Volume 24 - No 1: Strongyloides

advertisement

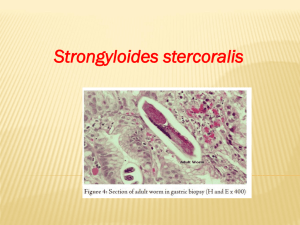

THE JOHNS HOPKINS MICROBIOLOGY NEWSLETTER Vol. 24, No. 1 Tuesday, January 4, 2005 A. Provided by Sharon Wallace, Division of Outbreak Investigation, Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. *There are no outbreaks available at this time. B. The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Department of Pathology, Information provided by, Dengfeng Cao, M.D. Patient history: This is a 62 years old black male presenting with intermittent abdominal pain for 3 months. The pain was mainly on the right side of his abdomen. In the past week, his abdominal pain became worse with diarrhea. His symptoms were not associated with any food. He did notice some bright red blood in his stool. He also had a mild fever. The findings from his abdominal CT were consistent with a pancolitis. Stool and blood were submitted for culture. His blood culture was negative. Stool culture was negative for any pathogenic bacteria. However, parasitology examination on his stool revealed rhabditiform larvae of Strongyloides stercoralis. Treatment with thiabendazole was initiated. Organism: Life cycle and Epidemiology Strongyloides stercoralis is an intestinal helminth. Strongyloides stercoralis is an unusual "parasite" in that it has both free-living and parasitic life cycles. Its life cycle is shown in the following figure (1). There are 2 types of larvae: rhabditiform larvae (noninfectious) and filariform larvae (infections). Human infection starts when the filariform larvae penetrate into the skin and then migrate through the lung and finally mature into adult worms in duodenum and jejunum. One particular feature of strongyloides stercoralis is autoinfection caused by filariform larvae (2). Strongyloides is a rare infection in the USA with the highest rates of infection found in residents of Appalachia and the southeastern states, in immigrants from endemic areas, and in those with occupational exposures (including military veterans) in endemic areas (3). Clinical manifestations: Most infected individuals are asymptomatic. The most common manifestations are mild waxing and waning gastrointestinal, cutaneous or pulmonary symptoms that persist for years or simply the development of eosinophilia in the absence of symptoms. The symptoms also depend on the stage of disease. In the early infection (larval migration), the skin shows itchy and erythematous papules. Patients may also have dry cough, throat irritation, dyspnea, wheezing and hemoptysis during the transpulmonary migration of larvae. After the larvae move to the small bowel, patients may complain abdominal pain. The cycle of autoinfection can lead to the hyperinfection syndrome by greatly increasing the parasite burden. The most common symptoms in the hyperinfection syndrome include gastrointestinal (nausea and vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain), pulmonary (cough, wheezing and hemoptysis) and systemic manifestations (fever) (3). Hyperinfection syndrome immunity usually occurs in patients with immunocompromising conditions such as lymphoma (4) and AIDS (5). Diagnosis: The diagnosis of uncomplicated strongyloidiasis is usually made by detecting rhabditiform larvae in concentrated stool or duodenal fluid specimens (3). In some patients varying degrees of eosinophilia may be the only clue and thus a strong suspicion is essential. Approximately 25 percent of infected patients have negative stool examinations (6). Besides direct detection of larvae and eggs in stool, a highly sensitive and specific ELISA serologic test has proven valuable in detecting strongyloidiasis (7). Treatment and prognosis: The treatment for strongyloidiasis is thiabendazole. Ivermectin is an alterative drug. Albendazole also has activity against strongyloidiasis. Immunocompetent patients have an excellent prognosis. In immunocomprised patients, hyperinfection syndrome may be fatal. Reference: 1. http://www.cdc.gov/dpdx 2. Lindo, JF, Robinson, RD, Terry, SI, et al. Age-prevalence and household clustering of Strongyloides stercoralis infection in Jamaica. Parasitology 1995; 110:97. 3. http://www.uptodate.com 4. Daubenton JD, Buys HA, Hartley PS: Disseminated strongyloidiasis in a child with lymphoblastic lymphoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1998; 20(3): 260-3. 5. Celedon, JC, Mathur-Wagh, U, Fox, J, et al. Systemic strongyloidiasis in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. A report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Medicine 1994; 73:256. 6. Sato, Y, Kobayashi, J, Toma, H, Shiroma, Y. Efficacy of stool examination for detection of Strongyloides infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1995; 53:248. 7. Carroll, SM, Karthigasu, KT, Grove, DI. Serodiagnosis of human strongyloidiasis by an enzymelinked immunosorbent assay. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1981; 75:706.