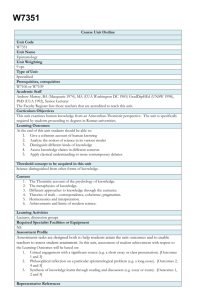

Epistemology and human sciences

advertisement

Andrzej Kapusta (UMCS) I'm currently a lecturer (adiunkt) in the Philosophy and Sociology Faculty of the Marie CurieSklodowska University in Lublin, Poland. My research interests lie in the area of philosophy of mind, philosophy of psychiatry, philosophy of human sciences. My main current project is the attempt to give a model for explanation of disturbances of mind in psychopathology. I’m the author of the book: Filozofia ekstremalna. Wokół myśli krytycznej Michela Foucaulta (2002) Epistemology and human sciences Abstract: In this paper I would like to make a distinction between some characteristic features of human activity which not only challenge the possibility of being explained (reduced) in terms of cause and effect relationship, or by universal regularities, but which assign an element of interpretation and understanding to every human activity. My aim is to demonstrate that it is not the understanding that is submitted to scientific explanation but that every scientific explanation contains the component of interpretation and is evaluated from the viewpoint of our everyday, pre-reflexive being in the world and commonly (often implicite) accepted contexts and assumptions. In other words, we have to constantly refer to the existing background - a network of unspecifiable beliefs and practices. I would like to point out, after Charles Taylor and Hubert Dreyfus, that the responsible epistemology of the humanities must overcome a series of assumptions of modern and contemporary cognitive theory which appeared to be surprisingly congruent with the classic thinking paradigm concerning natural sciences. Last but not least, I would like to prove, relying upon involved epistemology or hermeneutic proto-epistemology, the possibility of mutual symbiotic relationship between the perspective of natural sciences and humanities. Key words: epistemology, human sciences, hermeneutics, antirepresentationalism, Charles Taylor In this paper I would like to make a distinction between some characteristic features of human activity which not only challenge the possibility of being explained (reduced) in terms of cause and effect relationship, or by universal regularities, but which assign an element of interpretation and understanding to every human activity. My aim is to demonstrate that it is not the understanding that is submitted to scientific explanation but that every scientific explanation contains the component of interpretation and is evaluated from the viewpoint of our every-day, pre-reflexive being in the world and commonly (often implicite) accepted contexts and assumptions. In other words, we have to constantly refer to the existing background - a network of unspecifiable beliefs and practices. I would like to point out, after Charles Taylor and Hubert Dreyfus, that the responsible epistemology of the humanities must overcome a series of assumptions of modern and contemporary cognitive theory which appeared to be surprisingly congruent with the classic thinking paradigm concerning natural sciences. Last but not least, I would like to prove, relying upon involved epistemology or hermeneutic proto-epistemology, the possibility of mutual symbiotic relationship between the perspective of natural sciences and humanities. The dispute about the research method in the humanities For contemporary philosophy, the development of natural sciences poses a sizeable challenge. Not only because their progress has dramatically changed the image of the world, but also because our thinking has been dominated by the slogans of reliable and justified methods and research objectivism based on science. The efficiency of natural sciences has been rested on a systematic investigation of the reality by disregarding our individual, subjective convictions and popular ideas of the world. Consequently, it has become attainable to harness nature by its (proper) classification, explanation of its mechanisms and the likelihood of predicting its events. Nevertheless, a historically substantiated, gradual process of departing from nature revealed the actual lack of such detachment and a considerable dose of commitment to the insight into the social phenomena. Therefore, besides the endeavours to incorporate the socio-cultural issues into the research methods of natural sciences, at the turn of the 19th century, under the banner of the unity of sciences, there emerged a number of ideas to create a method alternative to the humanities (in particular in German philosophy). Humanistic researchers striving to strengthen this characteristic method found support in a priori universal values (Heinrich Rickert), or in the world of objective spirit and life (Wilhelm Dilthey), or, as in Max Weber, in the instrumental rationalism of entities (or social groups). After all, the attempt to define the method of humanistic research gave rise to hermeneutic concepts and the criticism of the prospect of creating a scientific method for the humanities and the infeasibility to fully and formally reveal the conditions of accurate interpretation. It is done by revealing pre-cognitive aspects of human experience. It comprises, (1) ontological structure of human being (Dasein) for which understanding is something already existing albeit never fully explicable in terms of cognition or conceptual knowledge). (2) Also the character of the dynamics of the social world is pointed out where the senses sneaking across the language or evolving historically enable