Leisure Travel and the Internet

advertisement

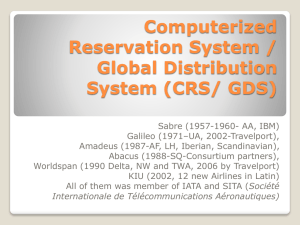

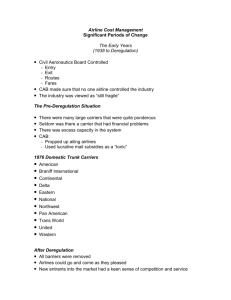

Leisure Travel and the Internet In the Beginning International leisure travel before the Second World War was rather the preserve of the elite class, epitomised by the upper classes' grand tour of Europe, as portrayed in Merchant Ivory film ‘A Room with a View’. Significant technological and infrastructural advances in aviation catalysed by the war efforts enabled a post war tourism boom in American visitors to Europe. (Calder, 2002) Pan Am offered heavily discounted air fares in the newly created economy cabin, enabling ex-servicemen to return with their families to explore the European continent they had helped liberate. The emergence of lower cost and more reliable jet aeroplanes such as the Boeing 707 and the later 747 played an important role in making air travel more accessible on inter-continental routes. Intra-European leisure travel can track its development back to 1950 when Vladimir Raitz founded Horizon with a small office in central London, taking groups on two week all-you-caneat-and-drink trips to Corsica (Calder, 2002). Having overcome significant governmental regulation and monopolistic incumbents, the path eventually cleared for the development of the leisure air travel industry. Tour operators were able to circumvent highly restrictive regulations by avoiding flag carrier operated business and political destinations in favour of seasonal routings predominantly in the Mediterranean basin and by offering inclusive tour (IT) products of accommodation and flights that obscured from travellers the cost of the flight element. These non-scheduled charter operations grew fast, flying densely seated aircraft hard through the summer season, on tight schedules. Long operating days and often with little or no back up contingency capacity led sometimes to long airport delays for holiday makers. These efficiencies helped keep average seat costs low, but impacted customer convenience. Blocks of seats were sold to tour operators who committed to pay for all the seats whether they were sold or not. This practise encouraged last minute deep discounting of perishable stock, with savvy holidaymakers learning to book late for bargain prices and stoking strong price competition in the sector. Contemporary European brand examples would include TUI, Kuoni, Club Med and Grupo Viajes. (Horner and Swarbrooke, 2005) 1 ©McGraw-Hill 2009 Principles and Practice of Marketing 6e David Jobber The Emergence of the High Street Travel Agent In the mid and late twentieth Century the challenge for the leisure air travel industry was how to get the product to the mass market. The complexity of transaction (select, book and pay for a holiday package) often required a face-to-face interaction, best undertaken in a High Street travel shop. The travel agent’s product involved bundling services from a variety of suppliers that may have also included hire car, excursions, tickets, insurance and foreign currency (Horner and Swarbrooke, 2005). Various branded regional and national chains of travel shops emerged, with many smaller local businesses able to set up because of relatively low barriers to entry. A desk, telephone and paper schedule of flights and hotel space was often all that was required by a tenacious entrepreneur with reasonable customer service skills. IATA (International Air Transport Association) accreditation required agents to provide a minimum service level and a significant financial guarantee, which provided a certain level of reassurance to suppliers and travelling customers. A number of high profile tour operator business failures resulted in, sometimes literally, penniless holiday makers being stranded in remote Mediterranean resorts. Scared by the threat of imposed governmental regulation, industry associations such as ABTA (Association of British Travel Agents) facilitated programmes to provide financial guarantees to help support consumer confidence (ABTA.com). Third party agent commissions developed, with scheduled airlines typically paying 9% as standard on international routes and tour operators sharing as much as a quarter of the sale price with their intermediary. Additional incentives, known as overrides or kick back payments, were sometimes paid by airlines to travel agents based on sales performance, perhaps up to 5% on top. Shaw (2004) suggests that profligate, untargeted agent incentivisation of agents gave rise to high levels of airline commission costs. This approach may have helped encourage agents to grow and in many European markets it became typical for a small number of large ‘chains’ to account for large market share, using their size to leverage wider margins and more favourable terms. However, with fewer, large customers controlling distribution (airlines might have sold 10% of their seats via airport ticket desks, travel shops and call centres) some agency chains began to flex their muscles and sought to trade off suppliers against each other, to push up their margins. 