Public Policy Discourse on Peace

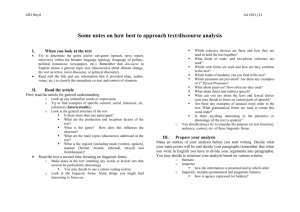

advertisement

One PUBLIC POLICY DISCOURSE ON PEACE William C. Gay 1. Discourse on Peace in Public Policy Forum Can peace be an issue for public policy? For democratic societies, this question may seem rhetorical, since contemporary democratic states stipulate that citizens, or at least their representatives, give consent before war is waged. As far back as 1795, Immanuel Kant contended that whenever the consent of citizens is not necessary for waging war, genuine peace is not possible and, for this reason, supported constitutional, representational government. i However, because debate on whether to wage war is an issue for public policy in a constitutional, representative government does not mean that discussion of whether to pursue genuine peace will be an issue for public policy. Moreover, the structure of public policy discourse may itself thwart pursuit of genuine peace. While I believe that genuine peace, what many call “positive peace,” can be pursued within the public policy forum, I also believe that discourse is generally distorted. Public policy occurs as a specific form of discourse, one forged within the political sphere. Public policy discourse comprises a distinct type of discourse that is governed by specific norms. Some philosophers, building on the work of Ludwig Wittgenstein, see such discourse as a distinct language game.ii Going further, sociolinguist Pierre Bourdieu has shown that discourse is inseparable from the distribution of power in society. iii (This insight is becoming common in treatments of language and politics.iv) In my work, I stress how the dimension of power within discourse is manifest in various forms of linguistic alienation and linguistic violence. v In this chapter, I focus more narrowly on public policy discourse. My thesis is that relations of power, even within democracies, structure public policy discourse in ways that disadvantage peace activists. In the following sections, I discuss three obstacles that must be faced in efforts to infuse the language of positive peace into public policy discourse. First, I address how the pervasiveness of the war myth often rules out serious consideration of peace in the public policy forum. Second, I note ways in which, when peace is addressed in the public policy forum, the language of negative peace is more privileged than the language of positive peace. Third, I comment on problems that delegation causes for peace advocates, namely, ways in which spokespersons for peace groups are frequently linguistically alienated from the public policy establishment and even from their constituents. Finally, I suggest that, despite these obstacles, some encouraging prospects exist for advancing positive peace within the public policy forum. 2 Public Policy Discourse on Peace Before turning to the effects of the war myth, I acknowledge that, despite the importance of advancing peace within discussions of public policy, the primary vehicle for shaping public opinion is the news media. Three main theories of communication show some of the ways in which the news media shape public opinion. (1) Cultivation theory, which investigates factors that shape public beliefs and values, has found that mainstream social values in the United States do not arise from the masses; instead, they are cultivated through repeated exposure to ideologically consistent messages. Exposure to the news media, which is widespread and regular, largely absorbs or overrides differences in perspectives among viewers, creating a homogenized view of the world that downplays more diverse viewpoints. vi (2) Agenda setting, which addresses what the public regards as important and how the public understands the world, has established that most people turn to news sources for their information and that the news that gets covered is controlled by a small, but powerful, group of “gatekeepers.” This research has shown that newspaper editors, station managers, news directors, and individual reporters, themselves products of their culture, nonetheless decide what stories get covered.vii (3) Parasocial interaction, which focuses on how authorities connect to those who rely on them, has shown that authorities enhance their influence when the public regards them as a members of their peer group. In this regard, anchors in broadcast news have this prospect to a much greater degree than public policy analysts.viii Nevertheless, insofar as we are interested in depth and cogency of analysis, the public policy forum provides a more appropriate, if less influential, mechanism for forging informed positions among the public. 