Historical context - The University of Southern Mississippi

advertisement

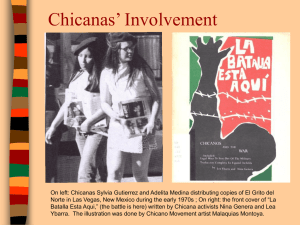

Historical-Cultural Context Ruiz (1998) stated in her book From Out of the Shadows, “[a]lthough many scholars recognize the 1960s and 1970s as the era for the modern feminist movement, they have left Chicanas out of their stories” (p. 100). History rarely speaks of the efforts and strides made by Chicana women during their feminist movement as their own cause; instead, all women are seemingly represented in the modern feminist movement. However, although Chicanas were inspired by the modern feminist movement and did take part in their efforts, they ultimately felt that their stories, their suffrage, their oppression was not the same. Instead, Chicanas felt they had suffered a double discrimination: one for being Mexican, and two for being a woman. As a result of this sentiment, Chicanas banded together and created a feminist movement of their own, the Chicana feminist movement. The Chicana feminist movement was highly influenced by both the Chicano movement and second wave feminism. The Chicano movement “called for an end to the oppression of Chicanos – discrimination, racism, poverty – goals which Chicanas supported unequivocally, but it did not propose basic changes in male-female relations or in the overall status of women” (Mirandé & Enríquez, 1979, p.234). Therefore, the Chicana feminist movement was also highly influenced by second wave feminists who sought “for women the same opportunities and privileges [that] society g[a]ve to men” (Evans, 1995, p. 2). Consequently, in order to fully understand the historical context that surrounded the article written by Mirta Vidal (1971) entitled Women: New Voice of La Raza, which addressed the Chicana feminist movement, it is also essential to discuss the two movements that highly influenced and shaped their movement: the Chicano movement and second wave feminism. 2 The Chicano Movement The Chicano Movement was a continuation of the Mexican-American Civil Rights Movement that took place in the 1940s, which sought educational, social, and political equality in the United States for Mexican-Americans (Blea, 1977). Additionally, according to Escobar (1993), the black civil rights movement of the 1950’s and 1960’s reignited the 1940’s MexicanAmerican Civil Rights efforts as they refocused public attention on the issue of racial discrimination. Moreover, the black power movement developed the concept of nationalism, which utilized racial identity as a source of pride. Chicanos borrowed this concept and “created the concept of cultural nationalism, which became the ideological underpinning for the Chicano movement” (p. 1486). According to Asunclow-Lande (1976), a large portion of the Chicano Movement focused on the rhetoric of identity and integration. Chicanos wanted to be identified as equal to their Anglo counterparts without sacrificing their pride in their language, history, culture, and race. More specifically, the Chicano movement, emulating the goals of black civil rights efforts, developed four general goals for their movement, according to Escobar: [Chicanos sought] to maintain pride in Mexican Americans’ cultural identity; to foster a political understanding that Mexican Americans were an oppressed and exploited minority group; to use the [sic] ethnic pride and the sense of exploitation to forge a political movement through which Chicanos would empower themselves; and finally, to force white society to end the discriminatory practices that restricted Chicanos’ lives. (p.1492) In order to obtain these goals, many important organizations were developed to focus on the oppression and inequality experienced by Chicanos throughout the United States. Some of 3 the most important organizations that developed were the Educational Issues Coordinating Committee, which focused on the reformation of public schools, the United Mexican American Students and the Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán, which focused on Mexican American access to higher education, the Brown Berets, who were often compared to the Black Panthers, which focused on issues of education, health care, and police brutality. Additionally, La Raza Unida party was formed, which attempted to form a third political party to address Chicano concerns (Escobar, 1993), and civil rights leader Cesar Chavez’s efforts were aimed at creating a Farm Workers Labor union, which would secure safer working conditions and higher wages for farm workers (Chicano!, 2000). These organizations worked together to “influence the