intersubjective relation to the world. Martin Heidegger, and later Georg Gadamer, retain some facets of Dilthey’s thinking when underlining the sense and time of human actions, yet they stress human finiteness and limitations of the insight into the possible preconditions of intentional attitude and made the understanding and interpretation process incomplete and, to some extent, nonobjective (non-algorithmicized and unfinished). Following “the spirit” of Kant’s research on the conditions of the capacity of knowledge, a question arises of the condition of intentionality (of understanding human works and behaviours). From a hermeneutic viewpoint, it is not possible to determine the formal conditions of interpretation. Heidegger points to pre-theoretical and pre-(conceptual) understanding of the world and oneself which is never fully uttered (against Dilthey’s assumptions, or Husserl’s aspirations). Hence, the natural sciences reach out to the world of human practice and in this respect constitute a secondary and depleted relationship with the world. The original positivist unity of science was finally replaced by the ubiquity (all the way down) of interpretation, i.e. hermeneutic universalism.1 Epistemology and antirepresentationalism Before we discuss the reservations voiced about this hermeneutic approach, in particular the issue of relativism and scepticism, we will prove that the phenomenological and hermeneutic perspective has some instruments of criticism of contemporary epistemology and reveals how deeply coherent it is with the image of the world imposed by the methods of natural sciences. Apart from the well-known disapproval of Richard Rorty, also Charles Taylor, or Hubert Dreyfus, criticise epistemology by showing its modern and contemporary features. These are: a) The attitude of uninvolved methodologism and acontextualism; b) I/O: inner/outer distinction and associated mediational view, or representationalist view; c) Epistemological foundationalism. The above elements of a classical cognitive theory are best visible in Cartesian philosophy. As the father of contemporary epistemology, he was convinced that only (a) the ordering and control of internal ideas is a precondition for acquiring positive knowledge. If Plato and Aristotle believed that they were able to grasp the cosmic order of the world, its Hermeneutics is not only struggling to overcome naive positivism but also K. Popper’s rational reconstructionism as well as social constructivism of the sociology of knowledge. 1 forms and ideas, disenchanted, mechanical world of Descartes finds the spirit in (the reflexive) subject and its (b) internalized ideas/representations. As in later Locke’s findings, ideas are not only the traces that the material world leaves behind in the human mind but also the mirrors of this world and provide the only access to it. The precondition of knowledge is not only the existence of representations but also (a) the separation of the subject from the world and life. The Cartesian subject’s objective is to discover that it is not the psychophysical unity, as we believe relying on everyday experience, but must become aware of the separation of the world of thought from the mechanisms of the body.2 Despite the broad criticism of Cartesian approach in the contemporary epistemology, Charles Taylor shows how many present-day researchers are still the devotees of the epistemological model. The inner/outer distinction (b) (I/O) in Descartes was the effect of taken account of the disenchanted world of post-Galileo science which affects us in the form of causal natural laws and reaches the ultimate point, that is, the input of our mind. In its materialistic (naturalistic) version, this system of thinking is still maintained and the input this time gets inside the brain machinery, whose purpose is to create, by means of (a) data processing in line with certain algorithm, (b) the representations of its surroundings. Another interesting element of Cartesian approach, which is preserved in the present-day epistemology, is (c) foundtionalism, i.e. the acceptance of the necessity of peeling back all the layers of inference and interpretation and reaching some original brute Facts. Thus, we face here the trust in the method which aims to develop a reliable body of knowledge by finding interpretation-free elements and creating the building material by suitable method of our knowledge of the world. This strategy perfectly fits today’s cognitive models of mind which are set in disenchanted nature where the mind, like a machine, processes simple elements of data. It is worth noting that this reference to simple and neutral elements represents a crucial facet of the criticism of hermeneutic philosophy.3 The model of representational epistemology brought about lots of trouble to its followers, in particular the threat of antirealism and scepticism. For if we can access only immanent ideas (representations), do we have the right to put confidence in our belief in external independent objects? A number of dualisms that emerge in contemporary epistemology are strongly related to the epistemological mediational approach. Let us take the problem discussed by John McDowell of reconciliation of the element of activity 2 Cf. G. Ryle, The Concept of Mind, University of Chicago Press 1949. The criticism of epistemological foundationalism was not only the province of the continental philosophy; likewise, late Wittgenstein displays some elements of the hermeneutical perspective. 