2. War Myth and the Language of War Duane Cady coined the term “warism” to refer to the way in which within almost all societies war is taken for granted. ix Connecting Cady’s observations with the treatment of myth developed by Roland Barthes, I characterize warism as a myth that asserts as fact and without explanation that war is natural. In Mythologies, Barthes presents myth as depoliticized speech and asserts: myth does not deny things, on the contrary, its function is to talk about them; simply, it purifies them, it makes them innocent, it gives them a natural and eternal justification, it gives them a clarity which is not that of an explanation but that of a statement of fact. x While the account that Barthes gives is similar to the one provided by Cady, it stresses how myths present phenomena as natural and sever them from their history, specifically from the political forces that shaped this history. When Public Policy Discourse on Peace 3 war is understood as part of our nature, rather than our history, the war myth, in the terms of Barthes, provides us with “the simplicity of essences” and “a blissful clarity” that masks the complexities of our past and alternatives for our future.xi If myth is depoliticized speech, then the priority of the political dimension of human existence needs to be recognized. This point is made explicitly by Ferruccio Rossi-Landi when he says, “No real operation on language can be only linguistic. To operate on language, one has to operate on society. Here as everywhere else, politics comes first.” xii The way in which myths work against recognition of the priority of the political strikes me as the point behind Fredric Jameson’s discussion of the political unconscious. xiii He suggests that, in order to advance social goals, we need to expose the political dimension that so often lies beneath the surface of discourse. This political dimension needs to be retrieved if we are to recognize that the power relations legitimated by, yet masked in, myth can be challenged and political structures that correspond more closely to broadly shared values can be constructed. One of the dangers is that myth can pass as “common sense.” Drawing on the work of Bourdieu, Michel Foucault, and Jürgen Habermas, Norman Fairclough asserts that commonsensical assumptions are ideologies and that language is the form of social behavior in which we most rely on commonsensical or ideological assumptions.xiv Reaching the same conclusion as did V. N. Volosinov much earlier in this century, xv Fairclough contends “the ideological nature of language should be one of the major themes of modern social science.”xvi From his study of language, he concludes that a dominant discourse which largely suppresses dominated discourses ceases to be seen as arbitrary and comes to be regarded as natural and legitimate. He terms this process “the naturalization of a discourse type.”xvii Bourdieu suggests that: any attempt to institute a new division must reckon with the resistance of those who, occupying a dominant position in the spaces thus divided, have an interest in perpetuating a toxic relation to the social world which leads to the acceptance of established divisions as natural or to their symbolic denial through the affirmation of a higher unity . . . . xviii I make these points about myth in order to stress the need to repoliticize public policy discourse, especially when it concerns issues of peace. Since societies generally take war for granted, the assumption of the language of war as natural poses the greatest obstacle to peace. Societies have created a warist discourse that deals abstractly and indirectly with the horrors of war.xix The public who hear or read warist discourse and even the officials who promulgate this discourse may not realize what is really occurring, let alone question whether there might be an alternative. The language of the military establishment, such as the U.S. department of defense, if not also the language 4 Public Policy Discourse on Peace of the diplomatic corps, such as the U.S. department of state, exemplifies the primacy of warist language.xx Endeavors to establish a legitimate discourse about war, to propound an acceptable theory of war, have been ongoing. From Sun Tzu’s The Art of War in ancient China to Carl von Clausewitz’s On War in nineteenth century Europe, the public policy debate has not been on whether war is moral or whether it should be waged, but how to wage war effectively. xxi While the advent of nuclear weapons may have led strategists to pull back from the concept of “total war” in favor of a concept of “limited war,” it has prompted them to make a genuine call for an “end of war.” xxii The language of war moves from the use of euphemisms that mask the horror of war through the use of propaganda that demonizes the enemy and legitimates violence against them.xxiii At the level of euphemism, an aggressive attack by a squadron of airplanes which ordinarily would be called an “air raid” may be referred to as a “routine limited duration protective reaction,” or defoliation of an entire forest may be spoken of as a “resource control program.” A more stark example of euphemism is found when the term “pacification” is used to label actions which involve entering a village, machine-gunning domesticated animals, setting huts on fire, rounding up all the men and shooting those who resist, prodding and otherwise harming the elderly, women, and children. At the next level, the language of war moves from euphemism to propaganda designed to legitimate this violence. For example, in times of war, each nation involved typically presents its adversary as