social systems that ha[d] perpetuated social injustices” (Aguirre, 1972, p. 2). Demonstrations to pursue the above mentioned goals ranged from quiet protest to violent demonstrations. Regardless, all efforts sought to free the Chicano from a discriminating society, and to recreate a Chicano identity that was free from the margins of society, and treated equally in all spheres of life. Second Wave Feminism As the ‘first wave’ of the feminist movement “succeeded in achieving a significant victory – that of enfranchising women within the political and legal system” (Whelehan, 1995, p. 4), which ultimately secured women the right to vote, the ‘second wave’ of the feminist movement sought “for women the same opportunities and privileges [that] society g[a]ve to men” (Evans, 1995, p. 2). In essence, ‘second wave’ feminist women “believed that men and women are equal and [that women] should have equal respect and opportunities in all spheres of life – personal, social, work, and public” (Wood, 2008, p. 323). Additionally, second wave feminists evaluated the effects of a patriarchal organization, which inheritably embedded 4 inequality into their private lives. Due to this inequality, second wave feminists fought to incorporate change in this sphere of their lives, as well (Whelehan, 1995). According to Evans (1995), early second-wave feminism took on two forms of equality. The first was more liberal, and began with the Presidential Commission of 1960, and The Feminine Mystique. The second form was more radical and emerged from the 1960’s New Left, and the movement for black civil rights. Regardless, it is noted that both sought for an element of sameness, which asserted that “men and women are and could be the same, and equal or capable of being equal once stereotypes [of women were] changed or barriers [were] removed” (p. 14). In the late 1960’s, according to MacLean (2006), due to the increasing support of the women’s liberation, “the ranks of women activist surged, their supporters multiplied many times over, and the pace of the reform accelerated” (p. 19). As a result of the increasing support, many women’s groups and political forces began to form as they worked actively towards establishing change. Among the organizations formed was the National Women’s Coordinating Committee, which was known for encompassing all vying feminist positions and the Women’s Aid Federation. Both organizations developed platforms that included the following issues: equal pay, equal education and job opportunities, birth control and abortion, and childcare (Whelehan, 1995). A few years later, MacLean (2006) notes that women “won protection from employment discrimination, inclusion in affirmative action, abortion law reform, greater representation in media, equal school access to athletics, congressional passage of an Equal Rights Amendment, and much more” (p. 19). Second wave feminism was enjoying its share of success, and continued to make advances as far into the late 1980’s and early 1990s (Whelehan, 1995). 5 Chicana Feminist Movement Initially, Chicana women were inspired by the efforts of white feminists. Chicanas also wanted to fight against gender inequality and the domineering patriarchal system; however, they soon realized that they must create their own identity as their Anglo counterparts refused to address racial and class inequalities as part of their movement. As a result of this refusal, Chicanas began to see the movement as a White middle-class movement only. Being that Chicanas saw themselves as Chicanos first, and women second, they separated from the established feminist movement and created their own, which is now known as the Chicana Feminist Movement (Exploring the Chicana, n.d.). The Chicana Feminist Movement, also referred to as Xicanism, served as a middle ground between the Chicano Movement and the Women’s Liberation Movement. The Women’s Liberation Movement sought to establish for women a position of equality in a male driven world. The Chicano movement sought educational, social, and political equality in the United States for Mexican-Americans (Blea, 1977). The Chicana Feminist Movement sought to do both. Chicana feminist wanted to establish social, cultural, and political identities for themselves in America (Blea, 1977), but also sought to establish an identity for themselves in their own culture, in their own household. Flores (1996) stated that the Chicana feminist often felt alienated and isolated, and longed for a space and home in which they belonged. In 1969, the Chicana Feminist Movement began to take form as a result of the 1969 