In the Rockies, Pines Die and Bears Feel It

advertisement

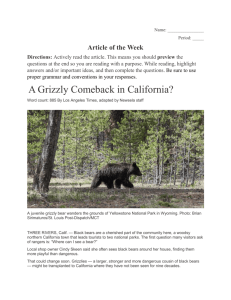

January 30, 2007 In the Rockies, Pines Die and Bears Feel It By CHARLES PETIT Jesse Logan retired in July as head of the beetle research unit for the United States Forest Service at the Rocky Mountain Laboratory in Utah. He is an authority on the effects of temperature on insect life cycles. That expertise has landed him smack in the middle of a debate over protecting grizzly bears. You just never know where the study of beetles will take you. Dr. Logan seems, in fact, to be on a collision course with the federal government, in the debate over whether to lift Endangered Species Act protections from the grizzly bears in and around Yellowstone National Park. The grizzly population in the greater Yellowstone area is estimated to be at least 600. The population is centered in the park proper, federal scientists say, where it has reached its likely natural maximum and has leveled off. But in adjoining stretches of national forest, the number of grizzlies is continuing to go up by 4 percent to 7 percent a year. Their resurgence in the past 50 years is why the federal government announced in 2005 the start of proceedings to take them off the endangered or threatened species list. Dr. Logan enters the fray on the question of what grizzly bears eat, how much of it will be available in the future, and where. All that, he says, hinges on the mountain pine beetle and the whitebark pine. The tree (Pinus albicaulis) has no value as commercial timber. But gnarled and bushy whitebark pines anchor the timberline in much of the West. They hold the soil for other vegetation to get a foothold, and they trap snow, prolonging the spring runoff. They are slow-growing trees and may not even bear cones until they are a half-century old. In the late 19th century, the naturalist John Muir counted rings in a weatherbeaten example high in California’s Sierra Nevada. Its trunk was just six inches across. To his astonishment it was 426 years old. The beetle’s usual targets were once midaltitude lodgepole and ponderosa pines. But it has begun extending its range as it adapts to warming temperatures in the Rockies — two degrees since the mid-1970s. As a result, it has been killing whitebark pines at altitudes in the Rockies and the Cascades of Oregon and Washington that would have once been too cold. Beetle attacks have added to the toll taken by a disease called white pine blister rust. In the northern Rockies, the beetle infests 143,000 acres. Entire forest vistas, like that at Avalanche Ridge near Yellowstone National Park’s east gate, are expanses of dead, gray whitebarks. “We are very worried the whitebarks may be locally extirpated, if not driven extinct,” said Diana Tomback, professor of biology at the University of Colorado, Denver, and president of the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation, a nonprofit organization. One recent Forest Service study suggested that in the next century a global warming would reduce by 90 percent the acreage that has the kind of cold and high altitude climate where the trees now grow. The plight of trees may not catch the attention of most people. But the seeds of the whitebark pine, the pine nuts, feed Clark’s nutcracker birds; red squirrels, which store the nuts underground; and grizzly bears. “There is this general notion that grizzly bears are omnivores that will eat anything and do all right, but that’s not the case in Yellowstone,” says David Mattson, a wildlife biologist with the United States Geological Survey on the Northern Arizona University campus in Flagstaff. The diet of the Yellowstone grizzlies changes radically from season to season. After emerging from dens in early spring, they gorge on elk and bison calves and adults that died over the winter, or they chase wolves off their kills. Later in the spring and in early summer, tourists most often see them in rivers near Yellowstone Lake, where they go after spawning cutthroat trout. They eat roots and bulbs, too. But by late summer the bears head for remote high country. They turn to delicate fare: moths and pine nuts. In alpine meadows a grizzly can lap up 40,000 army cutworm moths a day from under rocks where the fat insects congregate during daylight hours. But mostly the bears depend on whitebark pines. A federally supported Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team says the tree’s plump seeds, among the largest of any North American pine, “are arguably the most important fattening food available to grizzly bears during late summer and fall.” Loss of the whitebarks, the task force said, would endanger the bears’ survival. The hefty bears — a male can exceed 700 pounds — do not climb the trees. They raid messy, cone-stuffed middens on the ground that red squirrels build as winter storehouses. Grizzlies in northernmost Montana, Canada and Alaska have a wide variety of berries available in the fall, and those near the coast have spawning salmon in the rivers. But when winter looms in Yellowstone, “the whitebark pines are about it” on the bear menu, Dr. Mattson says. The Wind River Pines Because of the close relationship between the pines and the bears, Dr. Logan has taken up advocacy for the bears as a means of bringing attention to the overall ecosystem in the Wind River Range in Wyoming. The range is high, broad, relatively far from the moderating effect of the Pacific Ocean and exposed to arctic blasts off the plains. They therefore are colder than nearby ranges. Dr. Logan’s computer models show them resisting a warming climate longer than other mountains and remaining a refuge for the pines and the bears. Earlier analyses that Dr. Logan conducted correctly predicted beetle movements. In the 1990s, his analyses predicted a northward invasion by mountain pine beetles from near the Washington-Canada border deep into the lodgepole forest of the British Columbia interior. Rising temperatures were revving up the beetles’ metabolisms, and he surmised that they would soon complete a full cycle of reproduction in one year. Eventually their reproduction would get in pace with the calendar well north of their usual range, a condition called adaptive seasonality. It means millions of adults emerging simultaneously from infested trees. Like an army roaring out of the trenches, they overwhelm their next round of piney prey, emitting pheromones that draw more