3 (spontaneity) of cognition and receptivity (passivity), as well as the realm of reasons with the realm of causes.4 The above-said problems and dualisms vanish when epistemology takes the engaged/involved shape which, as pointed out by Heidegger, Taylor, or Dreyfus, begins with the pre-conceptual understanding. Understanding is possible owing to the engaged agent defining the meaning (significance) of a thing following their desires, actions and goals. The significances are possible because of the combination of spontaneity and reception, constrains and striving. Adopting the practical approach to the world as the original one, implies a sort of antifoundationalism pointing to the concealed and never fully articulated components of our life and stance not searching for simple and non-demanding interpretation of cognitive elements (some brute Facts). Taylor finds the traits of mediationism even in the formal opponents of representationism and foundationalism, such as Donald Davidson or Richard Rorty, when they stress the impossibility to reach beyond beliefs and language-based image of the world (like the expressions: “we can’t get outside”). This is how they concur to coherentism, “what distinguishes a coherence theory - says Davidson- is simply the claim that nothing can count as a reason for holding a belief except another belief”5. Hermeneutics and the humanities A philosopher who exerted considerable influence over the development of hermeneutics was Hans-Georg Gadamer with his theory of universal hermeneutics revealing the ubiquity of understanding and interpretation in every human activity, also that of natural science. This is how he defined his attitude towards the previous scientific and theoretical self-awareness. In the positivist scientific and research interpretation we are faced with a onesided focus on an object and its manipulation, and finally as a goal, the absolute intellectual control over the object even if the original notions were not perfect. On the other hand, in the social sciences: a) The relationship with the examined object is bilateral. The social and cultural reality (or specific person) can answer our questions; 4 J. McDowell, Mind and World, Harvard University Press 1994. D. Davidson, A Coherence Theory of Truth and Knowledge [in:] Truth and Interpretation. Perspectives on the Philosophy of Donald Davidson, ed. E. LePore, Blackwell, Oxford 1986, p. 310 (author’s emphasis (A.K.). Worth mentioning is the criticism of McDowell and an interesting concept of Jana Srzednicki. 5 b) Understanding is contingent upon who takes the examination (party-dependent), and the object itself is subject to change during the check; c) The aim of interpretation is common action (and not manipulation of the object); this should results in the change of one’s perspective (horizon) and redefinition of one’s goals (and not only means). The dissimilarity of this approach to cognition and its positivist interpretation is best shown in Gadamer’s understanding of the notion of experience, as unrepeatable and open and escaping the framework of a scientific theory: “For experience itself can never be science. Experience strands in an ineluctable opposition to knowledge and the kind of instruction that follows from general theoretical or technical knowledge”6. The impossibility to anchor a hermeneutic research to methodology follows from an unavoidable trap of tradition and implicite accepted cultural assumptions, or even carnal habits which influence the perception (interpretation) of a specific phenomenon. Gadamer uses the term, prejudice, as a positive entanglement with certain assumptions. It is the prejudice that comprises the implicite assumed, or shared, condition of general cognition, the condition of entering the hermeneutic circle of interpretation. Among the essential assumptions of the hermeneutic approach, the following are worth noting: a) Hermeneutic attitude is a practical knowledge based on understanding of meaning; b) Its aim is to understand what something may mean or signify c) Hermeneutic hypothesis cannot be verified or falsified, but only clarified d) Validity of hermeneutic approach is assessed by reference to clarity of sense and depends on internal evidence (insight) of the researcher which cannot be generated by the gathering of data or logical reasoning e) Interpretations are not only assessed in relation to their clarity of meaning, but by their fruitfulness, possibility for opening new ways of understanding. The philosophy of universal hermeneutics is constantly charged with relativism and scepticism (even antirealism). Thus, if no interpretation is ultimate and always limited to the initial limits, it is easy to deduce its arbitrariness and correspondence to the alternative 6 Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method. 