an evil enemy and itself as the embodiment of good. Such distortion of language was used to defend British rule in India, Soviet purges, and the United States’ atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; in these cases, officials resorted to arguments which contradicted the purported aims and values of their governments. Over the last several decades governments and subnational groups have turned to “totalitarian language” in their efforts to “win” the hearts and minds of the masses in support of their political agendas, though, fortunately, such efforts have had only limited success in achieving the goal of thought control.xxiv 3. Language of Negative Peace in Public Policy Discourse I turn to the next challenge for those who wish to influence public policy discourse about peace. The language of peace is an important component in the pursuit of peace and justice. The language of peace, like the condition of peace, can be negative or positive. The challenge posed is well-known to peace activists: contentment with negative peace can thwart pursuit of positive peace. In relation to discourse, the language of negative peace is generally privileged within public policy discussions. In commenting on the distinction between the language of negative peace and the language of positive peace, I Public Policy Discourse on Peace 5 focus on how the structures and rules of public policy discourse provide greater linguistic capital to speakers of the language of negative peace, but I also address the requirements for a language of positive peace. The elimination of the language of war may do little to advance the cause of peace. For example, a government and its media may cease referring to a particular nation as “the enemy” or “the devil,” but private and even public attitudes may continue to foster the same, though now unspoken, prejudice. Just as legal or social sanctions against hate speech may be needed to stop linguistic attacks in the public arena in order to stop current armed conflict, there may be a need for an official peace treaty and a cessation in hostile name calling directed against an adversary of the state. Just as arms that have been laid down can readily be taken up again, even so those who bit their tongues to comply with the demands of political correctness are often ready to lash out vitriolic epithets when these constraints are removed. In the language of negative peace, the absence of verbal assaults about “the enemy” merely masks the lull in reliance on warist discourse. xxv Often, members of the public take idealistic stands that lack solid grounding in a factual understanding of security issues. Consequently, many professionals within the public policy establishment grant rather limited value to public opinion. Robert Bell observes that while those who have spent their lives mastering the various policy alternatives are more sophisticated, policy makers “have to reckon with the limited rationality of public discussion.” xxvi The issue, for him, is how to respond to a public that may not be “receptive to rational policy analysis.”xxvii To assume that public policy professionals are more rational, just because they are better informed, is fallacious. Bell reveals how public values are often of peripheral importance to those charged with implementing policies: OMB is in the business of reexamining and reformulating the purposes of government programs. It is the duty of OMB examiners to refuse to take public formulations of needs as given. OMB instead strains toward policy principles that are more abstract than the needs felt by special interests . . . . To perform these functions, OMB of course makes use of public finance theory, which, in turn, actively resists the way issues are ordinarily discussed in public and substitutes a disciplined approach characteristic of a particular professional group.xxviii In his essay “Public and Private Choice,” R. Paul Churchill makes several points that are relevant to this discussion. He argues for an approach to public policy that takes into account “public choices that represent the expression of social values which play a central role in the definition, by people, of their community or society, and in the formation of their collective purposes and conceptions of meaningful life.” xxix Churchill argues that the effort to “maximize the preference-satisfaction of individuals,” and I would 6 Public Policy Discourse on Peace add the aim to follow the “rational policy analysis” of bureaucratic experts, inappropriately relegates the consideration of values to the private sphere. Churchill concludes that in order for public policy to formulate and debate social values, “we need to develop what Jürgen Habermas called our ‘communicative-moral rationality’ and to remember that the ‘instrumental rationality’ of policy analysis is only the means by which to attain the ends we ought to seek.”xxx From the perspective of Mohandas K. Gandhi, much public policy discourse, in searching for an efficient means, quickly reduces itself to the type of instrumental rationality criticized by Churchill. xxxi The nature of the language of negative peace becomes clear