attackers to individual trees. Forest managers say defenses — quarantines, burning and other methods — are ineffective over large areas. The result in Canada turned out as bad or worse than Dr. Logan feared. It may be the largest forest insect blight ever seen in North America, and it seems nowhere near its peak. It covers a patch running about 400 miles north-south and 150 miles across. Officials expect 80 percent of British Columbia’s mature lodgepoles to be dead by 2014. Loggers are frantically cutting lifeless trees for lumber before they rot. Funguses carried by beetles stain the wood a blotchy blue. Lumber mills promote it as stylish “denim wood.” In 2002, high winds carried the beetles through the Rockies and into the Alberta plain. They appear poised to sweep east to the Atlantic through Canada’s jackpine boreal forest. In 2001, Dr. Logan set up an observing station at a broad stand of whitebark pines at the timberline at Railroad Ridge in the White Cloud Mountains of Idaho. He expected a beetle infestation, but not for a while, and planned to collect data before the insects showed. Almost immediately, in 2002 and 2003, telltale patches of “red top” trees appeared. Today virtually all the mature whitebarks there are dead. “It was the most magnificent whitebark ecosystem I’d seen,” Dr. Logan said. “It broke my heart.” New computer projections done by Dr. Logan and Jacques Régnière of the Canadian Forest Service based on recent climate and other data for the mountain West show most whitebark pine forests being wiped out as warming continues. But the Wind River Range is projected to stay cold until 2100 or so, which, if the model is right, means they could be a refuge for grizzlies forced out of areas where the trees die. The exercise produced a map on which most of the realm of the whitebarks, previously out of reach of mountain pine beetles, turns red as the computer calculates ever-warmer decades ahead. A recent trip there showed that so far, the Wind River Range is, in fact, fending off beetle attack. Dr. Logan and several environmental groups, including the Natural Resources Defense Council, argue that the Wind River Range should be included in areas in which grizzlies are protected. The government’s plan to ease Endangered Species Act protection for Yellowstone’s bears does not mean an end to local and federal conservation measures for them. A detailed plan has been put together by the Fish and Wildlife Service and the states of Montana, Idaho and Wyoming. It includes close surveillance of bears and maintenance of their population at no fewer than 500 adults, and continued full protection in a 9,300-square-mile “prime protection area” that includes and extends out from the 3,300-square-mile national park. A far larger area farther out, including the Wind River Range, is designated as suitable grizzly bear habitat but would be subject to state and local regulations. But Dr. Logan’s projections shows devastating whitebark damage from the beetles in the government’s core area for grizzly protection by the end of the century. He says that the government’s recovery area “is completely out of touch with what is actually happening.” Government biologists say the official plan can be adjusted if the whitebarks go into serious decline and the bears are not able to adopt an adequate replacement diet of roots or other late- fall food. And if the Wind River Range to the south does turn out to be the bears’ best refuge, that’s where they’ll go. “A lot of that area is wilderness already,” said Chris Servheen, grizzly bear recovery coordinator for the Fish and Wildlife Service office in Missoula, Mont. “The bears will move in there regardless of what our rules say, and the beetles don’t care what regulations we have either.” He also argued that even outside the proposed primary protection area, state authorities had “signed up” to help protect the bears. And if things turn seriously bad, he said, the government can relist the bears. Bear Activism Bear supporters are already lining up to oppose the near-certain delisting. “The federal government has a core recovery area that it says is adequate,” said Douglas Honnold, managing attorney for Earthjustice, a Montana-based group. “Jesse’s work, and his is not the only such analysis, suggests that this is flat-out wrong. The federal government has a head-in-the-sand approach.” Mr. Honnold promised a federal court challenge. Another bear supporter, Lance Craighead of the Craighead Institute in Montana, says that “the Winds may be critical. Our own work, and Jesse’s, all say the whitebark pine will last there longer than it will anywhere.” Many believe that if the delisting goes forward, bear hunting will follow, particularly in the Wind River Range. Livestock interests, as well as hunters and some back country backpackers, do not want to share the land with grizzly bears. Wyoming’s published bear management plan, set to go into effect as soon as the bears are off the federal list, declares that significant presence of grizzly bears will not be permitted in much of the range, including nowhere in roughly the southern half. One management tool, it says, is “hunter harvest.” Fremont County, which includes the Wind River Indian Reservation, has declared grizzlies “an unacceptable species” and resolved to protect its residents. In an essay Dr. Logan wrote before the trip into the Winds, he said that if it confirmed a potential bear refuge, “we can efficiently allocate protection and reconstruction strategies.” It will be costly, he wrote, but it would be “inconsolable to simply walk away from a problem that is largely our making.” During a break on the trip’s second day, high on a pass called Kirkland Ridge, Dr. Logan said: “As for active management to encourage bears here, I don’t know. That’s a policy to be developed. But look, this is clearly a special place, a special ecosystem. It is all connected, we know that, from the plains to the mountain tops.” In the end, of course, the discovery of places that will resist warming effects may only buy time. “It’s all about global warming,” Dr. Logan said. “I can’t say if the beetle will stay out of the Winds for all the next century. I don’t know how long it will take. But one thing I do know. If it keeps on warming, they’ll get nailed there too. The trees can’t move uphill, you know. They’ll run out of mountain.” What the bears will fatten for winter on then, nobody knows.