Chicano Youth Liberation Conference, which was held in Denver, CO and was sponsored by the Crusade for Justice. In attendance were more than 1500 young men and women (Ruiz, 1998). It was at this conference that Chicano issues first gained a national platform. Moreover, it was at this conference that women began to participate in male-dominated dialogues. Additionally, this 6 conference provided a venue for women to rally together to address feminist concerns that consisted of both racism and sexism. As a result of this conference, it is noted that women went back to their communities as activists; thus, signifying the beginning of the Chicana Feminist Movement (Exploring the Chicana, n.d.). By 1971, in Houston, Texas, at La Conferencia de Mujeres Por La Raza (First National Chicana Conference), Chicana women were speaking out with a distinct feminist platform. Issues included on the platform included: “free legal abortions and birth control in the Chicano community be provided and controlled by Chicanas, higher education, for acknowledgement of the Catholic Church as an instrument of oppression, for companionate equalitarian marriage, and for child care arrangements to ensure women’s involvement in the movement” (Ruiz, 1998, p. 108). Being that these issues, as well as the movement, were controversial in nature, it was evident that the Chicana Feminist Movement was highly scrutinized. The Chicana cause needed help. In order to help strengthen and advance the Chicana cause, it was necessary for someone to help legitimize the claims of the movement. This necessity for legitimacy is what prompted Vidal to write about the cause in her article Women: New Voice of La Raza. However, due to Vidal’s professional affiliations and personal allegiances to certain political ideologies, her article could have perhaps done very little for those who either disagreed or dismissed the cause. Rhetor/Author According to Studer (2004), Vidal was born in Argentina in 1949 and migrated to the United States as a youth. In the late 1960s, Vidal joined the Socialist Workers Party, which marked the beginning of a lifelong pursuit to educate individuals on socialism, and later communism. 7 Studer asserts that Vidal’s experiences regarding the following movements influenced her to join the communist movement: She was a part of a generation that was deeply affected by the rising tide of revolutionary struggles throughout the Americas in the wake of the 1959 Cuban Victory, the depth and tenacity of the national liberation struggle of the Vietnamese people, and the mass proletarian movement for Black rights in the United States that gave impetus to struggles by Chicanos and other oppressed nationalities, as well as to the movement for women’s emancipation exploding onto the political scene at the time. (para. 2) Vidal’s passion to educate individuals regarding communism lead her to join the following organizations: United States Committee for Justice to Latin American Political Prisoners, Young Socialist Alliance where she served as national director of the Chicano and Latino Work, and the Socialist Workers Party. According to Studer, Vidal was attracted to these organization’s political perspectives of the revolutionary working-class, therefore dedicating her life to establishing and advancing their missions. Professionally, Vidal held many writing assignments with various magazines rooted in socialist and communist ideologies. Initially, Vidal served on the staff of the Militant where she wrote on political developments in the United States and Latin America. Additionally, in the Militant, Vidal wrote a regular column on the Chicano struggle entitled La Raza en acción. Additionally, in 1971, Pathfinder published a pamphlet by Vidal entitled Chicano Liberation and Revolutionary Youth. Moreover, Pathfinder also published her pamphlet entitled Chicanas Speak Out: New Voice of La Raza. In 1973, Vidal held a writing assignment with Socialist Workers Party leader Ed Shaw. This assignment took them both to Argentina to cover the presidential campaigns. In 1977, 8 Vidal became the first editor of Perspectiva Mundial, the Militant’s Spanish-language sister magazine, where she helped to establish high standards for translation and reporting. Studer (2004) states that Vidal “developed her abilities as an organizer and learned the importance of accurate translation, the bedrock for learning and sharing political experiences and views among equals” (p. 6). Ultimately, Vidal’s chronic health problems led her to drop her memberships in the Socialist Workers Party in the 1980’s. However, as much