WIPO/ACE/5/6 (in English)

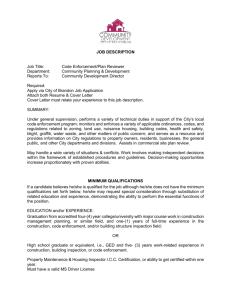

advertisement