2 ©McGraw-Hill 2009 Principles and Practice of Marketing 6e David Jobber From CRS to GDS Airlines, early pioneers in global communications networks, having already developed their own in-house electronic booking systems, identified the need for a computer reservations system (CRS) to link travel agents in real time to pricing and seat availability data. System development costs were significant and while one or two airlines often spearheaded developments they usually sought to share costs and enhance the systems attractiveness by including partner airlines. (Shaw, 2004) Over time two large CRS organisations emerged in USA (SABRE and Worldspan) and two in Europe (Amadeus and Galileo) with a more fragmented national carrier aligned market in Asia. In the three decades after the Second World War the airlines were heavily regulated, resulting in rather limited competition, a contextual consideration that is important to note when appreciating the evolution of travel distribution. Over time the CRS product range extended to include hotels, car hire, train journeys and cruise holidays, enabling travel agents to offer their customers a one-stop shop for all their significant travel needs. Further CRS diversification was delivered via IT consultancy, scheduling and reservation system hosting, in an apparent leverage of a technology capability and an understanding of the aviation industry. (Hanlon, 2007) To reflect this development the organisations became known as Global Distribution Systems (GDS), rather than the more narrow CRS. While diversifying, GDSs also sought to grow their core business by offering agents incentives for increased bookings in return for free computer terminals or cash payments. Charging $3 or more per booking (Doganis, 2001), the big four GDS companies in 2004 took 1.2 billion bookings, splitting market share; Amadeus 33%, Sabre 29%, Galileo 21%, and Worldspan 16%. With little real competition and GDS access a must have for travel agents the big four were able to earn their (predominantly airline) owners handsome returns, pushing charges to airlines up to absorb cost increases. (Hanlon, 2007) Many of the larger legacy carriers were little concerned about paying increased GDS charges as these were offset by profit dividends from their highly profitable GDS businesses. In 2002 Worldspan explicitly recognised an inherent flaw in its business model that saw airlines pay the GDS charge, yet incentivised travel agents to boost transactional volumes, where unscrupulous agents were known to create a variety of bookings (passive, multiple, duplicate, speculative) that would trigger GDS incentives, putting additional costs on the airlines without a related revenue stream. (Holloway, 2003) 3 ©McGraw-Hill 2009 Principles and Practice of Marketing 6e David Jobber Online booking engines developed, some out of GDSs e.g. Travelocity from Sabre and Expedia from Worldspan (with Microsoft) while a number of airlines joined together to create Obitz (USA), Opodo (Europe) and Tabini and Zuji (Asia). (Horner and Swarbrooke, 2005) The auction online player Priceline and late availability specialist Lastminute emerged to provide distribution for excess capacity, a role traditionally taken by bricks and mortar consolidators, who could ensure short notice, volume sales into lower profile price sensitive market segments such as students and diaspora communities. A number of price comparison websites also emerged such as sidestep and kayak who were able to offer comparisons that included low cost carriers, a point of competitive advantage over GDS dependent Travelocity and Expedia. (Holloway, 2003) Distribution technology cost transparency Low cost carrier lead in fares were often considerably lower than those of traditional airlines because they bypassed the GDS network in favour of cheaper call centres (easyJet painted their telephone number on the side of their aircraft) and later by using the web. An IATA study in 2006 showed that distribution costs split: 18% agency commissions, 30% on reservations and ticketing and 7% on GDS fees. GDS charged a flat fee per ticket, resulting in a very high proportion charge on shorter, economy class fares, while on longer and premium cabin fares the cost was negligible. (Hanlon, 2007) It was not purely the development of airline web site booking engines that changed the face of travel distribution, but this had to be partnered with remote payment capability, internet-wide penetration and a significant shift in customer behaviour to feel comfortable making their travel arrangements using a computer. Early experiments offering customers choice in the distribution channel saw rather limited take up of new, costly web developments. Contractual agreements with GDS companies and banks often inhibited the use of pricing differentials (e.g. web only fares), but surcharges of the order £5-£20 were gradually applied to the more expensive human intervention channel choices. Price sensitive customers, particularly those purchasing relatively uncomplicated short-haul trips, quickly became accustomed with the online booking and payment process and low cost carriers were boasting 95% web distribution quite quickly. Traditional carriers, who had more complex contractual arrangements to carefully work through, followed behind. 