as her health would allow, Vidal continued to support and participate in the party’s political campaigns until her death in 2004. Because of Vidal’s background, it is evident why she chose to cover the Chicana Feminist Movement and write Women: New Voice of La Raza. Being a member of both the communist and socialist movements, Vidal was able to recognize similar plights and struggles inherent in the Chicana Feminist Movement from others she covered throughout her career. Additionally, because of Vidal’s assignments as a writer and editor of various socialist and communist magazines, her name had been well established, which brought a highly level of credibility to what she wrote, therefore establishing the Chicana movement as a valid cause among readers who readily accepted Vidal’s opinions as the truth. However, the very things that established Vidal as a credible writer among the socialist and communist communities could possibly have been her downfall with the rest of the world. Communism and socialism were supported only by a loyal few in the United States. Others feared the implications that these governmental ideologies would bring. Therefore, for Vidal to be known as a socialist and communist supporter, her credibility and the worth of her writings could have possibly plummeted among those resistant to socialism and communism. Additionally, since Vidal’s name was now attached to The Chicana movement, the ability to 9 reach other individuals and persuade them to support this cause could have become problematic for now the Chicana cause could have been interpreted as left wing or an extension of a socialist or communistic movement. Audience As established through the historical discussion, both the modern feminist movement and the Chicano movement contained a level of controversy. For both movements, clear supporters existed; however, there were also many individuals who resisted the platforms that both organizations established. Therefore, in order to advance the cause of the Chicana feminist movement, the rhetor, Vidal, was faced with the task of targeting three parts of society. First, Vidal was tasked with reaching avid supporters in order to encourage them to continue their allegiance. Secondly, Vidal was tasked with reaching those individuals who opposed the Chicana cause. Lastly, Vidal was tasked with reaching the segment of the audience that had no opinion regarding the cause hoping to persuade them to join the ranks of the supporters. The initial empirical audience of Vidal’s article Women: The New Voice of La Raza was made up of readers of the International Socialist Review (ISR). From 1956-1975, the ISR was a Trotskyite publication produced by the Socialist Worker Party, and also functioned as a supplement to the organization’s weekly newspaper, The Militant. According to the International Socialist Organization (ISO) website, the ISR is a publication that many of their members subscribe to. Additionally, the ISO website indicates that the ISR is a magazine that has a political allegiance to socialism and Marxism (ISO, n.d.). Therefore, although demographical data is not available regarding subscribers, inferences can be made based on the magazine’s political ideologies regarding the characteristics of ISR subscribers. By making these inferences, it is obvious that the majority of the empirical audience reached by Vidal were 10 socialist and Marxists supporters. Therefore, by publishing in the ISR, Vidal was able to reach the part of society that may have already been accepting of the Chicana cause, and was also able to reach readers that had no previous opinion regarding the Chicana feminist movement. Being that Vidal was a well-known and well-received socialist voice, it was probably easy for her to persuade these subscribers that the Chicana cause was worthy of their support, or if they were already supporters, she was able to strengthen their opinions regarding the cause. A second target audience that Vidal was trying to reach through her article was those that opposed the Chicana feminist movement. However, although it would have been ideal for Vidal to reach this audience, the possibility of doing so was rare being that the article was published in a magazine that more than likely conflicted with their views; therefore, they were not likely subscribers to the ISR. Therefore, opponents, more than likely, never viewed the article. A third target audience that Vidal was trying to reach consisted of those individuals with no opinion. However, a similar problem existed. Unless those individuals read the ISR, it was not likely