Development of discussion materials for the expert meeting

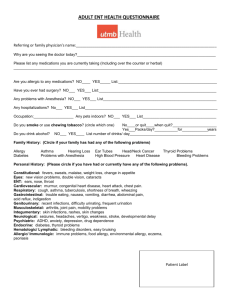

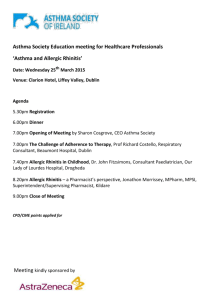

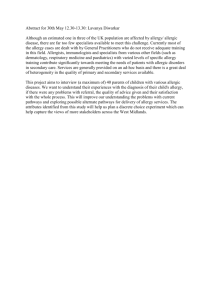

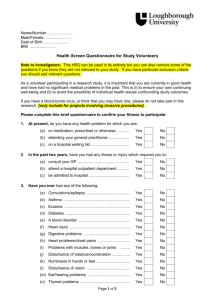

advertisement