4 ©McGraw-Hill 2009 Principles and Practice of Marketing 6e David Jobber Payment Historically, airline agent travel intermediaries were able to pass on the 2-5% credit card commission cost and risk from fraud to the airlines, who had often signed deals with the credit card companies that did not permit them to discriminate pricing according to payment method. Thus, travellers had no incentive to use cash or a cheque (with perhaps a 1% cost) rather than 4% average credit and charge cards, which often offered their customers additional individual benefits such as deferred payment, bankruptcy protection and perhaps even travel insurance. (Doganis, 2002) As competition intensified further, more focus was put on the cost of payment and particularly credit card charges. The result of changes to long standing agreements saw averaged credit card surcharges routinely applied in a very transparent manner by airlines, which gave consumers visibility of the costs of different payment methods and enabled consumer choice for each transaction. Irish carrier Ryanair, the self-styled lowest cost European airline, took this ‘a la carte’ approach further, introducing drip charges for airport rather than online check-in, and hold luggage. This approach enabled the airline to offer lead-in fares at £9.99, 99p and even ‘free’, a highly attractive promotional approach that simultaneously reinforced a strong value for money image and generated prospective customer hits on ryanair.com. (Creaton, 2004) Disintermediation New entrant low cost carriers (LCC) took the opportunity presented initially by call centres and then by the internet to bypass (or take out the intermediary) travel agent distribution, which represented a high percentage cost on the lower fares they typically charged. (Shaw, 2004) LCCs had to be more dependent on advertising, notably press, to offset the absence of travel agents and to drive customers direct to the airline. (Doganis, 2001) Merrill Lynch calculated in 1999 that it cost US domestic airline America West $23 to sell a ticket through a traditional travel agency, $20 via an online travel agent, $13 from its own call centres and $6 on its own website. (Holloway, 2003) Price sensitive leisure travellers would likely switch carriers for a $17 fare differential, even when this entailed using unknown airline brands, pay for drinks and food on board and travel via less developed airports. Historically, airline customers were presented with the same selling price regardless of differentials in the costs of the distribution, with retail customers often unaware of the commissions being earned by travel agents. The percentage commission approach was brought under scrutiny, perceived to perhaps be too rich 5 ©McGraw-Hill 2009 Principles and Practice of Marketing 6e David Jobber on high fares and insufficient reward for the work involved in selling lower fares. (Doganis, 2002) Agents were increasingly squeezed out of straightforward, low cost travel sales as customers voted with their feet, unwilling to pay the increasingly transparent cost of a travel agent and ever more confident of using internet booking engines. Many LCC’s began to offer from their websites products and services that travel agents used to bundle, such as insurance, accommodation, car hire even ski and boot rental and lift passes, often providing significant commission revenue streams at little cost to the airlines. Conclusion The internet combined with airline industry liberalisation and deregulation has enabled new entrants to innovate air travel distribution, putting competitive pressure on incumbents to revisit their distribution channel strategy, resulting in significant industry-wide, structural change. Providing consumers with the information to appreciate differential channel costs has seen air travellers switch towards lower cost methods, particularly when required to pay more for more expensive choices. Traditional travel agents, who historically enjoyed a major role as intermediaries linking air travel buyers to leisure suppliers, have experienced a significant change in their business, have been forced to make their service for money proposition more transparent and have been squeezed out of simple mass market transactions. Other intermediaries, such as credit card companies and GDSs have also experienced change as more intense market competition forced cost scrutiny on the entire leisure travel distribution model. Questions 1. Why did incumbent airlines not use the threat of GDS and travel agent bypass to drive distribution cost savings earlier ? 2. Are travel agents passé? What useful role might they fill? 6 ©McGraw-Hill 2009 Principles and Practice of Marketing 6e David Jobber Reference List Calder, S. (2002) No frills: The truth behind the low cost revolution in the skies. London: Virgin Books Creaton, S. (2004) Ryanair: How a small Irish airline conquered Europe. London: Aurum Press Doganis, R. (2001) The airline business in the 21st Century, Routledge: Oxford, UK Doganis, R. (2002) Flying off course: The economics of international airlines 3rd Ed. Oxford:Harper Collins Hanlon, P. (2007) Global airlines: competition in a transnational industry, 3rd Ed. ButterworthHeinemann/Elsevier: Netherlands Holloway, S. (2003) Straight and level: practical airline economics, 2nd Ed. Aldershot, Hants, UK: Ashgate Horner, S. and Swarbrooke, J. (2005) Leisure marketing: a global perspective. Oxford: Elsevier Butterworth Heineman Shaw (2004) Airline marketing and management. 5th Ed. UK:Ashgate This case was prepared by Justin O’Brien, Teaching Fellow in the School of Management at Royal Holloway, University of London 7 ©McGraw-Hill 2009 Principles and Practice of Marketing 6e David Jobber