JewishLiFElanguage_the hebrew vowels

advertisement

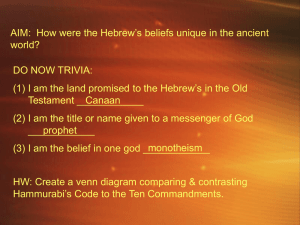

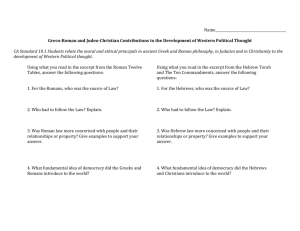

JewishLiFElanguage The Hebrew Vowels That Changed the World by Joel M. Hoffman Roughly 3,000 years ago, in and around the area now known as Israel, a group of people who may have called themselves Hebrews (Ivrim) or Israelites began an experiment in writing that would change the world. Four means of written communication preceded the Israelites’ innovation. The very first writing system used by humans was barely a system at all. Some 6,000 years ago, animal traders drew pictures of their animals and probably added marks next to them to indicate quantity. So a merchant who wanted to tell his business partner to expect five sheep could draw a sheep along with five marks on a tablet and have it sent on to his partner, rather than meet him face to face or rely on the accuracy of a personal go-between. While this system represented an enormous leap forward, its message options were nonetheless severely limited. The second system, used with great success by the Egyptians, introduced hundreds or thousands of “icons,” symbolic representations of the meaning of words. For example, a circle around a smaller circle represented “sun.” The system grew in complexity to include icons for abstract nouns, verbs, etc., allowing for the creation and transmission of more complex messages. Still, literacy remained limited to the professional class of readers and writers known as scribes. The third way of writing words dates to the third millennium B.C.E., when the Sumerians devised a system to record the sounds rather than the meanings of words. They created a few hundred symbols, one for each syllable of their language, and combined them to represent words. This syllabic system required fewer symbols than the Egyptians’ meaning-based one, but even so, its complexity and the great number of symbols put it beyond the reach of most people. Written communication was still limited to scribes. The Consonants Sometime during the second millennium B.C.E. a fourth system arose. A language commonly called “proto-Canaanite”—that is, “the language that would become the languages of Canaan,” including Moabite, Phoenician, Hebrew, etc.—began to be written entirely in consonants. For example, the common ancient Canaanite word ram, meaning “high/exalted,” was written as RM; the word for “god,” el, was spelled with the Hebrew letter aleph followed by L; and its plural, “gods” (elim), was written with the Hebrew letter aleph followed by LM. Anyone could learn to write using this system because it consisted of about two dozen symbols. In various combinations, they could spell any word in the language. The problem, however, was that, without vowels, many people couldn’t read what they had written. For example, while the word RM represented ram, it could also be rama (height). The Vowels Enter the Hebrews. In roughly 1000 B.C.E., around the time of King David, the Hebrews made a seemingly minor improvement to the Phoenician consonantal system. (The Phoenicians probably lived in what is now southern Lebanon and northern Israel.) They doubled up some letters, using them not only as consonants, but also as vowels. The letter H (which we call a heh), for example, represented both a consonant and also the vowel A; the letter Y (yud) also represented the vowels I and E; and the letter W (now called vav, though back then it probably had a W rather than a V sound) also represented the vowels O and U. By using letters for both consonants and vowels, the Hebrews created the alphabet. (What we now call the “Hebrew vowels”—the dots and dashes in and around the letters—are a more recent invention, dating back only about 1,100 years.) Spelling in antiquity was often a matter of personal opinion, and in ancient Israel the vowel-letters were generally optional. The word for “high” (ram) was still written RM; a writer who wanted to specify rama could append a heh in its newly invented role as vowel: RMH. The system wasn’t perfect, but, for the first time, it enabled the average person to learn how to read and write. The Israelite people could thereby observe the exhortation in Deuteronomy 6:9 to “write them [these words] on the doorposts of your house, and upon your gates.” In the Bible, these special vowel-letters were used symbolically as well as phonetically. Genesis, for example, relates the story of Abram (aleph-bet-resh-mem), a name that simply means “exalted father” or, more loosely, “tribal elder.” When he becomes an Israelite, a heh is added inside his name to form Abraham (aleph-bet-resh-heh-mem). Sarai similarly becomes Sarah. More impressively, a heh is added to the common word elim (“god”) to form elohim. The patriarch, matriarch, and deity of the Israelites got their names from the insertion of a heh into an otherwise ordinary word. Even more remarkably, the four-letter name of God (or “tetragrammaton,” a word that comes from the Greek for “four-lettered”) consists entirely of the vowel-letters: yud-hehvav-heh. Rather than its pronunciation having been forgotten, as some traditions hold, most likely it never had a pronunciation. It was probably a purely symbolic use of Israelite vowel “technology.” Hebrew Begets Greek & Latin The alphabet spread widely and quickly. The Greeks copied it (or an Aramaicized version of it), using alpha for aleph, beta for bet, gamma for gimel, and so forth. Then the Romans copied the Greeks, giving us A, B, C.... A variation of the Greek alphabet called Cyrillic came to be used for Russian, Serbian, and other Eastern European languages. Variations of the Latin took hold among the major languages of Western Europe and of the Americas. Additionally, the Hebrew alphabet spawned Arabic writing (used for Arabic, Persian, and some others), and Brahmi, which in turn would become Devanagari, used for Hindi and other major languages of the Indian subcontinent. With the notable exception of Korean, almost all the alphabets in the world today—whether in Jerusalem, New York, Moscow, London, Riyadh, Buenos Aires, or Mumbai—are rooted in a 3,000-year-old Hebrew experiment. So the next time you read the Torah, a Hebrew prayer, or even just this magazine, thank an ancient vowel. N Dr. Joel M. Hoffman teaches at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in New York; serves as resident scholar at Temple Shaaray Tefila in Bedford Corners, New York; and is the author of In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language. The evolution of writing: 1) The very first writing system: Animal traders drew pictures of their animals, adding marks to indicate quantity, c. 5th century BCE. 2) The Egyptians introduced “icons” such as the hieroglyphics shown here, from the Tomb of Seti I, 13th century BCE. 3) The Sumerians devised a system to record the sounds rather than the meaning of words, as shown here in a clay tablet from Jamdat Nasr in Iraq (circles and half circles indicate numerals), c. 4th century BCE. 4) Phoenician writing, as engraved in this votive plaque at Tal Silg, Malta from the 3rd century BCE, was written entirely in consonants. 5) The Hebrews added vowels to the Phoenician consonantal system, as shown in this 1st century BCE parchment from the Habbakuk Bible Commentary (part of the Dead Sea Scrolls). 6) Author’s chart. #2: The Bridgeman Art Library; #3: Bridgeman Art Library/Ashmolean Museum, U. of oxford, UK. #4:Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY; #5: Bridgeman Art Library; #6: © 2007 Joel M. Hoffman. Used with permission. Evolution of the Aleph Bet Hebrew 9th century BCE Greek 6th century BCE Greek 4th century BCE Hebrew 2th century BCE Hebrew Modern (printed) English Modern (printed) learn hebrew |on your own Rabbi Aaron Starr’s A Taste of Hebrew teaches the Hebrew alphabet as well as interesting tidbits about the letters and prayers. Readers can then move on to the rest of the Hebrew for Adults series. URJ Press, 888-489-8242, www.URJBooksandMusic.com.