2nd rev. edition. trans. J. Weinsheimer and D.G.Marshall. New York: Crossroad, 1989, p. 355. approaches to this phenomenon. This, in turn, is related to the charge of impossibility to reach the reality itself and clinging to one’s own images and projections. The arguments against relativism and scepticism point to the fact that the situation of human finiteness (time and perspectivism) is a precondition of cognition and not only the limiting or determining factor.7 The features of the hermeneutic interpretation embrace, among others, the following views: a) Interpretation is circular, indeterminate and perspectival (hermeneutic circle) b) Interpretation appears against a “background” network of unspecifiable beliefs and practices (background thesis) c) The background is a condition for the possibility of interpretation which rather enables than limits (enabling condition) d) The conditions of possibility of interpretation are neutral with regard to the warrants of knowledge claims (neutrality thesis). Enabling condition (c) and neutrality theses (d) are the most controversial; therefore it is necessary to stress the fact that the shared background constraints are not strong enough to act as fixed limits reducing the option of distancing towards the interpreted object and the opportunity to accept the best achievable interpretation at a particular moment. This is where a strong dialogue element of hermeneutics comes into play and the necessity to recognize the existence of an active, involved subject being able to stay clear of the factors which originally impose a specific view of oneself and others. This active of role of the engaged agent (as distinct from distant or passive subject) reveals the specificity of the humanistic discourse which cannot overlook the fact that cognitive functions comprise but a single aspect of begin a human. Another crucial element is the driver towards self-explication and even autocreation. The influences and conditions of the criticized epistemology are seen by Taylor in the processes of contemporary societies in the form of instrumental (methodological) support of the reason and social individualism. Some researchers treat the development of classical epistemology as another attempt to impose order and muzzle any forms of human autocreativity. This anthropological element is observable also in Gadamer when, after Hegel, he speaks of Bildung, a humanistic ethos of self-building. 7 Cf. The Interpretive Turn: Philosophy, Science, Culture by Bohman, James; Hiley, David R.; Shusterman, Richard. Ithaca, New York, USA: Cornell Univ Pr, 1992; W. M. Cooper Is Medicine Hermeneutics all the way down? “Theoretical Medicine” 1994, 15 pp. 149-180. Hermeneutics as proto-epistemology and the issue of realism The epistemological project as emerging here is a type of proto-epistemology which seeks the conditions of knowledge as such. The basic epistemological relationship subject-object is possible after the stabilization of “the field of inquiry”8 and ignoring the factors which would make them appear. That is why, Taylor points, after Heidegger, to the originality of something as “knower-known complex” in the relation subject-object. Taylor reads: We argue the inadequacy of the epistemological construal, and the necessity of a new conception, from what we show to be the indispensable conditions of there being anything like experience or awareness of the world in the first place just how to characterize this reality, whose conditions we are defining, can itself be a problem, of course. Kant speaks of it simply as “experience”; but Heidegger, with his concern to get beyond subjectivistic formulations, ends up talking about the “clearing” (Lichtung). Where the Kantian expression focuses on the mind of the subject and the conditions of having what we can call experience, the Heideggerian formulation points us toward another facet of the same phenomenon, the fact that anything can appear or come to light at all. This requires that there be a being to whom it appears, or whom it is an object; it requires a knower, in some sense. But the Lichtung formulation focuses us on the fact (which we are meant to conic to perceive as astonishing) that the knower-known complex is at all, rather than taking the knower for granted as “subject” and examining what makes it possible to have any knowledge or experience of a world.9 Hermeneutic proto-epistemology, although trying to reach beyond the clearly epistemological spectrum and investigates into the ontical structure of human cognition, may be treated as a sort of science exposing prejudices and pre-understandings that make cognition unreal. The humanities as proto-epistemology offers two versions: transcendental and hermeneutic. (1) The transcendental version10 presupposes the prerequisites or predispositions needed for cognition to be achievable. The subject establishing another is itself established. Similarly, 8 R. Rorty, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, Princeton University Press, Princeton 1979, p. 352. Overcoming Epistemology, (in:) Philosophical Arguments, Harvard University Press 1995, p. 6. 10 Cf. Andrzej Bronk, Epistemologiczny charakter filozofii Gadamera, “Studia Filozoficzne”, 1985(1). 9 one can ask a question of the possibility for a mind to understand itself. To what an extent can the mind describe itself and how far can we define the existence of language as we do so by using it? In Kant’s theory and in phenomenology there is the problem of synthesis done by the human mind and which escapes any attempt of scientific description. According to Jurgen Habermas and Karl-Otto Apel, the conditions for efficient cognition are to be found in certain communicative competence. (2) Hermeneutic proto-epistemology, although following the idea of seeking the conditions of the capacity of knowledge as such, does not trust the possibility of its full explanation. It does not, however, ensue that it automatically follows the path of relativism or antirealism. When Kuhn speaks of the specificity of the humanities, he points to the lack of uniform paradigm and incommensurability of the present discourses. If, then, in line with the phenomenological and hermeneutic approach each cognition is prospective and contextual and one’s everyday being-in-the-world is something most original and constitutes