that they would be exposed to the article; therefore, they would continue with no opinion or an opinion would be formed based on alternative data and information offered by an alternate source. Ultimately, the analysis of the audience indicates that Vidal may have been preaching to the choir. Therefore, instead of gaining supporters and converting opponents, Vidal instead was limited to strengthening the allegiance of current supporters. Although this was an important in retaining the current state of the movement, it is possible that it did not strengthen nor advance the Chicana feminist movement. Possible stagnancy could have stemmed from competing persuasive forces that existed. Competing Persuasive Forces 11 Competing persuasive forces that worked contradictory to Vidal’s goal, to legitimize the Chicana cause and gain supporters, can be seen both internally and externally. Internally, the Chicana cause met resistance from inside the Chicano culture. Externally, the Chicana cause met resistance from the media, and by opponents outside of the culture that disagreed with the movements as they were seen as part of or highly influenced by the Chicano movement and modern feminist movement. Internally, many Chicana women were discouraged from joining the Chicana feminist movement as they were told that they were dividing the Chicano movement and were being selfish in putting themselves before their families. Additionally, many Chicana women were discouraged to join the movement by other Chicana women as they were told that “there was no need for a separate movement [because the movement was] Anglo inspired and could only work to split Chicanos” (Mirandé & Enríquez, 1979, p. 237). Moreover, Chicano men also worked internally to discourage the joining of the movement. Many Chicano men accused Chicana feminists as being bra burners or man haters and agabachadas (“Anglocized”) (1979). Externally, the Chicana movement had to survive its negative portrayal in the media. In the media, the Chicana movement may not have been individually covered; however, its connection to the Chicano movement and modern feminist movement made it a logical extension of the Black Civil Rights movement, which was highly resisted among opponents and skeptics. Additionally, media also consistently portrayed feminist as man haters. As a result of the internal and external persuasive forces, Vidal’s goal to legitimize the Chicana movement was a difficult one. Additionally, being that Vidal was only able to express her views via a socialist magazine, opponents and undecided individuals were more likely held captive to the media portrayal of the Chicana cause than to those provided by Vidal. 12 Review of Relevant Literature Just as the Chicana movement encountered problems trying to establish an identity of its own, the same has occurred regarding the scholarship devoted by critics to exploring the rhetoric surrounding the Chicana movement. Aside from a few articles that address Chicana’s rhetoric independently (e.g., Enoch, 2005), most is seemingly represented in the analysis surrounding both the Chicano movement and second wave feminist rhetoric. Rhetoric of the Chicano Movement Although more literature has been published regarding the Chicano movement than the Chicana feminist movement, it is still sparse. Many of the articles that do exist analyze the rhetoric produced by Cesar Chavez and Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales. Both men have been said to have contributed significantly to the Chicano movement as leaders; therefore, making their oration worthy of study. Chavez, founder and president of the United Farm Workers, has been praised as one of the twentieth century’s greatest orators. Due to his ability to persuade many labor workers to unite and demand change, his strategies are often analyzed (e.g., Hammerback & Jensen, 1980, Hammerback & Jensen, 1994, Jensen, Burkholder, & Hammerback, 2003, and Zompetti, 2006,). Similarly, author of Yo Soy Joaquin, Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, was also known to have significantly contributed to the Chicano movement through the use of his rhetoric, which also united La Raza. Jensen and Hammerback (1982) examined Gonzales’ public addresses as he sought to improve the lives of Chicanos. Analysis found that Gonzales’ substantive themes, primary audience, and rhetorical techniques separated him from other, less influential, Chicano leaders. 