when, within social movements facing frustration in the pursuit of their political goals, a division occurs between those ready to abandon nonviolence and those resolute in their commitment to it. Such a commitment to nonviolence is manifested in the discourse and not just the actions of nonviolentists, such as, Martin Luther King, Jr., Vaclav Havel, and Nelson Mandela. The language of positive peace facilitates and reflects the move from a lull in the occurrence of violence to its replacement with justice. Since the language of negative peace perpetuates structural injustice, establishment of the language of positive peace requires a transformation of cultures oriented to war. The language of positive peace has a variety of correlative nonviolent actions by means of which to continue politics nonviolently––by more intensive means of diplomacy, rather than turning to war, which Clausewitz defined as the pursuit of “politics by other means.” Peace making and its discourse are a continuation of politics by the same means. xxxii I return to some of these points about the language of positive peace in my conclusion. 4. Delegation and Linguistic Alienation The third and less well-known challenge for those who wish to influence public policy discourse about peace concerns problems associated with delegation. For a peace movement to have public policy sway, it must put forward spokespersons who will face dual linguistic alienation. xxxiii They must contend with linguistic alienation from the terminology of the public policy establishment, they face the prospect of linguistic alienation of their constituents in the process of delegation. Bourdieu has analyzed the problems involved in bringing alternative social values to public attention. In order to challenge the dominant discourse, a social group needs to be heard. Their messages may be understood, but that is not the point. Their messages need legitimacy. For a message to have authority, it needs to be spoken or written by someone with authority, someone with a title who represents a constituency. A representative or delegate is needed. As Bourdieu says, “Individuals . . . cannot constitute themselves (or Public Policy Discourse on Peace 7 be constituted) as a group, that is as a force capable of making itself heard . . . unless they dispossess themselves in favor of a spokesperson.” xxxiv Although the group puts forth the delegate to represent its interests, the delegate, by representing the group, gives the group a status that it previously did not possess. Imagine a mob at the doors of government, clamoring for an audience. The “natural” question is “Who speaks for you?” The delegate, not the social group, enters the halls of government. The delegate has voice but is literally separated from the group. Real alienation is only about to begin. The spokesperson, as an outsider to the public policy sphere, experiences linguistic alienation. This linguistic alienation goes beyond a fundamental difference in values. Although the spokesperson speaks the same language, some terms have different meanings and many terms are completely outside the prior, non-technical lexicon of the spokesperson. Until the spokesperson becomes fluent in the “linguistic coin of the realm,” namely, the technical terminology in vogue among the public policy elite, the spokesperson’s effectiveness on behalf of the group is limited. In speaking the official or dominant discourse, part of the message of the delegate is coopted. In learning the technical terminology of the public policy establishment, the spokesperson overcomes linguistic alienation from this type of discourse only to face the prospect of linguistic alienation from the people the spokesperson is trying to represent. Progress made within official circles is hard to “translate” back into the vernacular of the social group being represented.xxxv The delegate can begin to sound even more like a member of the establishment. As Bourdieu observes, “Usurpation already exists potentially in delegation.”xxxvi Delegates can conflate what is good for them with what is good for the group. At this point, the delegate has succumbed to the power of delegation. The delegate may be able to perform various feats of “social magic” that bring status and resources to the group, but the delegate may have become as much, if not more, a functionary of the apparatus as a genuine representative of the group. A distinction can be made between spokespersons who arise from the ranks of grassroots movements and representatives from the ranks of experts within the establishment who “go over” to the side of the people. In recent times many of the leading anti-nuclear activists formerly held governmental, military, or civilian positions in which they worked as nuclear planners. This group of highly trained and formerly powerful individuals represents a very small minority among the voices who speak with technical proficiency about nuclear issues. The vast majority of “experts” remain pro-nuclear. The few who have “defected” to the side of the people, such as many of the members of the Union of Concerned Scientists, have not been alienated from the technical