. A Report on a 23 2004 NC SoER – Land Specialist Report 6 of 7 Research Project Conducted under the Auspices of the Soil and Irrigation Research Institute, Department of Agricultural Development, Pretoria. South Africa. 2003. The Cape Provinces. [Online]. http://www.safrica.info/ess_info/sa_glance/geography/cape.htm Available at: South Africa Government online. 2003. The land and its people. [Online]. Available at: http://www.gov.za/yearbook/2002/nc South African Consulate General. 2003. Northern Cape. [Online]. http://www.southafrica-newyork.net/consulate/provinces/northerncape.htm Available at: Third World Traveller. 2004. Conflict Diamonds are Forever. [Online]. Available at: http://www.thirdworldtraveler.com/weapons/Conflicit_Diamonds_MAK.html Thompson, M. W. 1999. South African National Land-Cover Database Project. Data Users Manual: Final Report (Phases 1, 2, and 3). CSIR client report ENV/P/C 98136 UNCCD. 1994. Text of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. [Online]. Available: http://www.unccd.int/convention/text/convention.php UNCCD. 2003. United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification in Countries Experiencing Serious Drought and/or Desertification, Particularly in Africa. United Nations Secretariat for the Convention to Combat Desertification, Bonn, Germany. [Online]. Available at: http://www.unccd.org UNCCD. 2004. The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification: An Explanatory Leaflet [Online]. Available: http://www.unccd.int/main.php UNEP. 2002. Global Environment Outlook: Past, Present and Future Perspectives. United Nations Environment Programme, Earthscan Publications Ltd, London. 8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to acknowledge contributions from the following people: Tim Hoffman, University of Cape Town; Avishkar Koosialee, CSIR; Arjoon Singh, CSIR; Gavin Fleming, CSIR; Marjan van der Walt, ARC Institute for Soil, Climate and Water; Jan Schoeman, ARC Institute for Soil, Climate and Water; Jan Badenhorst, Northern Cape Department of Agriculture, Land Reform, Environment and Conservation; and Pete Mokomele, Department of Land Affairs, Regional Land Claims Commission Free State and Northern Cape. 24