13 More generally speaking, Powers (1973) sought to establish presuppositions pertinent to the understanding of the Chicano movement. Powers, recognizing that the Chicano movement was significant in its persuasive efforts to unite, established five axioms that were inherent in unification rhetoric established in the Chicano movement: the feeling of oppression, La Raza, the robbery of conquered people, Huelga, and Aztlán. Additionally, Delgado (1995) surveyed Chicano movement rhetoric and argued that the unification of Chicanos was established through key documents that created and rooted their political ideologies as presented in El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán and El Plan de Santa Barbara. Although the above literature addresses unification rhetoric that appears to have surrounded the Chicano movement, and that unification was also a key factor in the Chicana movement, it does not address the rhetoric that surrounded the Chicana movement regarding their rights as women. Therefore, I will turn to a review of second wave feminist rhetoric to address this portion of their movement. Rhetoric of Second Wave Feminism Dow (2005) asserts that in rhetorical studies, the second wave has received less attention than that received by the first wave. She attributes this fact to the notion that the first wave fit so well into the traditional public address paradigm; whereas, the second wave does not. Due to this fact, Dow notes that second wave is a “messier movement, and the rhetorical scholarship devoted to it is smaller and less cohesive” (p. 90). Additionally, Dow notes that the “fragmentation and general absence of second wave scholarship in rhetorical studies reflects the elusive nature of the movement itself” (p. 90). However, some scholars have attempted to “incorporate women into the rhetorical tradition and to develop critical perspectives and theory 14 better suited to understand women’s discourse during the second wave of feminism” (Campbell, 2001, p. 9). According to Campbell (2001), initial efforts were established through the recovery of women’s texts, which provided the material for anthologies of speeches by women (e.g., Anderson, 1984; Kennedy & O’Shields, 1983), social-movement analysis of women’s rights (e.g., Campbell, 1989), and documents that evaluate women’s petitioning activities (University of Wisconsin, 1997). Furthermore, Campbell (2005) also noted that some scholars contributed their time to establishing critical perspectives and theories to enlarge the understanding of women’s rhetoric. As an example, Campbell discusses how Lynne Derbyshire’s (University of Maryland, 1997) dissertation explored the “prior discourse that created an alternative subject position for women that allowed the constitutive rhetoric of the Seneca Falls Convention to succeed” (p.10). Furthermore she noted how Browne (2000) analyzed women’s discourse to show how an identity or signature was symbolically channeled into moral reform. Aside from critical perspectives and theories, Campbell introduces a wealth of literature published in articles that deal with second wave feminism: Carol Blair alone has written incisive critiques of traditional rhetorical theory. Carol Jablonski has written about the efforts of Catholic women; Suzanne Daughton is the new editor of Women’s Studies in Communication; she has written on Angelina Grimké and generally on women’s political rhetoric. Helen Shark has authored and edited works on the construction of gender . . . Celeste M. Condit has published books on abortion rhetoric . . . Mari Boor Tonn has written extensively on the rhetoric of women in the labor movement. (p. 11) 15 Although providing a list of published journal articles, Campbell (2005) again notes that although a handful of articles can be found regarding women’s rhetoric from the second wave of feminism, “feminist rhetorical theory is in its infancy in communication studies” (p. 11). This infancy can be exhibited through the lack of scholarship devoted to rhetoric surrounding the Chicana feminist movement. Although, as time passes, efforts are being made to include the rhetoric of subgroups, such as Blacks and Chicanas as established in Roth (2003) book entitled Separate Roads to Feminism: Black, Chicana, and White Feminist Movements in America’s Second Wave. Conclusion Although in rhetorical studies Chicana movement rhetoric is sparse, one attempts to understand its context through the scholarship devoted to both the Chicano and second wave feminist movements. However, it remains equally important for scholars to devote their time and efforts to studying the rhetoric surrounding the Chicana feminist movement, for it is through this scholarship that the Chicana feminist rhetoric can gain its