a point of departure of all theoretical activities, then the question is whether one can reach pure reality, things in themselves? According to Dreyfus, popular, original experience coping with the world does not question the independent existence of this world. Even Heidegger (or late Merleau-Ponty) opts for the minimal realism. As worded by Dreyfus, it is visible when he speaks of deworlding11, the perspective in which everyday reference to the world is broken down and when the sense and obviousness of reacting with the world yields to defamiliarisation. According to H. L. Dreyfus, “the universe constrains us, and rewards us with sight only insofar as we conform to its causal structures. But we are so skilled of getting an optimal take on things that, unless there is some disturbance, we overlook the fact that we once had to learn to align ourselves with the constraints of nature in order to perceive. In general, the universe solicits us to get a better and better grip on its causal structure, and rewards us with more and more successful coping”12 It is of significance to stress that Taylor, or Dreyfus (most probably also Heidegger), speaks of preconceptual way of being in the world, and about non-conceptual coping. Walking and drinking water is possible thanks to pavements and glasses, yet our actions do not have to directly rely on beliefs and propositional knowledge13. 11 H. L. Dreyfus and C. Spinoza, Coping with Things-in-Themselves: A Practice-Based Phenomenological Basis of Realism, in: Heidegger Reexamined. Routledge, London, 2002. 12 H. Dreyfus, Taylor’s (anti-)epistemology, p. 68, in: Charles Taylor, ed. by Ruth Abbey, Cambridge 2005 13 For more, see J. Srzednicki, Norm and Discernment. Study in Metaphysical Logic, vol. A of New Epistemology, Wydz. Filozofii i socjologii UW, Warszawa 2003. Many followers of the hermeneutic theory also subscribe to the opportunity of scientific investigation of reality and do not deny the possibility to know certain causal relationships present in the world. According to Taylor, not only our everyday activity relates to the world but thanks to scientific research there is the possibility of a theoretical grasp of physical reality, which is not accessible on a daily basis, and may correspond to the universe as it is in itself. Taylor assumes that science with its view from nowhere may isolate the causal relationships of universal character. At the same time, he points to the limited possibility of this approach and the possibility to grasp equally valuable aspects of nature itself from a culturally different perspective14 (Dreyfus speaks of the pluralist robust realism). Interesting as it may be, similar opinion can be found in Heidegger: “What is represented by physics is indeed nature itself, but undeniably it is only nature as the object-area, whose objectness is first defined and determined through the refining that is characteristic of physics “15. * * * Hermeneutic universalism aims to diminish the contrast between natural sciences and the humanities, or to question the possibility to develop new version of methodological independence of the humanities. The independence and specificity of the humanities is stressed by the followers of double hermeneutics, i.e. Giddens, Habermas, or Taylor; they subscribe to the idea that the human being is basically a self-interpreting being. Therefore human sciences must pursue radical reflexivity, which is not present when dealing with nature. Yet, some researchers challenge the possibility to set clear borders between these research areas where self-understanding of the human subject does take place and those where is does not. Taylor seems (dogmatically) to assume the existence of infinite knowledge of the structure of human being. Still the knowledge of nature has dramatic impact on the way one acts and the questions one asks about existence. As mentioned elsewhere, the research in natural sciences is an unavoidable background to the work of a specialist in the humanities. Therefore, Ginev, 14 Taylor, as an example, speaks of the Aztec way of seeing things and acupuncture as an efficient way of curing diseases originating from Eastern medicine. 15 Martin Heidegger, ‘Science and Reflection’, The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays, translated by William Lovitt, Harper & Row, New York 1977, p. 173-4. a researcher of hermeneutic approach in natural sciences proposes a continuum theory and points to the “spectrum of theoretical modes of Being-in-the-world that lies between the poles of ‘radical nomological objectification’ and ‘universalizing hermeneutic interpretation.”16 All in all, proto-epistemology as a project proposing the conditions of cognition as such reveals its full dimension in relation to the humanities, for example, theory of literature or cultural anthropology. On the other hand, the interpretation aspect with the notions of preunderstanding, horizon and hermeneutic circle, and the thesis of universal hermeneutics also concerns natural sciences already in the sphere of scientific activity. Proto-epistemology does not challenge the reliability and efficiency of these sciences. Still, it unveils their practical and linguistic traps. There is involved epistemology and antifoundationalistic epistemology, so different in its objectives that, after Charles Taylor, can be named “anti-epistemology”. 16 D. Ginev, A Passage to the Hermeneutic Philosophy of Science, Rodopi, Amsterdam/Atlanta 1997 (Poznan Studies in the Philosophy of the Sciences and Humanities vol. 53), p. 16.