jargon of the nuclear establishment, but they have not escaped the dangers that face the “outsiders” from the ranks of grassroots movements who become spokespersons for their groups. For both defectors 8 Public Policy Discourse on Peace and outsiders, the basic task remains of trying to decipher and demystify the codes of warist discourse for the average citizen. In this move to the general citizenry, both groups of spokespersons face the prospect that their discourse, if it remains too technical, will continue to cause linguistic alienation. A look needs to be taken at the delegates of a social group and at the name of the social group that a delegate represents. Bourdieu observes: The name of groups, especially professional groups, records a particular state of struggles and negotiations over the official designations and the material and symbolic advantages associated with them . . . . The professional name . . . is a distinctive mark . . . which takes its value from its position in a hierarchically organized system of titles. xxxvii Just as a delegate brings a social group to life, the group comes into existence by a name that situates it politically and historically in relation to other groups. Its significance is much like that of a linguistic sign, determined by others in relation to which it stands in opposition. Changes in names of peace groups, perhaps much more than changes in their delegates, mark historical stages in their quest for legitimacy and influence. While these issues surrounding delegation cannot be eliminated, recognition of them can mitigate against the adverse effects of linguistic alienation and possibly can significantly reduce the prospects for usurpation. In order for peace groups to advance their goals, they have no other choice but to face these risks. As Bourdieu notes, “One must always risk political alienation in order to escape from political alienation.”xxxviii 5. Public Policy Discourse Fostering Positive Peace The fact that words and language games, even forms of life, are conventional means a natural basis exists for their maintenance does not exist. New conventions can be adopted. From individual words to entire forms of life, we can make changes which serve broader and loftier interests than current conventions. A peace movement can make an important contribution toward the shifting of public policy discourse toward social values that denaturalize the war myth and repoliticize the quest for peace and justice. In Peace Politics, Paul Joseph observes: Peace Movements are expressions of hope. People give their time, money, talent, and energy against what appear to be overwhelming odds. By almost any measure, the resources of a peace movement are far less than the political, economic, and symbolic assets possessed by the national government. And yet a vision of peace remains. Governments cloak themselves in national glory, national duty, and the national interest. Citizens are sometimes swayed by these appeals. But many are Public Policy Discourse on Peace 9 also moved by the images of children sacrificed for no apparent gain, economic destruction for no possible good, and the perpetuation of international violence as a totally illegitimate method to solve problems.xxxix Joseph stresses that a peace movement should not be judged by narrow criteria of whether it was successful in the legislative initiatives it sought to stop and the ones it sought to pass. If the scorecard were based on such criteria, many peace movements would have to be judged as not being successful. In a more general way, Joseph notes that the peace movement in the peace movement in the United States contributed to ending the cold war. xl Maybe a peace movement may make its greatest contributions to change in other forums than that of public policy per se. It may be its passionate proclamations, its massive marches, and its peaceful protests that attract the attention of the media gatekeepers. These efforts play a role in shaping the social values that inform public policy. In challenging dominant discourse, social groups are engaged in what Bourdieu terms “heretical subversion.” By linguistically challenging the established order, heretical discourse seizes on “the possibility of changing the social world by changing the representation of this world.” xli The practice of heretical subversion is similar to what Richard Rorty means by abnormal or edifying discourse.xlii Heretical subversion exposes the system of representations as non-natural, arbitrary conventions like Foucault’s epistemes and is able to “contribute practically to the reality of what it announces by the fact of uttering it . . . of making it conceivable and above all credible.”xliii According to Bourdieu, when social groups engage in heretical subversion in an informed manner, they can find: in the knowledge of the probable, not an incitement to fatalistic resignation or irresponsible utopianism, but the foundations for a rejection of the probable based on the scientific mastery of the laws of production governing the eventuality rejected.xliv In simpler terms, Bourdieu suggests that we need not give into “fatalistic resignation;” linguistic change that can further the cause of positive peace is not an “irresponsible utopianism.” Many times the first step in reducing linguistic violence is to refrain from the use of offensive and oppressive terms. Just because linguistic violence is not being used, a genuinely pacific discourse is not necessarily present. The pacific discourse that is analogous to negative peace can perpetuate injustice.xlv For instance, broadcasters in local and national news may altogether avoid using terms like “dyke” or “fag” or even “homosexual,” but they and their audiences can remain homophobic even when the language of lesbian and gay pride is used in broadcasting and other public forums. 