own identity and begin to stand on its own. 16 Works Cited Aguirre, L. (1972). The Meaning of the Chicano Movement. In M. Mangold (Ed.), La Causa Chicana: The Movement for Justice (pp.1-5). New York: Family Service Association of America. Asunclow-Lande, N. (1976). Chicano Communication: Rhetoric of Identity and Integration. Association for Communication Administration Bulletin, Retrieved January 24, 2009, From Communication & Mass Media Complete database. Blea, I. I. (1977). U.S. Chicanas and Latinas within a global context: Women of color at the Fourth Women’s Conference. Connecticut: Praeger. Campbell, K. (2001). Rhetorical Feminism. Rhetorical Review, 20(1/2), 9. Retrieved March 11, 2009, from Professional Development Collections database. Chicana Feminist Theory & Chicana Feminist Issues. (n.d.). Retrieved January 23, 2009, from the University of Michigan: http://www.umich.edu//~ac213/student_projects07/latfem/ lat/fem/whatisit.html Chicano! History of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement. (2000). Retrieved March 6, 2009, from the Albany University: http://albany.edu/jmmh/vol3/chicano/chicano.htm Delgado, F. (1995). Chicano movement rhetoric: An ideographic interpretation. Communication Quarterly, 43(4), 446-455. Retrieved March 8, 2009, from Communication & Mass Media Complete database. Dow, B. (2005). Review essay: Reading the second wave. Quarterly Speech of Journal, 91(1), 89-107, Retrieved March 8, 2009, from Communication & Mass Media Complete database. Enoch, J. (2005). Survival stories: Feminist historiographic approaches to Chicana rhetorics of 17 Sterilization abuse. RSQ: Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 35(3), 5-30, Retrieved March 8, 2009, from Communication & Mass Media Complete database. Evans, J. (1995). Feminist Theory Today: An Introduction to Second-Wave Feminism. London: SAGE Publications. Exploring the Chicana Feminist Movement. (n.d.). Retrieved January 23, 2009, from the University of Michigan: http://unich.edu//~ac213/student_project05/cf/issuestheory.html Flores, L. (1996). Creating discursive space through a rhetoric of difference. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 82(2), 142. Retrieved January 24, 2009, from Communication & Mass Media Complete database. Hammerback, J. & Jensen, R. (1980). The rhetorical worlds of Cesar Chavez and Reies Tijerina. Western Journal of Speech Communication: WJSC, 44(3), 166-176. Retrieved March 8, 2009, from Communication & Mass Media Complete database. Hammerback, J., & Jensen, R. (1994). Ethnic heritage as rhetorical legacy: The plan of Delano. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 80(1), 53. Retrieved March 8, 2009, from Communication & Mass Media Complete database. International Socialist Organization. (n.d.). What we stand for. Retrieved March 8, 2009, from http://www.internationalsocialist.org/what_we_stand_for.html Jensen, R. J., Burkholder, T. R., & Hammerback, J.C. (2003). Martyrs for a just cause: The eulogies of Cesar Chavez. Western Journal of Communication, 67(4), 335-356. Jensen, R. J., & Hammerback, J. (1982). “No revolutions without poets”: The rhetoric of Rodolfo“Corky” Gonzales. Western Journal of Speech Communication, 46(1), 72-91. MacLean, N. (2006). Gender is powerful: The long reach of feminism. Magazine of History, 20(5), 19-23. Retrieved March 8, 2009, from America: History & Life Database. Mirandé, A., & Enríquez, E. (1979). La Chicana. Chicago: The University of Chicano Press. 18 Powers, L. D. (1973). Chicano rhetoric: Some basic concepts. Southern Speech Communication Journal, 3(4), 340-346. Ruiz, V. L. (1998). From Out of the Shadows. New York: Oxford University Press. Studer, J. (2004). Mirta Vidal, Lifelong Socialist. Retrieved January 26, 2009, from The Militant: http://themilitant.com/2004/6803/680353.html Vidal, M. (1971). Women: New Voice of La Raza. Retrieved January 22, 2009, from Duke University: Special Collections Library. Web site: http://scriptorium.lib.duke.edu/wlm/chicana/ Whelehan, I. (1995). Modern Feminist Thought: From Second Wave to ‘Post Feminism’. New York: New York University Press. Wood, J. T. (2008) Critical Feminist Theory: Giving Voice and Visibility to Women’s Experiences in Interpersonal Communication. In L. Baxter & D. Braithwaithe (Ed.), Engaging Theories in Interpersonal Communication: Multiple Perspectives (pp. 323-334). California: Sage Publications, Inc. Zompetti, J. (2006). Cesar Chavez’s rhetorical use of religious symbols. Journal of Communication & Religion, 29(2), 262-284. Retrieved March 8, 2009, from Communication & Mass Media Complete database.