10 Public Policy Discourse on Peace Governmental officials may cease referring to a rival nation as “a rogue state,” but public and private attitudes may continue to foster prejudice toward this nation and its inhabitants. When prejudices remain unspoken, at least in public forums, their detection and eradication are made even more difficult. The merely public or merely formal repression of language and behavior that express these attitudes builds up pressure that can erupt in subsequent outbursts of linguistic violence and physical violence. The language of positive peace facilitates and reflects the move from a lull in the occurrence of violence to its negation. The establishment of a language of positive peace requires a transformation of cultures oriented to war. The discourse of positive peace, to be successful, must include a genuine affirmation of diversity both domestically and internationally. The effort to establish the language of positive peace requires the creation of a critical vernacular, a language of empowerment that is inclusive of and understood by the vast array of citizens. Several attempts have been made to spread the use of nonviolent discourse throughout the culture.xlvi The Quakers’ “Alternatives to Violence” project teaches linguistic tactics that facilitate the nonviolent resolution of conflict. Following initial endeavors at teaching these skills to prisoners, this project has been extended to other areas. Related practices are found in peer mediation and approaches to therapy which instruct participants in nonviolent conflict strategies. Educational institutions are giving increased attention to Gandhi in order to convey nonviolent tactics as an alternative to reliance on the language and techniques of the military and to multiculturalism as a means of promoting an appreciation of diversity that diminishes the language and practice of bigotry and ethnocentrism. At an international level, UNESCO’s “Culture of Peace” project seeks to compile information on peaceful cultures. Even though most of these cultures are pre-industrial, their practices illustrate conditions that promote peaceful conflict resolution. This project, which initially assisted war-torn countries in the effort to rebuild (or build) a civic culture, can be applied more broadly. The language of positive peace is quite compatible with the democratic spirit and is diametrically opposed to authoritarian traditions. Since the language of positive peace resists monologue and encourages dialogue, it fosters an approach to public policy debate that is receptive rather than aggressive and meditative rather than calculative. The language of positive peace is not passive in the sense of avoiding engagement; it is pacific in the sense of seeking to actively build lasting peace and justice. In this sense, while the language and practice of positive peace facilitates the continuation of politics rather than its abandonment, it also elevates diplomacy to an aim for cooperation and consensus rather than competition and compromise. The language of positive peace provides a way of perceiving and communicating that frees us to the diversity and open-endedness of life rather than the sameness and finality of death that results when diplomacy fails and war Public Policy Discourse on Peace 11 ensues. The language of positive peace, by providing an alternative to the language of war and the language of negative peace, can introduce into public policy discourse shared social values that express the goals of a fully politicized and enfranchised humanity. NOTES 1. Immanuel Kant, Perpetual Peace and Other Essays, trans. Ted Humphrey (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1983), p. 113. 2. Ferruccio Rossi-Landi, “Wittgenstein: Old and New,” Semiotics Unfolding, ed. Tasso Borbé (Berlin: Mouton, 1984), vol. 1, pp. 327–344; Ranjit Chatterjee, “Rossi-Landi’s Wittgenstein: ‘A Philosopher’s Meaning Is His Use in the Culture,’” Semiotica, 84:3/4 (1991), pp. 275–283; and William C. Gay, “From Wittgenstein to Applied Philosophy,” The International Journal of Applied Philosophy, 9:1 (Summer/Fall 1994), pp. 15–20. 3. Pierre Bourdieu, Language and Symbolic Power, ed. John B. Thompson, trans. Gino Raymond and Matthew Adamson (Cambridge. Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1991). See also William C. Gay, “Bourdieu and the Social Conditions of Wittgensteinian Language Games,” The International Journal of Applied Philosophy, 11:1 (Summer/Fall 1996), pp. 15–21. 4. See Fred R. Dallmayr, Language and Politics; Why Does Language Matter to Political Philosophy? (Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1984); Language and Power, ed. Cheris Kramarae, Muriel Schulz, and William M. O’Barr (Beverly Hills. Calif.: Sage Publications, Inc., 1984); Michael J. Shapiro, Language and Politics (New York: New York University Press, 1984); and John B. Thompson, Studies in the Theory of Ideology (Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1984). 5. See William C. Gay, “Exposing and Overcoming Linguistic Alienation and Linguistic Violence,” Philosophy and Social Criticism, 23:2/3 (Spring 1998), pp. 137–156; and William C. Gay, “Linguistic Violence,” Institutional Violence, ed. Robert Litke and Deane Curtin (Amsterdam: Editions Rodopi B.V., 1999), pp. 15–34. 6. George Gerbner, Larry Gross, Michael Morgan, and Nancy Signorelli, “Growing Up with Television: The Cultivation Perspective,” Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research, ed. Jennings Bryan and Dolf Zillmann (Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., 1994), p. 27. 7. Maxwell McCombs, “News Influence on Our Pictures of the World,” Media Effects, ed. Bryan and Zillmann, pp. 12– 13. 8. Dominick A. Infante, Andrew S. Rancer, and Deanna F. Womack, Building Communication Theory (Prospect Heights, Ill.: Waveland Press, 3rd ed., 1997), pp. 370–372. 9. Duane Cady, From Warism to Pacifism: A Moral Continuum (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989), pp. 3–19. 10. Roland Barthes, Mythologies, ed. and trans. Annette Lavers (New York: Hill and Wang, 1972), p. 143. 11. Ibid. 12. Ferruccio Rossi-Landi, “Ideas for the Study of Linguistic Alienation,” Social Praxis, 3:1/2 (1975), p. 90. 13. Fredric Jameson, The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1981), esp. pp. 17–20, 283–284. 14. Norman Fairclough, Language and Power (London: Longman Books, 1989), p. 2. 15. V. N. Volosinov, Marxism and the Philosophy of Language, trans. Ladislav Matejka and I. R. Titunik (New York: Seminar Press, 1973). 16. Fairclough, Language and Power, p.3. 17. Ibid., p. 91. 18. Bourdieu, Language and Symbolic Power, p. 128. 19. See William C. Gay, “The Language of War and Peace,” Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace, and Conflict, ed. Lester Kurtz (San Diego, Calif.: Academic Press, 1999), vol. 2, pp. 303–312. 20. See William C. Gay, “Star Wars and the Language of Defense,” in Just War, Nonviolence, and Nuclear Deterrence: Philosophers on War and Peace, ed, Duane Cady and Richard Werner (Wakefield, N.H.: Longwood Academic Press, 1991), pp. 245–264. 21. Sun Tzu, The Art of War, trans. Samuel B. Griffith (London: Oxford University Press, 1963); and Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1976). 22. See William C. Gay and Michael Pearson, The Nuclear Arms Race (Chicago: The American Library Association, 1987), pp. 70–71, 163–164. 23. Gay, “The Language of War and Peace,” pp. 307–309. 24. See John Wesley Young, Totalitarian Language: Orwell’s Newspeak and Its Nazi and Communist Antecedents (Charlottesville, Vir.: University Press of Virginia, 1991). 25. See William C. Gay, “Nonsexist Public Discourse and Negative Peace: The Injustice of Merely Formal Transformation,” The Acorn: Journal of the Gandhi-King Society, 9:1 (Spring 1997), pp. 45–53. 26. Robert Bell, The Culture of Policy Deliberations (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1985), p. 114. 27. Ibid. 28. Ibid., p. 122. 29. R. Paul Churchill, “Public and Private Choice: A Philosophical Analysis,” The Moral Dimensions of Public Policy Choice: Beyond the Market Paradigm, ed. John Martin Gillroy and Maurice Wade (Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992), p. 341. 30. Ibid., p. 350–351. Public Policy Discourse on Peace 13 31. H. J. Horsburgh, “The Distinctiveness of Satyagraha,” Philosophy East and West, 19:2 (April 1969), pp. 171–80. 32. See William C. Gay, “The Prospect for a Nonviolent Model of National Security,” On the Eve of the 21st Century: Perspectives of Russian and American Philosophers, ed. William Gay and T. A. Alekseeva (Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, Inc., 1994), pp. 119–134. 33. See William C. Gay, “Nuclear Discourse and Linguistic Alienation,” Journal of Social Philosophy, 18:2 (Summer 1987), pp. 42–49. 34. Bourdieu, Language and Symbolic Power, p. 204. 35. See Henry A. Giroux and Peter McLaren, “Teacher Education as a Counterpublic Sphere,” Philosophy and Social Criticism, 12 (1987), pp. 51–69. 36. Bourdieu, Language and Symbolic Power, p. 209. 37. Ibid., p. 240. 38. Ibid., p. 204. 39. Paul Joseph, Peace Politics: The United States between the Old and New World Orders (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993), p. 140. 40. Ibid. 41. Bourdieu, Language and Symbolic Power, p. 128. 42. Richard Rorty, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1979), esp. pp. 360, 365–366. 43. Bourdieu, Language and Symbolic Power, p. 128. 44. Ibid., p. 136. 45. William C. Gay, “The Practice of Linguistic Nonviolence,” Peace Review, 10:4 (1998), pp. 545–546. 46. Gay, “The Language of War and Peace,” p. 311.